What connection if any does James Stewart have to the enslaved of Notley Young of Prince George’s County?

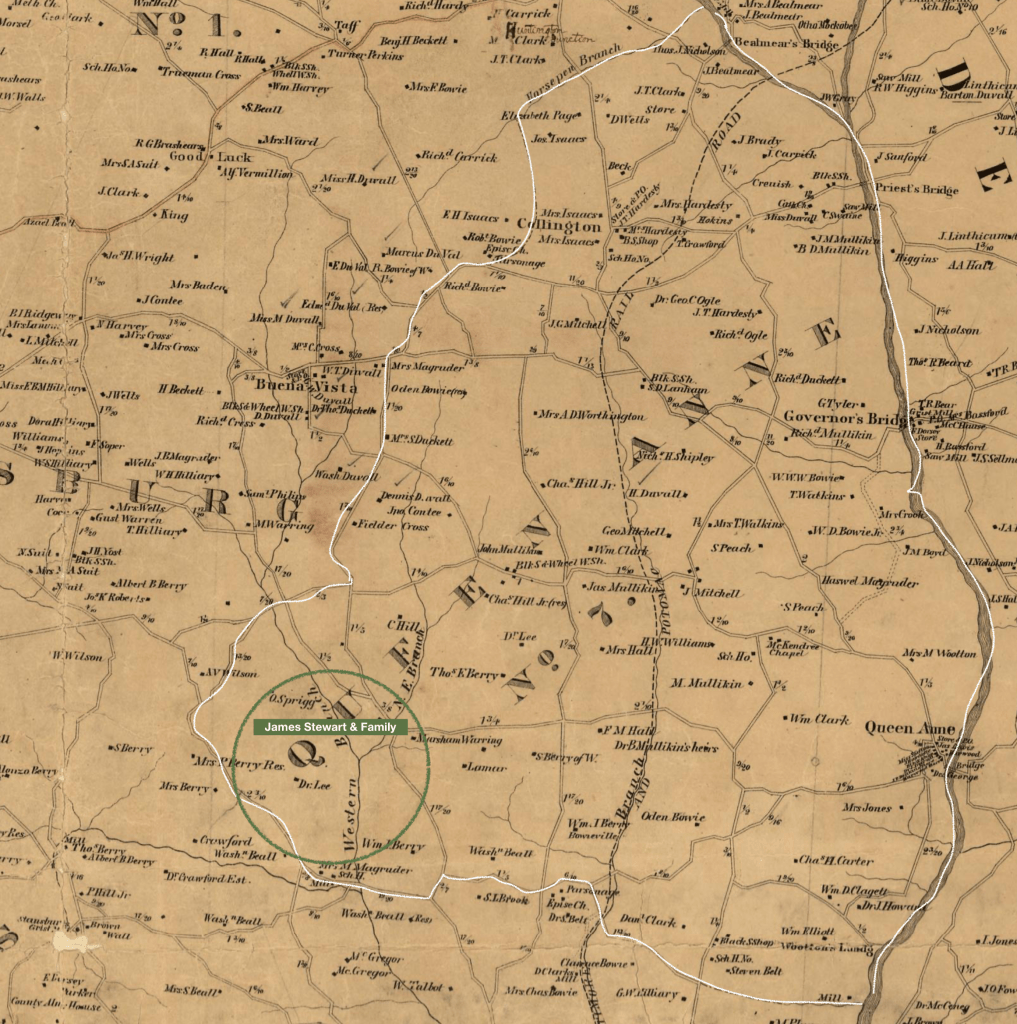

After emancipation in 1864, James Stewart and many of his children, including Notley Stewart, stayed on the lands of Dr. Benjamin Lee in Queen Anne District in Prince George’s County, Maryland.

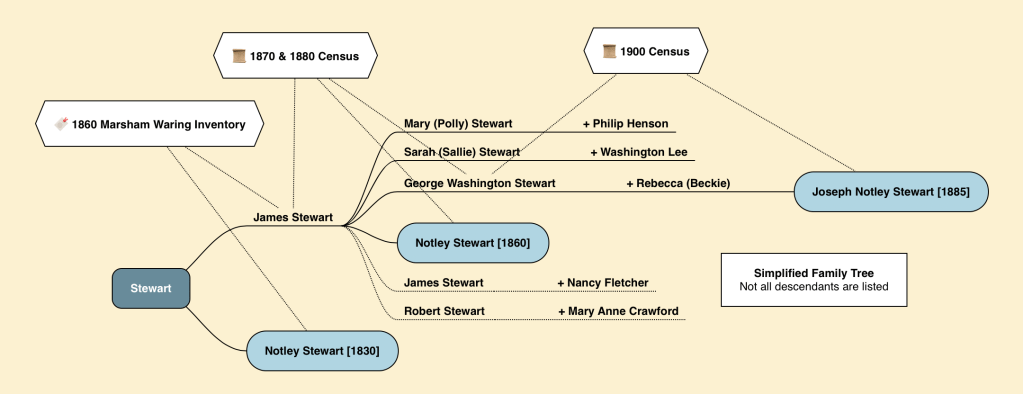

Prior to emancipation, Stewart had been forced to labor for Marsham Waring’s estates, while his children labored on the estates on the Lee. Waring and Lee were brother-in-laws. Inventory records for Marsham (WAJ 2:321) and the post-emancipation records of the 1870 and 1880 records suggests that James was born a few years after 1800, and about a decade after Marsham Waring.

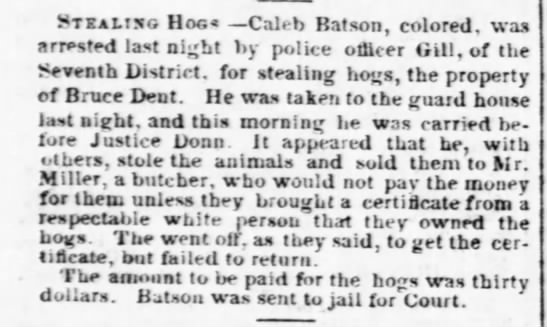

The name “Notley” has been used by multiple generations of the Stewart family — and one possible source for the given name is from the enslaver Notley Young. Other members of the Stewart family used names that were aligned to their (former) enslaver. For example, James’ son and daughter-in-law, George and Rebecca Stewart had daughters named Violetta and Eleanora, both names in common with the wives of Waring and Lee. Sarah (Sallie) Stewart and her husband Washington Lee named one of their sons, Benjamin, giving him both a given and surname that matches Sarah’s former enslaver, Dr. Benjamin Lee. The use of Notley in the family suggests a connection with a (former) enslaver named Notley, i.e., Notley Young.

There are three Notley Youngs in three successive generations:

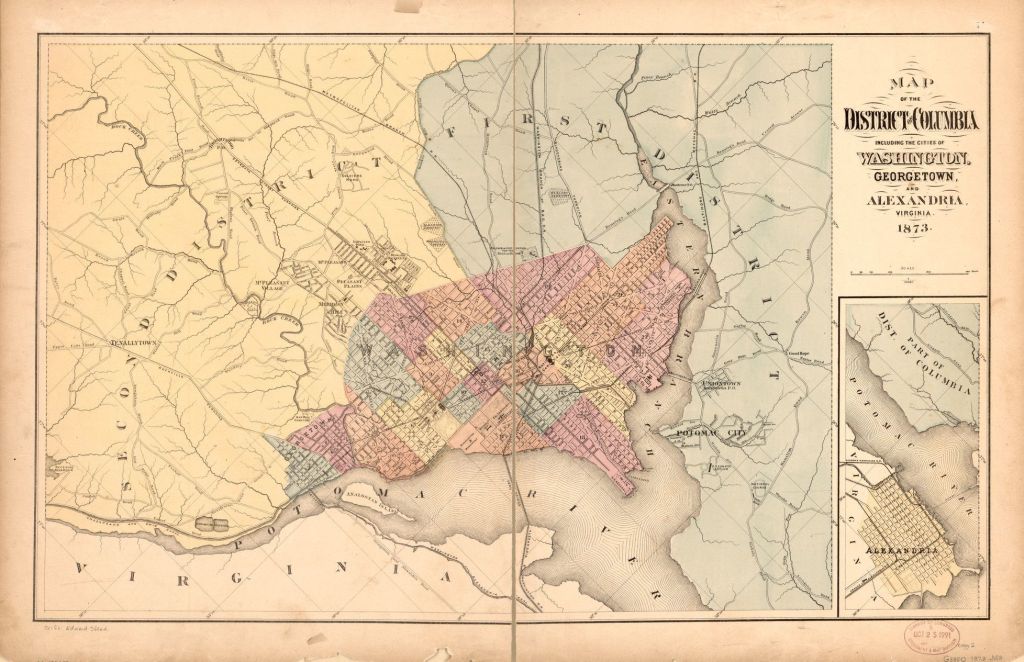

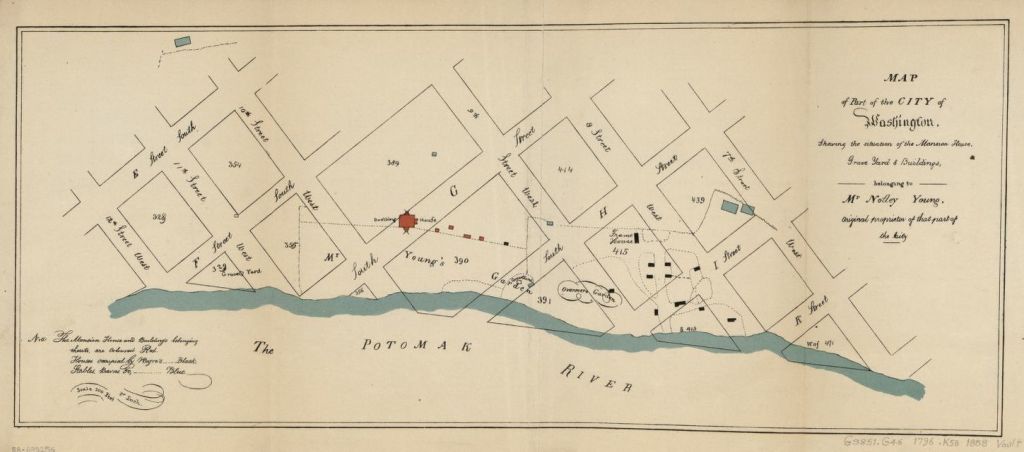

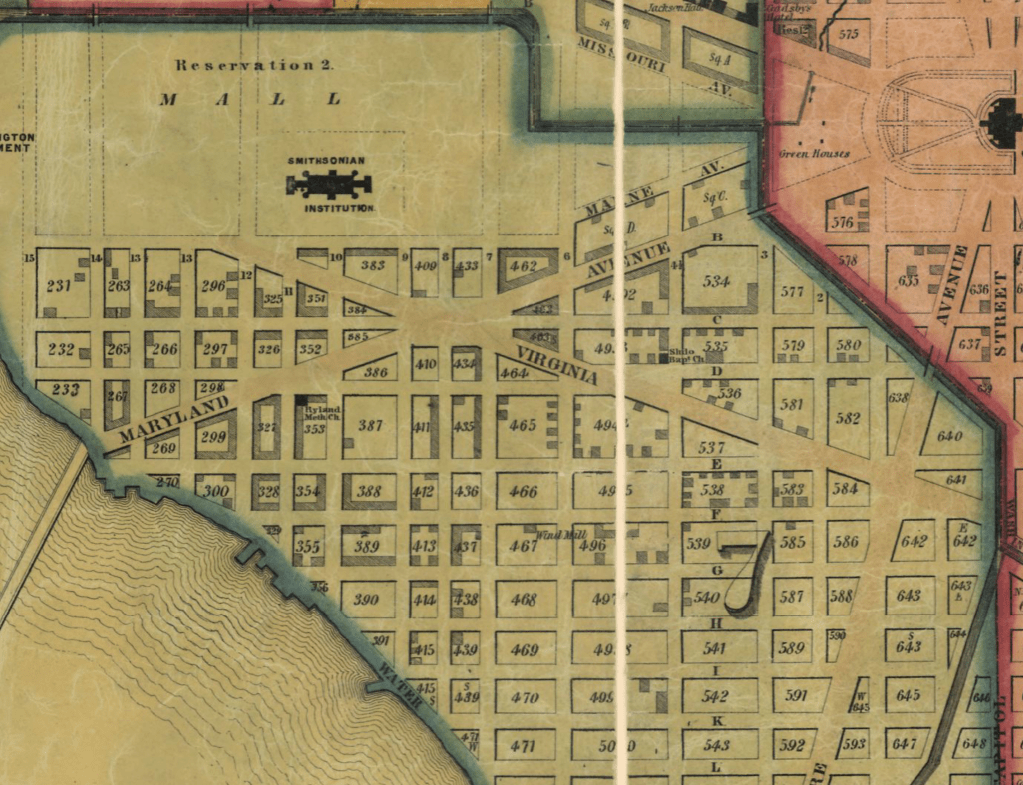

- Notley Young (I) who died in 1802. His estates and property were located within the parts of Prince George’s County that would become the District of Columbia.

- Notley’s (I) son, Notley Young (II), a priest with connections to the Jesuits, Georgetown University and the White Marsh plantation along the Patuxent.

- Notley’s (I) grandson, Notley Young (III), son of Benjamin Young. Notley Young (III) married Eleanor Hall, his second cousin, and lived in Queen Anne District, before dying in 1846.

In the 1828 Tax List for Prince George’s County, Notley Young (III) owned practically 735 acres of land in the Collington & Western Branch Hundreds, from which part of Queen Anne District would become. Both Waring and Lee owned property before the Civil War along the Western Branch, which divided the two hundreds.

Inheritance

There are three ways to acquire an enslaved person: 1. purchase, 2. inheritance/gift, or 3. natural “increase”, i.e., claiming ownership of the children of enslaved women.

James Stewart was born prior Marsham Waring acquiring his father’s estate, who died in 1813. On his inventory, there was a child called Jim (James) age 12 with an estimate birth year of 1801, which is consistent with calculated birth years from the later documents. This suggests that Marsham Waring (Sr.) conveyed James along with his other property to Marsham Waring (Jr.) of the 1860 Inventory, and opens the line of inquiry of how Marsham Waring (Sr.) acquired him.

Purchase from Notley Young, Sr.

Notley Young’s grandfather died in 1802. Included in his inventory is a James age 3, who would have been born in 1799. This is within two years of the age on the 1813 inventory of Marsham Waring (Sr.) After making some specific bequeathals to his wife and for his real estate, Young’s grandfather divided his personal estate (including his chattel) to be equally divided among his five identified children/grandchildren.

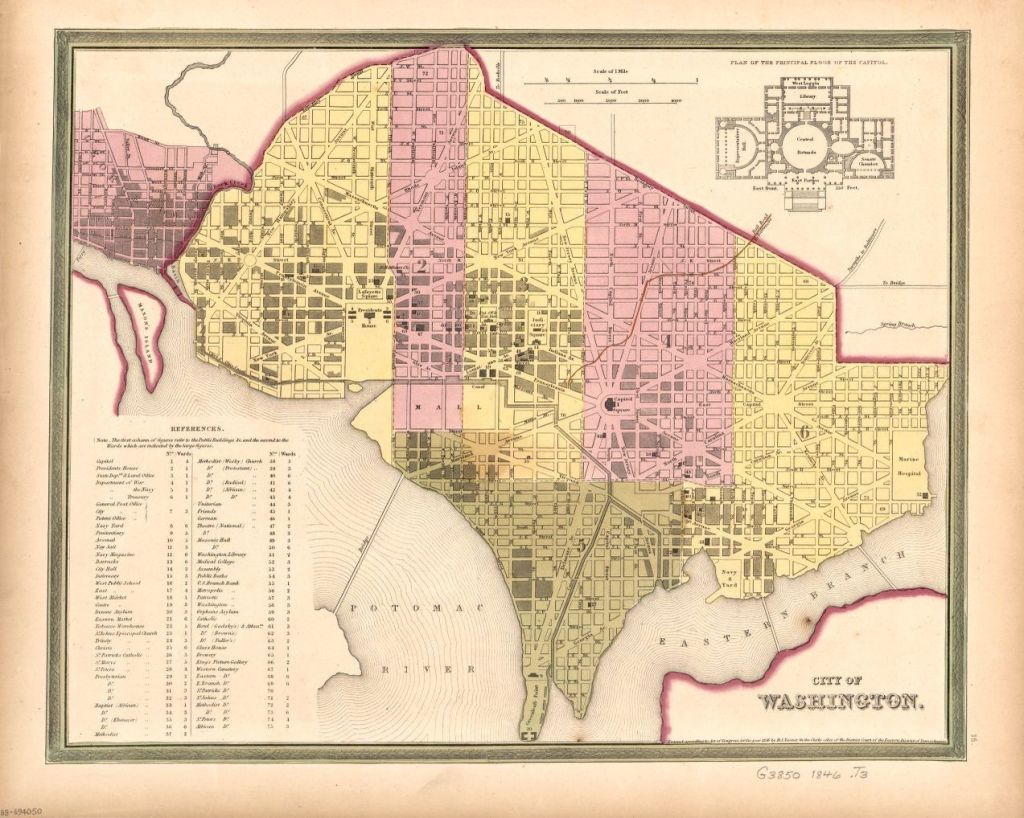

As noted on the family tree, a cousin of Notley Young (II) is George Washington Young, who inherited his father’s estate Nonesuch along the Eastern Branch (what would become known as Anacostia) and within the District of Columbia. When the District abolished slavery in 1862, G. W. Young filed a claim for compensation for his “loss” that included a “Stuart” family group.

This suggests that the Young family had enslaved members of the Stewart/Stuart Family group, perhaps even the one that James Stewart came from.

It is possible that the heirs of Notley Young sold James and separated him from his family, sending him to Marsham Waring (II) and his estates. Both Marsham Waring (II) and Notley Young were involved in the creation of the District of Columbia and engaged in business together. In the 1830s, their heirs were sued as together they had put up sureties for Thomas S Lee and a loan he had taken from Charles Carroll of Carrollton (Charles Carroll of Carrollton vs. Marsham Waring, et al June 1832).

White Marsh Baptism Record

In 1832, the enslaved population of Waring and Lee grew through “natural increase”, the term enslavers used to conflate the language they used to talk about their livestock and their enslaved people, dehumanizing the latter. James “Stuart” and Susan (Suky) had their son, James, baptized by the priests of White Marsh, the Jesuit Catholic plantation near Priest’s Bridge which also enslaved numerous people.

The baptism record notes that James (Sr.) was enslaved by “Master” Warring and that Susan (Suky) was enslaved by Dr. Lee in Marlborough. The record also notes the sponsor/godmother as a person enslaved by Notley Young, mostly likely Notley Young (III) based on the year of the baptism. The name was transcribed as “__rvelide?”.

Dr. Benjamin Lee lived in this house in Upper Marlboro from 1821-1844 before moving to his estate in Queen Anne District. This is where Suky and her children most likely labored.

It is probable that the sponsor for the baptism of James and Suky’s son is a relative of either James or Suky, as godparents are usually chosen from within a kinship group, and therefore suggesting a connection between the Notley Young estates and James Stewart’s kinship group.

Reconstructing the Transcribed Name

My source document provides the typed transcription without access to the handwritten record of the priest, leaving the reader to guess at how the the transcriber interpreted the name. To complicate matters, the priests of White Marsh were not also fluent with Anglo-American names or the diminutives used by the enslaver and so there is often non-traditional spelling. With that in mind, the following three items helped to narrow the possibilities.

- The transcriber noted it was a godmother, therefore looking for women’s names

- The index to White Marsh Book 4 provides three plus page list of names of given names used by the priests, providing a sampling of names used during this time period by enslavers and enslaved.

- The final syllable “-ide”

These three items helped to identify Adelaide and its variations as a probable given name for the godmother. Another possibility includes names like Emeline and its variations, though Matilda and Cornelia are also likelihoods.

Of note, on the same page, a Adelaide was noted as a person enslaved by Benjamin Young, likely Notley Young’s brother. She had a son, Alexander who was baptized the same year as James. In 1818, Sandy [Alexander] and Adelaide were married at White Marsh with the permission of their enslaver, though the record does not note their enslaver. That said, the repetition of Alexander and Sandy in both records suggests that Adelaide and Alexander married and had a son, named for his father, Alexander.

A 1821 records provides more insight into the Alexander + Adelaide family group. Francis and Moses Sandy were baptized in 1821, as one-day old sons of Sandy and Adelaide Cosy, servants of Mr. Benj. Young. In 1817, Peter Corsey escaped from Notley Young, he may be related to the Cosy’s of Benjamin Hall.

A review of the 1809 Inventory (TT 1:321) for the estate of Benjamin Young (the son of Notley Young (I) and the father of Notley Young (II) and Benjamin Hall Young provided a possible family group for Adelaide. The Inventory appears to be groups in families, as a few adults will be named then children, then adults and children again. The group identified occurs near the beginning of the inventory. The list includes a Suck, a name variation for Susan; though Susan was an extremely common name for the enslaved communities of Prince George’s County.

| Name | Age in Inventory | Estimated Birth Year |

|---|---|---|

| Dolly | 32 | 1777 |

| Eliza | 21 | 1788 |

| Suck | 15 | 1794 |

| Louisa | 12 | 1797 |

| Adelaid | 10 | 1799 |

| Harry | 12 | 1797 |

| John | 10 | 1799 |

| Billey | 10 | 1799 |

| Maria | 4 | 1805 |

| Chrissy | 5 | 1804 |

| Edward | 3 | 1806 |

| Ned | 4 | 1805 |

| Robert | 2 | 1807 |

Tentative Conclusion

The circumstantial evidence suggests that James Stewart came to the Waring family from the Young family.

- The use of Notley as a given name within the Stewart Family

- The presence of a James on the 1802 Notley Young (I) Inventory

- The inclusion of other Stewart family groups on the Compensation List for G. W. Young

- The presence of a White Marsh baptism record which indicates a godmother from the Notley Young estate for James Stewart’s son, James (Jr.)