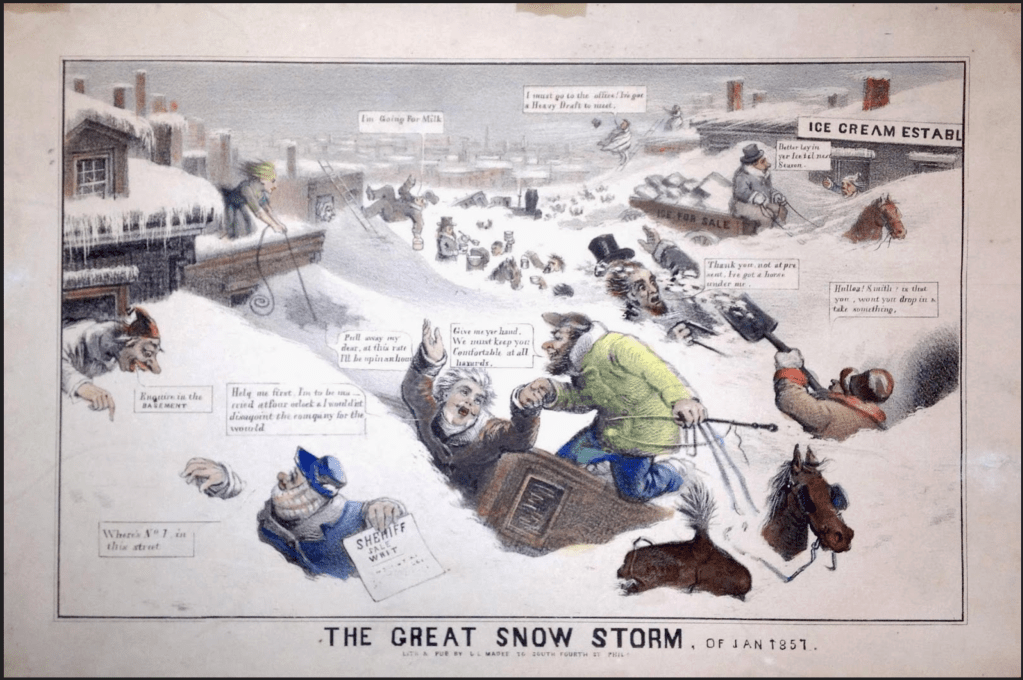

A severe blizzard immobilized the Mid-Atlantic region in January 1857. For multiple days, the storm raged for over twenty-four hours, burying the landscape under a layer of snow that measured nearly fifteen inches on the level and accumulated in drifts reaching ten to fifteen feet. The storm paralyzed the economic infrastructure of the region, rendering the major highways leading from the rural districts of Prince George’s County impassable and forcing the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad to suspend all travel in and out of Washington, D.C.

“a vast sea of snow”: the View from the city

The Snow Storm and its Effects. —The long-wished-for snow storm commenced on Saturday evening last about 6 o’clock. At first it commenced as a mild, insinuating sort of snow, and continued so during the night. The fall through the night, however, must have been pretty full, for at sunrise Sunday morning, the snow was at a dead level of from 10 to 12 inches. To the boys, of a larger or smaller growth, the first appearance of the snow was a cause of much rejoicing and many were expected out at sleighing, but the snow soon disappointed them, as it began to fall very fast about 9 o’clock, and kept them all in their holes. All through Sunday the snow storm continued to rage with great violence, making it impossible to go out. The wind was from the northeast, and came in heavy gusts, appearing like a person twisting the whole of the flakes into a sort of rope, then letting go, when it would unwind and fill the whole atmosphere with a very dense mass of snow.

On Monday morning the face of all nature presented one vast sea of snow, the drifts being from 6 to 10 feet deep, and on a level full of snow to the astonishing depth of some fifteen feet; for in some places the fences were entirely submerged, and the surface of the snow above the ground was some ten feet deep, but in places where the fences were visible the drifts would be found on a level with the top. The various curves the snow assumed in the drifts are singularly graceful and beautiful; on Sunday the wind had, in some places, so curiously carved the exterior of an old fashioned dormer window, that it looked as if a person had been making imitation curtains, and then dropped with a circling sweep that was as graceful as could be conceived. The traveling for some time to come is therefore likely to be confined to the conveyances of nature’s providing.Evening Star, District of Columbia, Jan 19, 1857

“three great highways…blocked up”: the View from the country

We salute our readers this morning from the inside of a Snow-Drift, and wish a happy exit to all of them who may be in a similar plight—as who are not? The Snowing genius commenced operations during Saturday night—and the Blowing genius was not so far behind him, but that be easily overtook him very early Sunday morning.—These two, having at that time to all appearances full possession of things temporal, forthwith set to for the mastery and waged a contest for twenty-four hours excessively disagreeable to all but themselves. The state of the field on Monday morning indicated a drawn fight. It seems that wherever “Blowing” had a clear sweep with his wind batteries he conquered and cleared the ground; but “Snowing” piled up his trophies in all the nooks and corners that were out of range of the guns. “Quiet people” (by which we mean those very respectable citizens who value dry feet more than the pleasure of walking in the snow) will probably give the victory to the wind; and we are sure the sleighers will be forced to the same award, in view of the havoc which the drifts have made in their sport. Neither of the combatants, we are sorry to say, had much respect for the Press, its habitation and mysteries—for an enormous mass was piled against our door and a full sufficiency forced through our windows.

No such snow storm has been seen in these parts for many years. And many years, we trust, will again pass away before the advent of such another. The roads are all blocked up by the drifts, and travel has come to a halt. Three great highways lead into this town. We believe nothing in the shape of a vehicle can travel on either one of them. We are thus cut off from all communication with our friends in the “rural” districts. We have only to hope they are not Glad of it.

The present state of affairs being one of these situations which require time for solution all we can do is to sit down quietly, exercise faith and patience, and look forward with fortitude to a “general thaw and universal happiness.” In this spirit we send forth our paper to its readers, not knowing if it will ever reach them. But if it shall, they will be gratified to know we still hold them in remembrance, and, wishing them a deliverence from the heroes of “Snowing” and “Blowing,” hope it may find them in the comfortable protection of the Genius of Fire.

Planter’s Advocate and Southern Maryland Advertiser, Jan 21, 1857

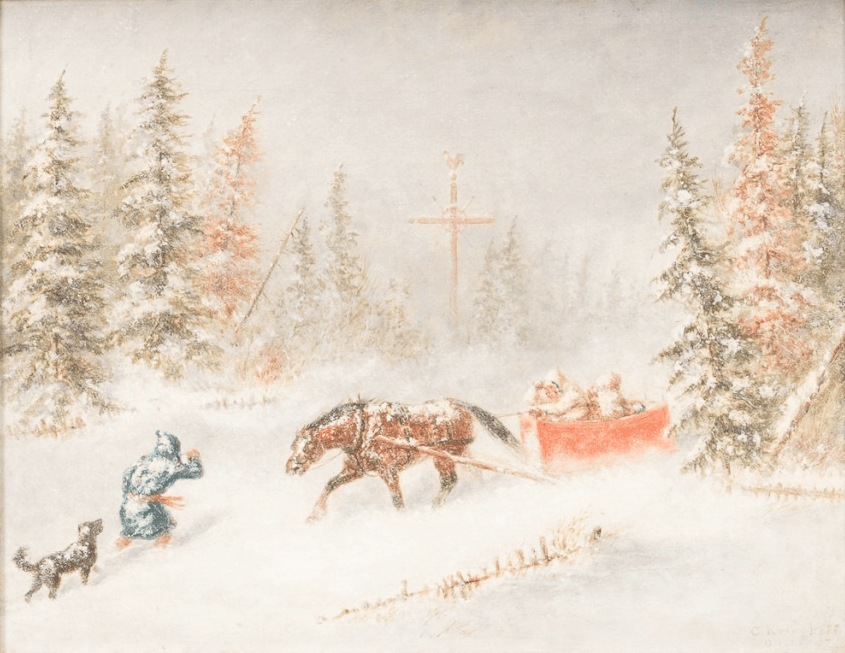

the planter’s View: a “disagreeable” halt to sport and society

The blizzard descended on Prince George’s County, with the editors of the Planters’ Advocate using their time to write a narrative, personifying the snow and the wind, creating a genteel and literary tone as it reports the impact of the storm on the planter class. The author laments the isolation the storm created as he laments “the havoc which the drifts have made in their sport [sleighing]” and how the storm “cut off from all communication with our friends in the ‘rural’ districts”. The author also reflects a class buffered from the most severe consequences of the storm, able to “sit down quietly, exercise faith and patience” and await a thaw in the “comfortable protection of the Genius of Fire.”

the enslaved experience: a struggle for Survival

However, for the enslaved Black population, the storm represented an immediate crisis, intensifying the harsh realities of chattel slavery through the dual threats of extreme exposure and the heightened labor demands required to maintain the comfort and safety of their enslavers.

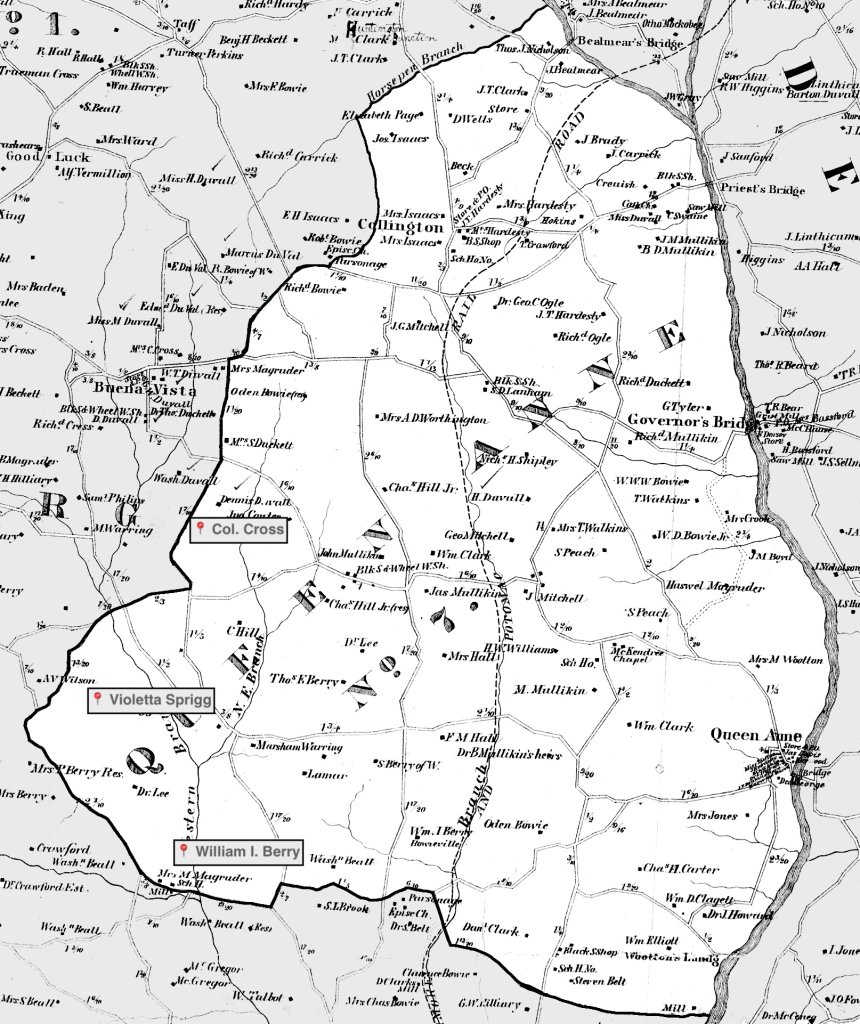

Sad Accident.—We are pained to learn of a melancholy mishap on the farm of William I. Berry, Esq., which resulted in the death of Miss Virginia Clagett, a daughter of Thomas Clagett, Esq., near this village. She was living in the family of Mr. Berry, (a brother-in-law,) and on Sunday afternoon, during the snow-storm, accompanied one of his negro girls to a quarter some distance from the house. It is supposed that while attempting to return at night they were overpowered by the snow and severe cold. Both were found the next morning in the intervening field, having been frozen to death –Planters’ Advocate, Jan 21, 1857

Centering the loss of Berry’s sister-in-law, the article treats the death of the unnamed Black woman as a minor detail, outside of the fact that Clagett was accompanying her on an unnamed task, likely related to the management of the house, as the planter class relied on the labor of enslaved Black people to provide the creature comforts of the house. Their trip, whether for providing food, checking on others, or another compelled reason, placed both individuals in a position of extreme vulnerability, a risk inherent to a plantation’s spatial geography with outbuildings separate from the main dwelling house.

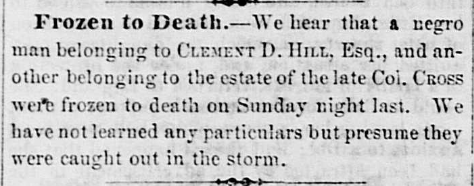

Frozen to Death.—We hear that a negro man belonging to Clement D. Hill, Esq., and another belonging to the estate of the late Col. Cross were frozen to death on Sunday night last. We have not learned any particulars but presume they were caught out in the storm. –Planters’ Advocate, Jan 21, 1857

The brevity of this article speaks to the dehumanizing nature of chattel slavery. The deaths of these two men are noted as events, but they merit no further inquiry or description, reflecting a societal indifference to the specific lives and circumstances of the enslaved.

Frozen to Death.—We regret to learn that Mrs. Violetta Sprigg has lost a valuable negro woman, who, together with one of her men servants, was brought home in a dying condition, having been caught out in the storm of last week. The man was considered in a dangerous condition, as also another woman, who subsequently reached home; and a fourth has been missing for some days, and is supposed to have been buried beneath the snow. –Planters’ Advocate, Jan 28, 1857

Finally, this report, a week after the storm, speaks to the loss of multiple people, yet leads with the language of the marketplace, stating she “has lost a valuable negro woman.” The primary framing is one of economic loss for the enslaver, erasing the humanity of the deceased and reducing her to an asset. This is a stark example of the concept of “external market value” defining a human life. The brevity of the article leaves open two possibilities for the four people caught in the storm. The fact that they were in a group suggests they were performing a task required by the enslaver, or perhaps they formed a familial cohort attempting to reach shelter or aid one another.

economic epilogue: the Thaw and the resumption of Labor

The fine, open weather which has succeeded the terrible storm period, is but little removed from a genuine spring season, and is beginning to create a little out-door activity. Stripping tobacco and preparing tobacco-beds are tasks now engaging the attention of the farming community very generally. The roads are improving. –Planters’ Advocate, Feb 18, 1857

The post-storm period saw the area thawing with the enslaved Black individuals who survived the storm forced to engage in the perennial tasks of an agricultural economy dedicated to the production of tobacco. After enduring the life-threatening conditions of the blizzard in inadequate housing and clothing, the enslaved survivors were immediately forced back into the strenuous, labor-intensive cycle that produced the wealth of the “farming community.” “The roads are improving” marks the end of the planters’ isolation and the full restoration of the transportation network essential for commerce and the enslavers’ social control.

The Great Blizzard of 1857 revealed the brutal inequities of the antebellum Chesapeake. While the region’s planters and editors chronicled the disruption to their commerce and social routines, their accounts inadvertently document a world buffered by the forced labor that sustained their comfort. For the enslaved Black population, however, the storm was a lethal reality. The brief, dispassionate newspaper accounts of their deaths—lamented as the loss of “valuable” property, noted as afterthoughts to the deaths of enslavers’ kin, or dismissed without “any particulars”—provide chilling direct evidence of a system that commodified human life. Ultimately, the unnamed men and women who perished in the snow were casualties not only of the blizzard but of the institution of chattel slavery itself, which enforced their vulnerability and then recorded their deaths with the same cold calculus used to value property.