Background Reading

the tapestry of macgill’s estate

The story of Polly is one of resistance against a world designed to commodify her existence. Sold from the estate of her long-time enslaver, she escaped her new owner in a daring attempt to re-stitch the torn fabric of her own kinship community. To understand her actions, one must first examine the complex tapestry of the world that sought to control her.

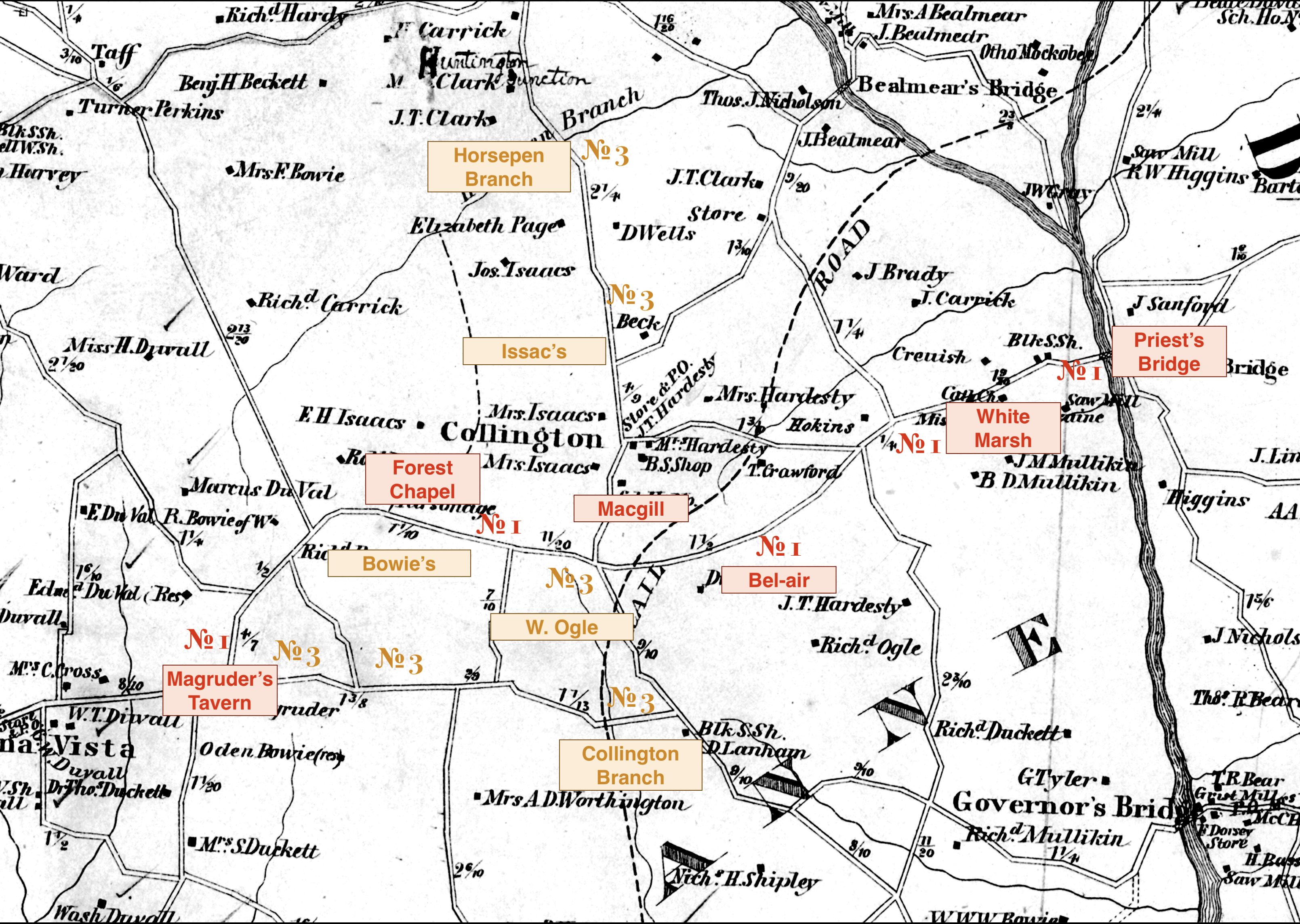

Dr. James Macgill, heir to his uncle of the same name, presided over a sizable estate in Prince George’s County in the 1830s. His 740+ acre plantation was stitched together from various land tracts along present-day Annapolis Road, a significant crossroads in the Vansville District (later Queen Anne District). The estate was bordered by massive operations: the Jesuit’s 2,000-acre White Marsh plantation, the Ogle family’s 2,000+ acre Bel-air estate, and the Bowie family’s 570+ acre Locust Grove. An 1828 tax list documents the human dimension of this operation, enumerating the 34 people Dr. Macgill enslaved: six elders, eleven adults, four adolescents, and thirteen young children under the age of eight.

The 1828 Levy Court Road Survey details the estate’s strategic location, providing access to the Patuxent River and placing it in direct proximity to the Ogle’s Bel-air plantation—the community where Polly’s future husband, Peter, was enslaved.

Road No. 1 [now-Annapolis Road]: Commencing at the Priests Bridge on the Patuxent, thence through the White Marsh Plantation; then through Bel-air, thence through the plantation of Dr. James Magill by the Forest Chapel, thence by Magruders Tavern…

Road No. 3: …across Collington Branch, thence with the plantations of William Ogle, James Magill, and Walter Bowie…

Married to Julia Ann Compton in 1829, Macgill also owned property in Anne Arundel County near West River Post Office and Samuel Carr, the husband of Mary Compton. The property was situated in the First District along the road that led to Mount Pleasant Ferry, connecting Anne Arundel to Prince George’s County closer to Upper Marlboro, the county seat. The estates wove together the family’s interests across two counties, creating a broader and more complex tapestry of land and human property.

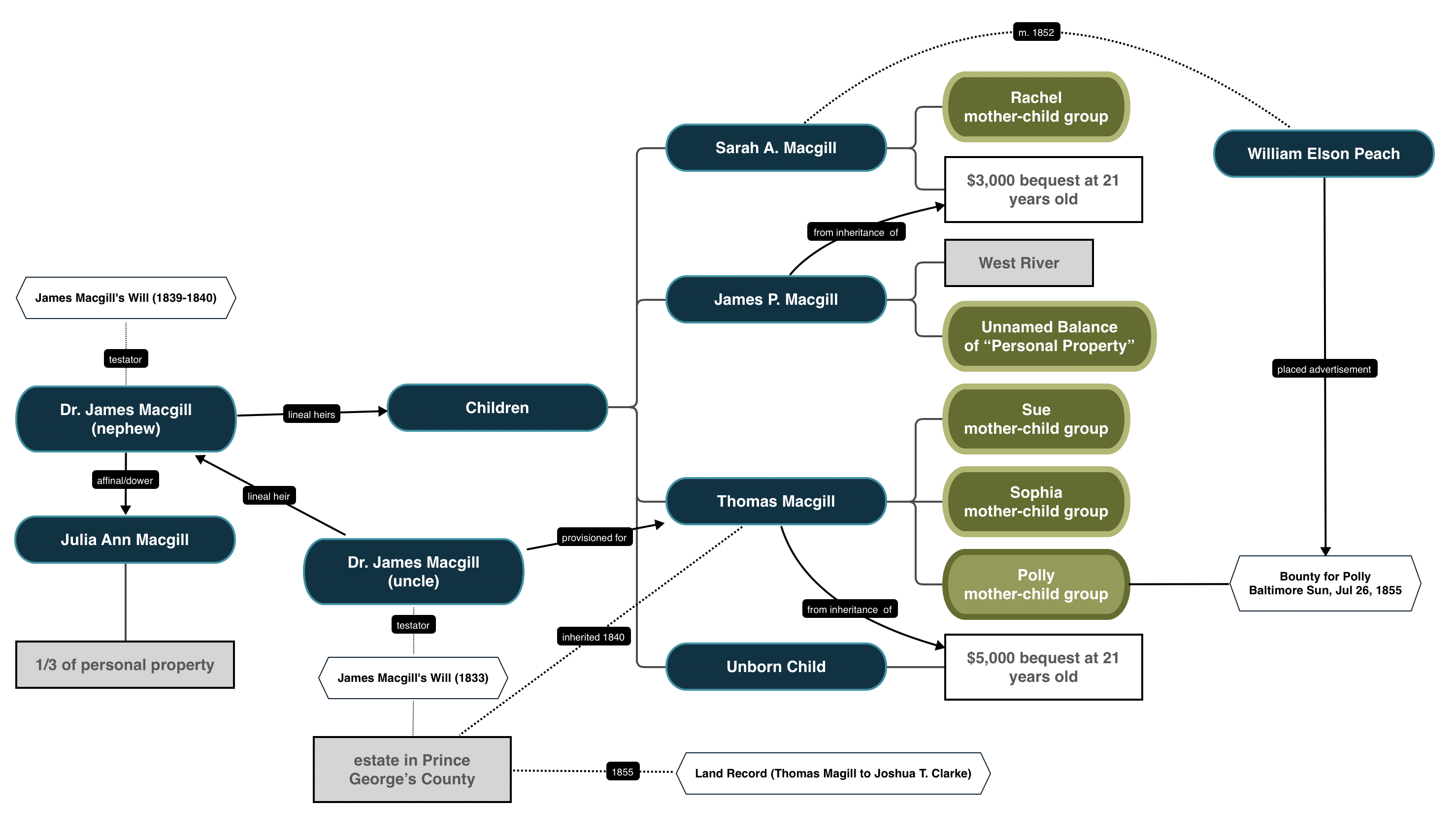

the Snag: the death of the patriarch (1840)

A decade after his marriage, Macgill’s impending death created a snag in the tapestry of his estate, and he composed his last will and testament, dividing his real and personal property among his wife and three born children, while making provisions for his unborn child. Like his uncle, he dictated how the fabric of his estate was to be cut and divided, specifically naming different mother-child family groups and directing the heir who would acquire four family groups, with a third being conveyed to Macgill’s wife as her right of dower, and the unnamed “balance” going to James P. Macgill.

ripped threads of kinship

Macgill’s division in his will ripped the threads of kinship among the community enslaved on his estates. While he nominally kept mother-child groups together, Polly and her children were divided from her larger extended family. As the wife of Peter, she became part of the larger Lee family group, and with Macgill’s will, she was separated from Harriet Lee and her children, Daniel, Oswald [Osborn], Caroline, Ann, and Amelia, who, while unnamed in the will, were named in the inventory and much later in the 1867’s Compensation List of Septimus J. Cook, the second husband of Julia Macgill. Whereas, Polly and her children were conveyed to Thomas Macgill, the oldest son, who would also receive a sizable portion of the Prince George’s estate through provisions of the 1833 will of the older Dr. James Macgill. Polly, Peter, their children, and the family of Harriet Lee were the threads that gave the plantation its texture and life. Macgill’s death subjected these threads to immense strain. They were stretched thin across counties, torn from one another, and tangled with new and unfamiliar threads.

threads of inheritance

The will, far from ensuring a smooth transition, pulled the tightly woven kinship community of the enslaved in three distinct directions. Each heir represented a thread pulling part of the tapestry away from the whole. These distinct lines of inheritance did not exist in isolation; they actively pulled the community apart, a process accelerated by the legal and personal entanglements of the heirs.

the dower of the widow: the cook connection

Under Maryland law, Julia Ann Compton Macgill had a dower right to one-third of her husband’s property. This included the enslaved families Macgill designated for her, most notably Harriet Lee and her children. When Julia remarried to Septimus J. Cook in 1845, her dower portion—including Harriet’s family—was legally absorbed into the Cook household. This single act pulled an entire branch of the original enslaved community away, transplanting them into a new network under a new enslaver.

the son’s portion: the line of thomas macgill

Thomas Macgill’s inheritance was anchored in Prince George’s County. As stipulated in two generations of wills, he received a large portion of the home plantation and legal ownership of Polly and her children. While this provision placed Polly in the community where her husband Peter lived, it rested on the financial acumen of the Magill’s guardians to maintain a sizable estate without need to sell off “assets” This thread represented the patriarchal line of succession from uncle to nephew to son.

the balance of the estate: the line of james p. macgill

The younger son, James P. Macgill, inherited the family’s Anne Arundel County property near West River, along with the “balance” of the enslaved people not otherwise assigned. This act created an immediate geographic fracture in the community, moving another group of individuals to a different county and physically separating them from the kinship network on the home plantation. This thread established the West River estate as a distinct, yet connected, Macgill holding—and created the destination Polly would later seek in her flight.

The division of human property among Julia, Thomas, and James P. Macgill set the stage for further disruption. The fifteen years that followed Macgill’s death were marked by a cascade of events—probate, remarriage, and death—that continued to unravel the fabric of the enslaved community.

unraveling in motion: 1840-1855

Multiple events occurred in the years after Macgill’s death that led to self-liberation of Polly in 1855. First, there was the division of the estate as it traveled through probate, followed by the marriage of Julia Macgill to Septimus J. Cook and her subsequent death in 1846, and the re-division of her estate with her children’s. There were sales to settle the debts of the estate. Ultimately in 1855, Thomas Macgill sold his estate that inherited from his uncle to Joshua T. Clark, a neighbor and Justice of the Peace. It is most likely this sale that prompted Polly to seek ways to weave a new beginning for her family.

Polly’s design: weaving against the grain

The impending 1855 sale of the plantation from Thomas Macgill to Joshua T. Clark likely acted as the final catalyst. In response, Polly leveraged her social capital within the enslaver’s network to reach out to William Elson Peach, her late enslaver’s son-in-law. She initiated her own sale, requesting that Peach purchase her to ensure her continued proximity to her husband, Peter. However, while navigating this arrangement with Peach, she almost certainly utilized her own community’s social networks to connect with individuals who offered an alternative path. The “designing person” mentioned in the subsequent bounty notice suggests Polly was not merely seeking a new enslaver but was simultaneously orchestrating an escape. This was her attempt to gather the scattered threads of her own kinship and find lasting liberty beyond the reach of Peach, Clark, and the unraveling Macgill estate.

Sources

1828 Tax List, Prince George’s County

1828 Levy Court Road Survey, Prince George’s County

Marriage Records, for the Macgill-Compton union (1829) and the Macgill-Cook union (1845)

- Maryland, U.S., Compiled Marriages, 1655-1850

- Maryland, U.S., Compiled Marriages, 1667-1899

Last Will and Testament of Dr. James Macgill (the elder), 1833, PC 1:1

Last Will and Testament of Dr. James Macgill (the nephew), ca. 1840, PC 1:129

Probate Records, Estate of Dr. James Macgill (the nephew), post-1840, which would include:

- Inventory and Sales Records of the Estate (PC 4:43, 57, 299; JH 1:20,107,268, 273)

Land Records, for the sale of the Macgill estate to Joshua T. Clark (ca. 1855); EWB 1:137

Newspaper Bounty Notice for the capture of Polly (1855), Baltimore Sun, newspapers.com

1867 Compensation List of Septimus J. Cook