John Woodard lived most of his life area between Sheriff Road and the current Central Avenue in Prince George’s County.

Prior to the Civil War it was Bladensburg District and after the war the district was divided and he lived in the part was christened Kent District.

He was married twice, first to Rachel Contee and second to Sarah Jones. He was drafted into the USCT and after the war, returned to his family and the land which he continued to labor for the profit of others, his life before and after emancipation connected to the white Wilson family that had been his enslavers.

USCT

He was drafted in July 1864, the Baltimore Sun listing him as “John Woodward, slave of Virginia Wilson“. The enlistment of Black men into the army was a matter of controversy in Maryland, as both slaveholders and non-slaveholders protested various directives and commands that first enlisted free Black men, which appeared to favor slaveholders by exempting the enslaved, and then the slaveholders protested the confiscation of their property. Ultimately, the slaveholders received compensation for their male slaves who enlisted (See Slavery and Freedom on the Middle Ground, Chapter 5).

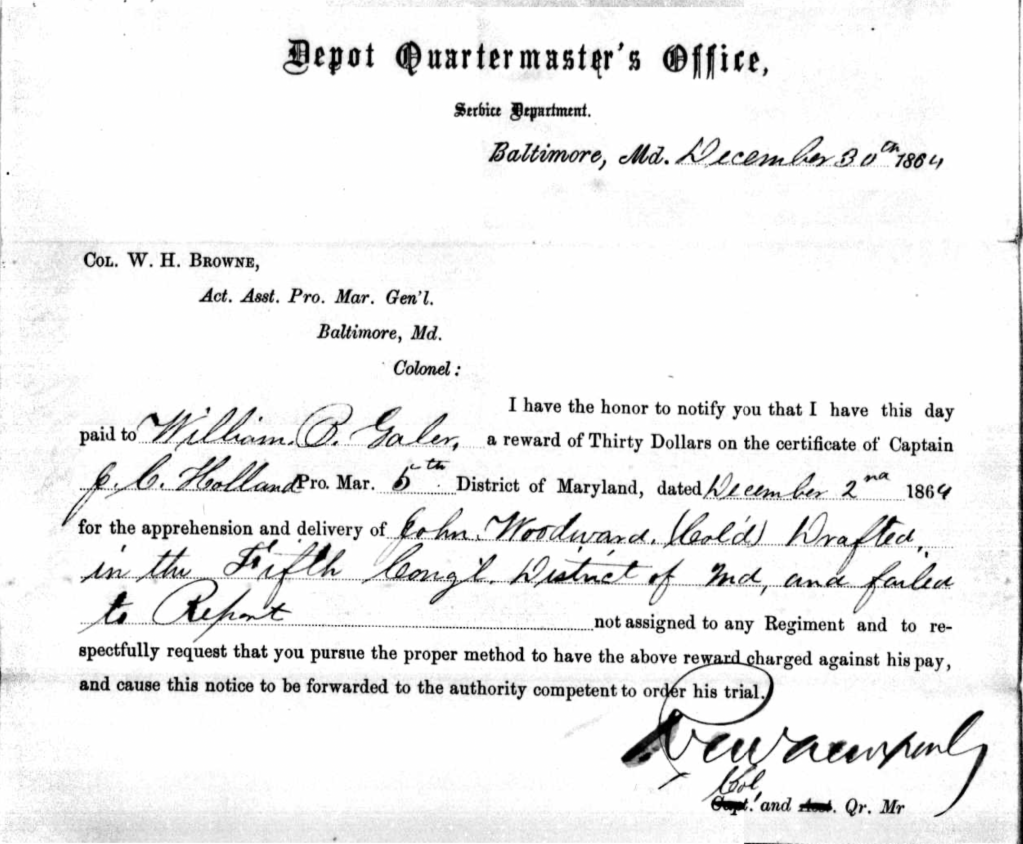

Woodard’s service records notes that he “failed to report” and in Dec 1864, he was arrested in Prince George’s County and brought to John Woolley, provost marshal for Baltimore. Later in 1866, the charger of desertion was removed due to “Special Order 15” suggesting that Woodard had been prevented from reporting as opposed to actively resisting enlistment.

With the exodus of Black people from Maryland seeking freedom and with the enlistment of able male bodies, the number of men aged 20 to 45 were increasingly scarce and his enslavers may have resisted letting go of Woodard. A superintendent of Black recruitment in Maryland told his superiors “whenever the US gets a soldier, somebody’s plow stands still”. (Slavery and Freedom, page 126-127). John Woodward was one of three adult males (the other two were 18 years) claimed by Mortimer Wilson in the 1867 compensation lists.

The records show that William B. Galer was paid $30 for the “apprehension and delivery” of John Woodward to the army. This detail helps to support the idea that Woodward was prevented from reporting to his drafted enlistment.

Galer was a 26-year-old white man living Bladensburg according to the 1860 census. Galer was enumerated living in the household of his inferred mother (DN 681). They did not have listed property (real or personal). Mortimer L. Wilson was enumerated at DN 668 and his widowed mother, Amelia Wilson, at DN 719. Galer’s immediate neighbors were horse traders, hostlers and stage conductor, suggesting that they lived in Suitsville or Brightseat, which was situated between Lawrence and his mother on the 1878 Hopkins map of Kent District. Galer’s father had been listed as a wheelwright in the 1850 census.

After the war, Mortimer L. Wilson claimed $100 for the service of John Woodard in the 4th USCT Infantry Regiment.

Second Wife, Sarah Jones

John Woodard returned to his wife, Sarah, and his children after the war. In 1870, they are living near Philip Hill and Edward Magruder, two landowners connected to the Wilson family through marriages. This places Woodard and his family on Sheriff road which connected the District with Brightseat P.O.

In the 1870 Census they had four children:

- Arthur Woodard, age 14

- Matthew Woodard, age 12

- Ellen Woodard, age 6

- Michael Woodard, age 4

Sarah applied for a widow’s pension when John died in 1892. She included affidavits from William W. Wilson, the son of her husband’s enslaver and as well as two people who served as groomsmen and bridesmaid at her wedding ceremony in 1852. Nathan Thomas and Sallie Hickman served as the witnesses to the ceremony. They attested to the fact that she and John were married by Father Dietz at White Marsh, the Catholic Church near Priest’s Bridge and the Patuxent River.

Sallie Hickman and Sarah (Jones) Woodard were enslaved on the same estate by the Marsham Waring family. In 1900, Sarah (Sallie) Hickman was living with her son on Sheriff Road within the District of Columbia.

Although their enslavers allowed their marriage, they were enslaved on different estates. Sarah raised her children at Warington, the Marsham Waring estate while John remained on the Wilson estate with children from his first marriage.

First Wife, Rachel Contee

The affidavit by William W. Wilson names John’s first wife. He states in his message that “John Woodard was married before to one Rachel Contee and died in June 1848 on “Baltimore Manors” in Kent District, Prince George’s County, Maryland.”

Baltimore Manor was the name of the estate owned by the Wilsons for generations. It sat on the land that FedEx field currently sits on. William Wilson was the father of Washington Wilson, Margery Wilson and Joseph H Wilson and other children. When he died around 1817, portions of Baltimore Manor were bequeathed to Washington Wilson and Margery Wilson and other lands (among them Beall’s Pasture) was bequeathed to Joseph H Wilson, the father of Mortimer L. Wilson and William W. Wilson. Joseph H Wilson acquired portions of Baltimore Manor after the death of his brother, Washington Wilson, in 1825 and a chancery suit. (MHT)

Children of Rachel Contee and John Woodard

In 1867, Mortimer L Wilson claimed John Woodard along with Jeffrey and Eveline/Emeline Woodard, who were about two decades younger than him. Their position in the list and their ages suggests they are his children. The two additional children: Charles and Peggy are children of Eveline as evidenced by later census records.

In 1858, Eveline/Emeline was listed with a William, age 12, and a Jeffrey, age 11 in the inventory for Joseph H. Wilson’s estate. Their grouping would bolster the suggesting that they are siblings. Based on the omission of William in the compensation lists, it would suggest that William was separated from his family by death or sale.

Jeffery Woodard died in Jan 1907 and his death certificate names his parents as John Woodward and Rachel Contee. His estimated birth year of 1847 from the inventory suggests he was born shortly before the death of his mother.

In 1880, Arthur and Matthew Woodward are living with Emily [Emeline] and her husband, Edward Hamilton, and children in the District at 910 Delaware Ave. They are listed as her husband’s brother-in-laws.

Rachel Contee

Rachel Contee died around 1848 and before the inventory of Joseph H Wilson in 1858. She is not listed in the 1833 Personal Property Assessment for Joseph H Wilson, suggesting that he acquired her after 1833.

In 1841, Joseph H Wilson became indebted to Levi Sherrif for over $5000 dollars. Levi Sheriff was married to Joseph’s other sister, Matilda. As was common, Wilson used the people he enslaved as collateral for the loan. This was recorded in the land records (JBB 1:413). He listed John, age 20, [est BY 1821] which is consistent with John Woodward. He also listed Rachel, age 19, [est BY 1822]. Since Wm Wilson notated that she died on “Baltimore Manor” in the pension affidavit and since her age is similar to John’s in the indenture, this would suggests that this is Rachel Contee.

Death notice for the widow of Joseph H Wilson names Baltimore Manor.

William Wilson, the patriarch of the Wilson family, died in 1817 conveying the main tract of land to his son, Washington Wilson. In 1825, less than a decade later, Washington conveyed the tract to his son, James A Wilson, while Joseph H Wilson was named estate executor and guardian of his nephew. After the death of his nephew, he acquired the property which passed to his son, Joseph K Wilson.