Abraham (Abram) Henry enlisted in the 1st Regiment of the US Colored Infantry in June 1863, when the regiment was being organized in the District.

His service records indicate that he was a free man and as such could receive $100 bounty for enlisting.

Alexander Hawkins was another free man who joined the same regiment and same company, who was also from Upper Marlboro. Neither man is found in the 1860 census for Prince George’s County.

Both men enlisted a year after the abolition of slavery in DC, and in that year, many enslaved people in neighboring jurisdictions fled their enslavers and the estates where they were held captive, escaping to DC where they could claim freedom. This flight came at the risk of encountering slave patrols and constables who preyed on Black people (regardless of official status), capturing them, confiscating their property and (re)enslaving them.

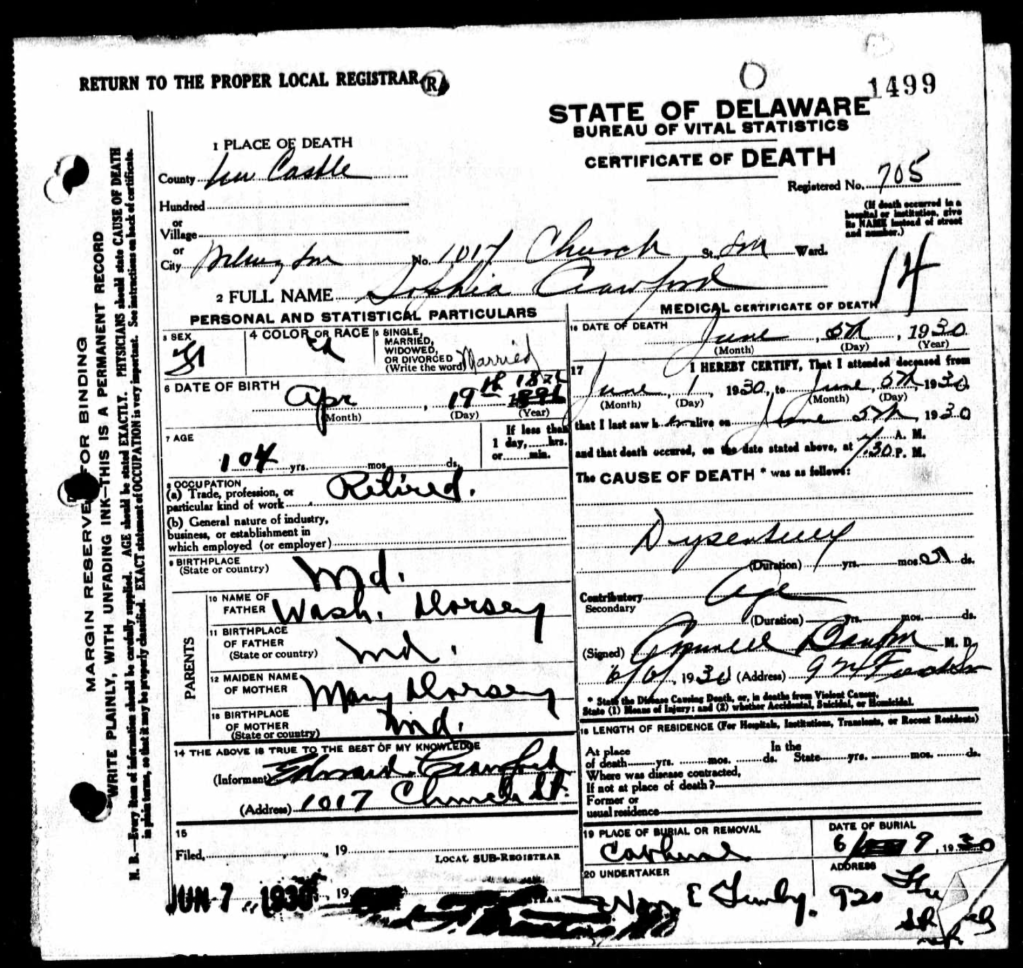

Chandra Manning wrote in her book Troubled Refuge: Struggling for Freedom in the Civil War, that “despite the chronic threat of kidnapping, refugees from Maryland could at least hope to blend in among the capital city’s free black community.” With the abolition of slavery in DC, it is likely that Abram Henry claimed free status in an attempt to avoid recapture and a return to an enslaver. This theory is supported by documentary evidence both in Henry’s service record and in the registrations kept by the Freedmen’s Bureau. Henry’s wife, Celia, was living in a refugee camp.

Celia Henry

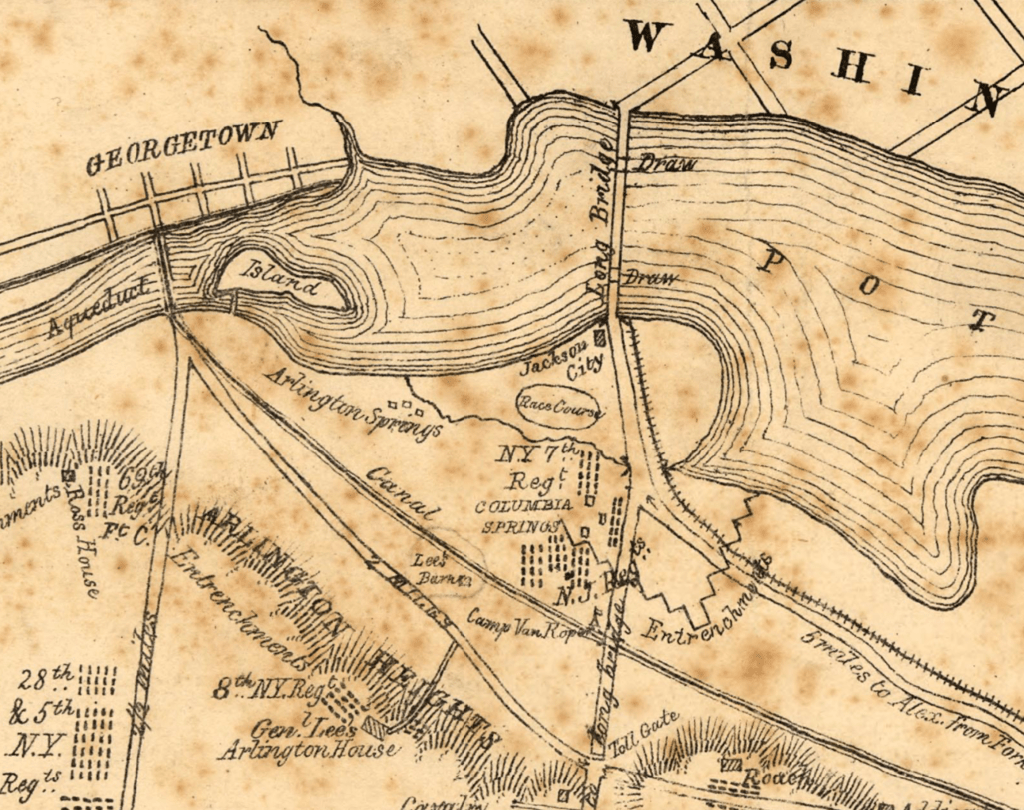

Freedmen and refugees gathered in the presence of the Union troops. Manning wrote, “Wherever the Union army went, tens of thousands of enslaved men, women, and children made their way to its blue lines, braving almost unimaginable risks to get there. They gambled against dogs, heavily armed search parties, jittery Confederate and Union pickets who might shoot at the very sound of an unexpected footstep…Still they came. Still they found work where they could. Still they aided the Union army when and where they were able.” Celia Henry and her two younger children are listed in the registration for the Freedmen’s Village, situated on the bluffs on the confiscated lands of the Lee family, where the federal government was creating a series of forts and entrenchments to protect the capital city.

Another record has her registering at Camp Wadsworth, one of the camps set up in Arlington to house the refugees and provide opportunities for employment. Camp Wadsworth was established on the land of Cooke, who had rebelled against the federal government and crossed to the confederacy. The Union army seized his land near Langley and converted it to Camp Wadsworth. There about 200 refugees grew winter wheat, corn, oat, potatoes, cabbage, turnips, buckwheat, melons, tomatoes and garden vegetables. Men are paid from $8 to $10 a month with rations and quarters. (Birmingham Daily Post, 02 Jun 1864) The Buffalo Morning Express reported that some of the crops grown were used as rations in the hospitals (04 Aug 1863)

Family Names

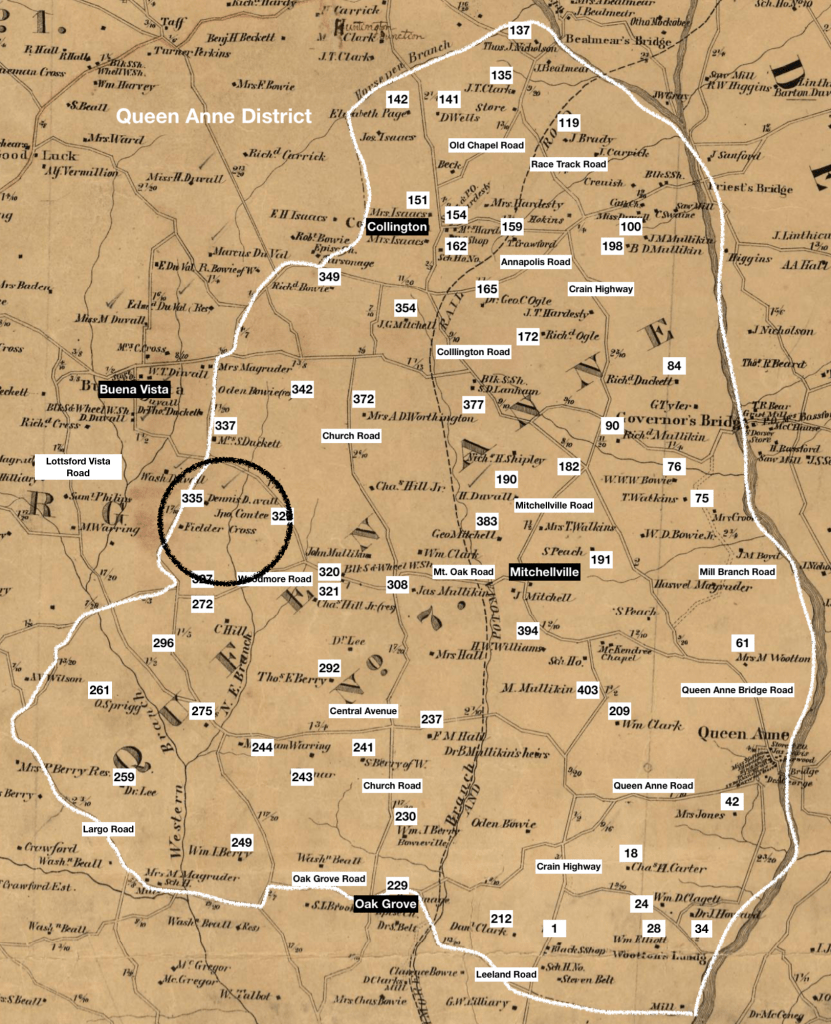

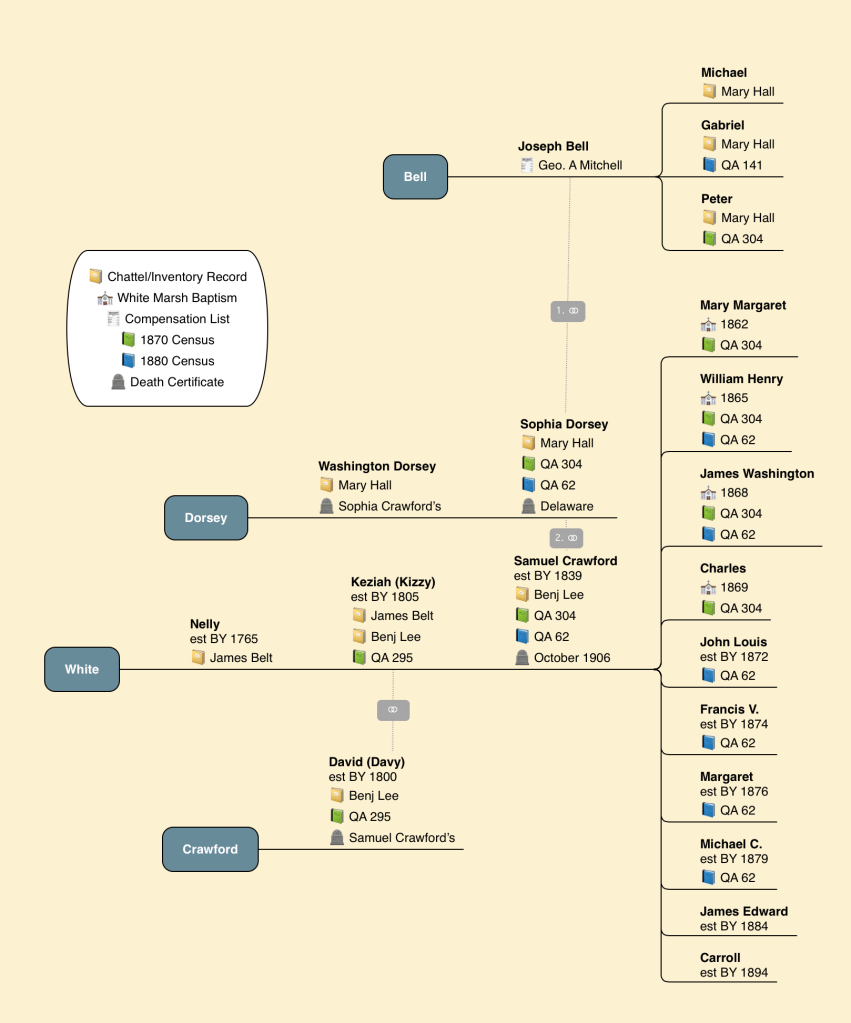

In addition to the record of Celia Henry finding refuge at Arlington Heights and at Camp Wadsworth, there is a pattern of family names that suggest that Abram Henry and his family escaped from Charles Hill.

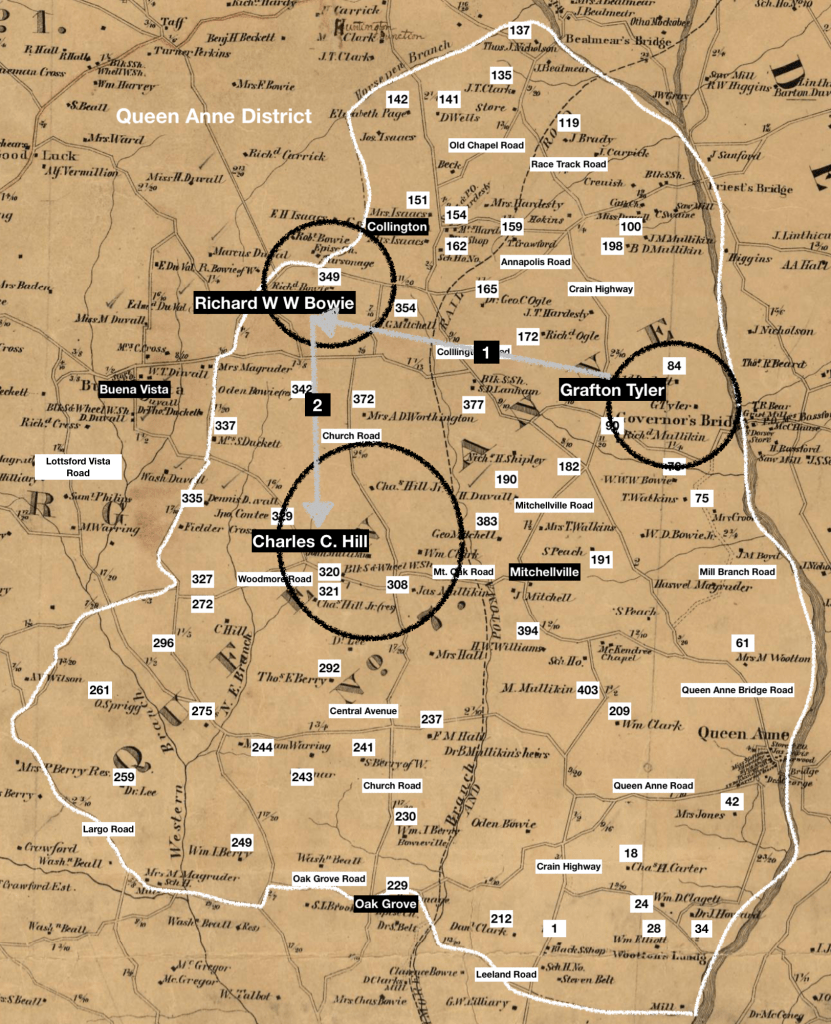

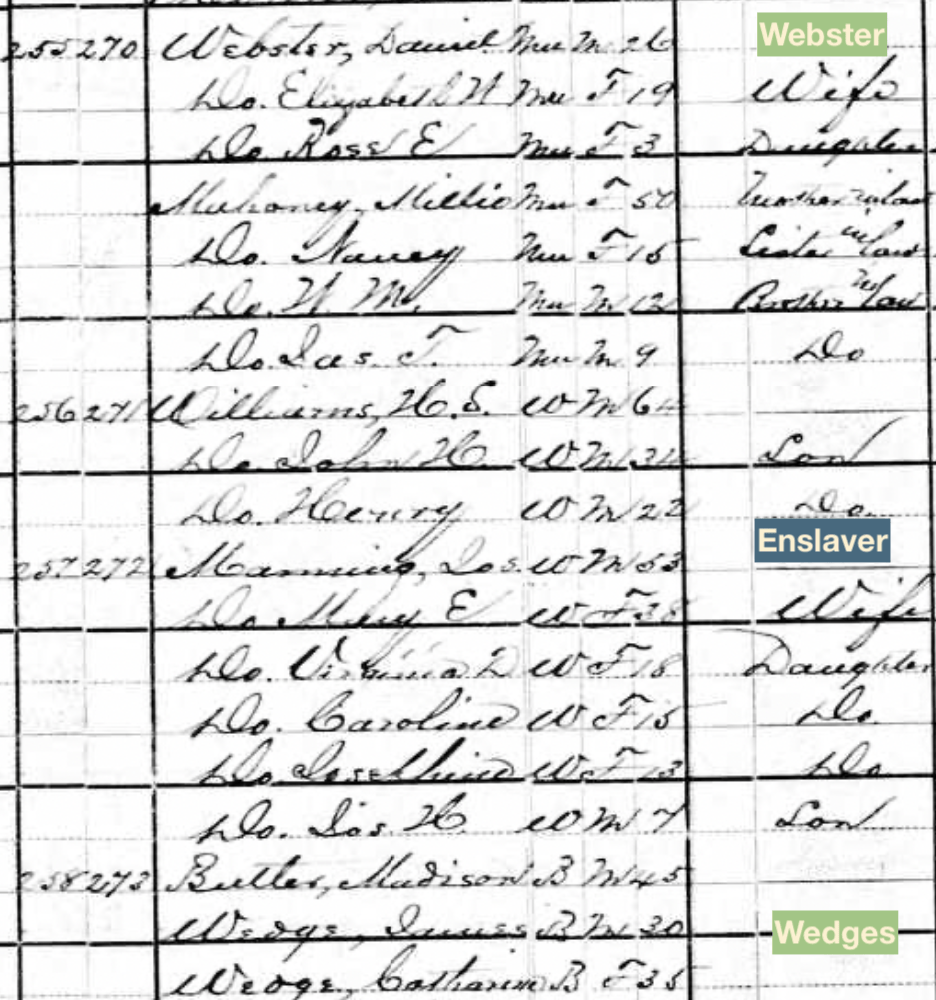

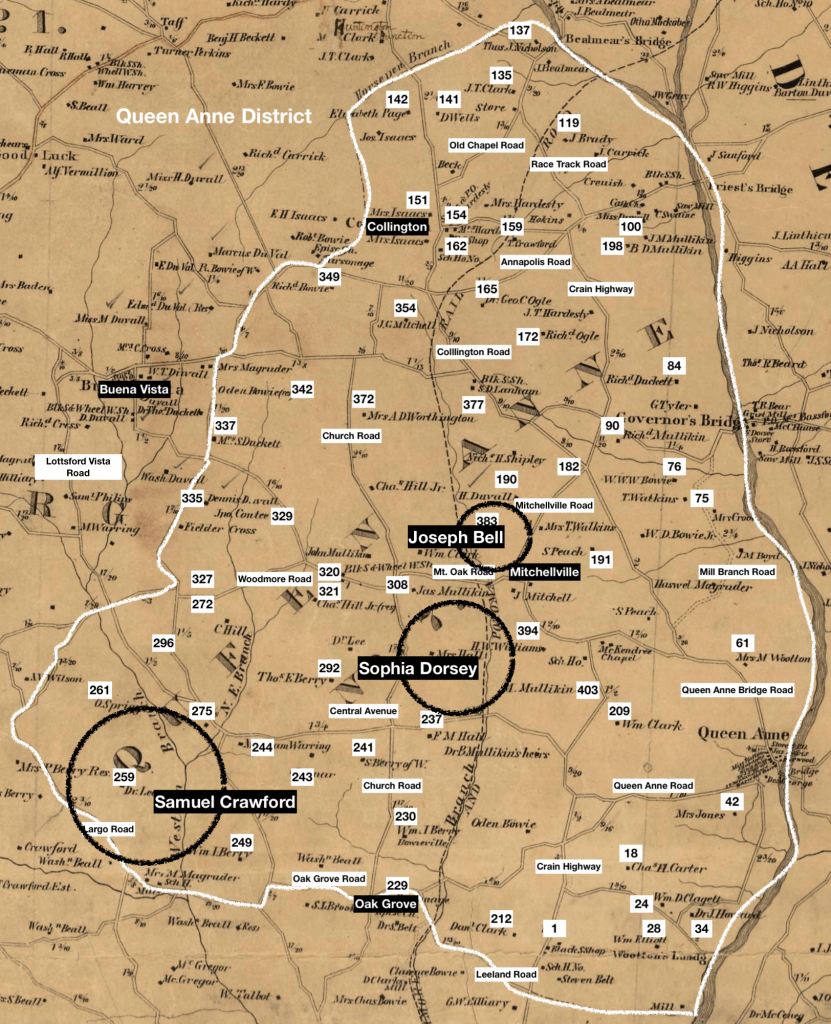

Charles Hill, and his son, Charles C. Hill were among the largest slaveholders in Prince George’s County. They owned substantial estates in both Marlboro and Queen Anne District. In the 1860 census, Charles Hill’s real estate was valued at $300,000 and his personal estate (which included the value of commodified enslaved people) was $215,000. His son had real estate at $83,000 and a personal estate of $71,720. They enslaved around 280 people according to the 1860 US Slave Schedule.

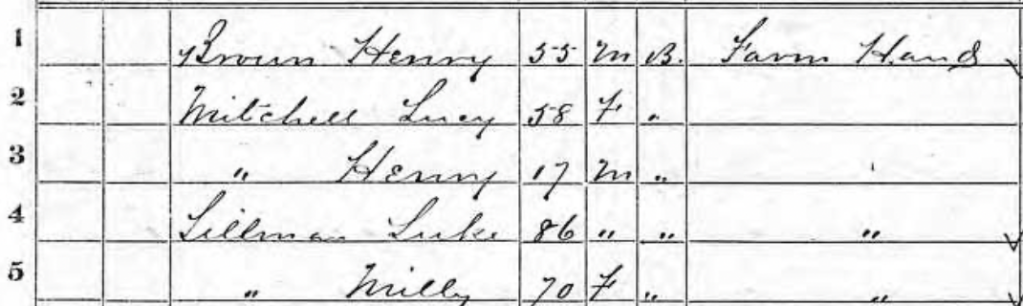

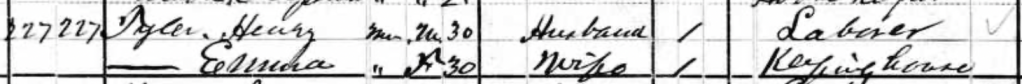

In 1867, Charles C. Hill submitted compensation lists for himself and on behalf of his father’s estate, listing the given and family names of those he enslaved. Among the lists are the family names, Henry and Hawkins, the same family name as Abram Henry and Alexander Hawkins who enlisted as free men. In fact, the Hill family was the only family to submit the name Henry as a family name.

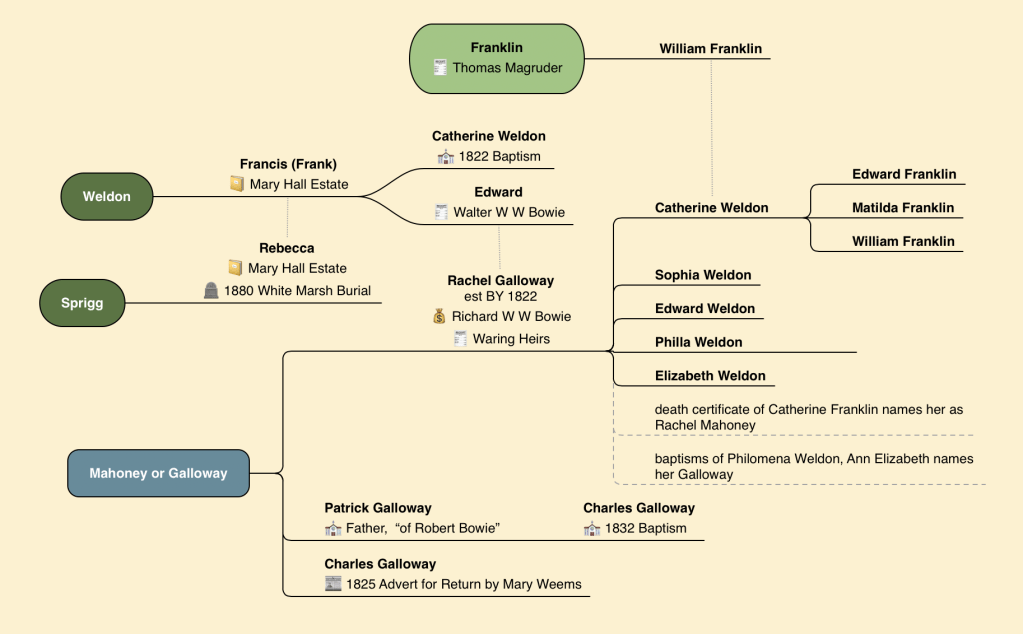

A review of the Freedmen’s Bureau registration lists shows other family names connected with the Hills’ compensation lists: Holland and Diggs. The Hill family claimed 35 people with the family name Diggs, and a Holland family. The Holland family was smaller: four people, one of whom was named Martha and her two children, who were the same approximate age of those in the Registration list.

The evidence is circumstantial and indirect — and it is possible that documentary evidence exists that counters this hypothesis. And yet, the evidence that has been found suggests the possibility that Abram and his wife Celia escaped to DC with their children, and Abram signed up to fight in the newly created regiment of the Colored Troops while Celia sought refuge at the freemen’s camps.

After the war, they returned to Prince George’s County where they raised a family, having many of their children baptized by the priests of White Marsh a Jesuit Plantation with connection to Charles Hill and other wealthy Catholic landowners.