genetic thread: a DNA connection

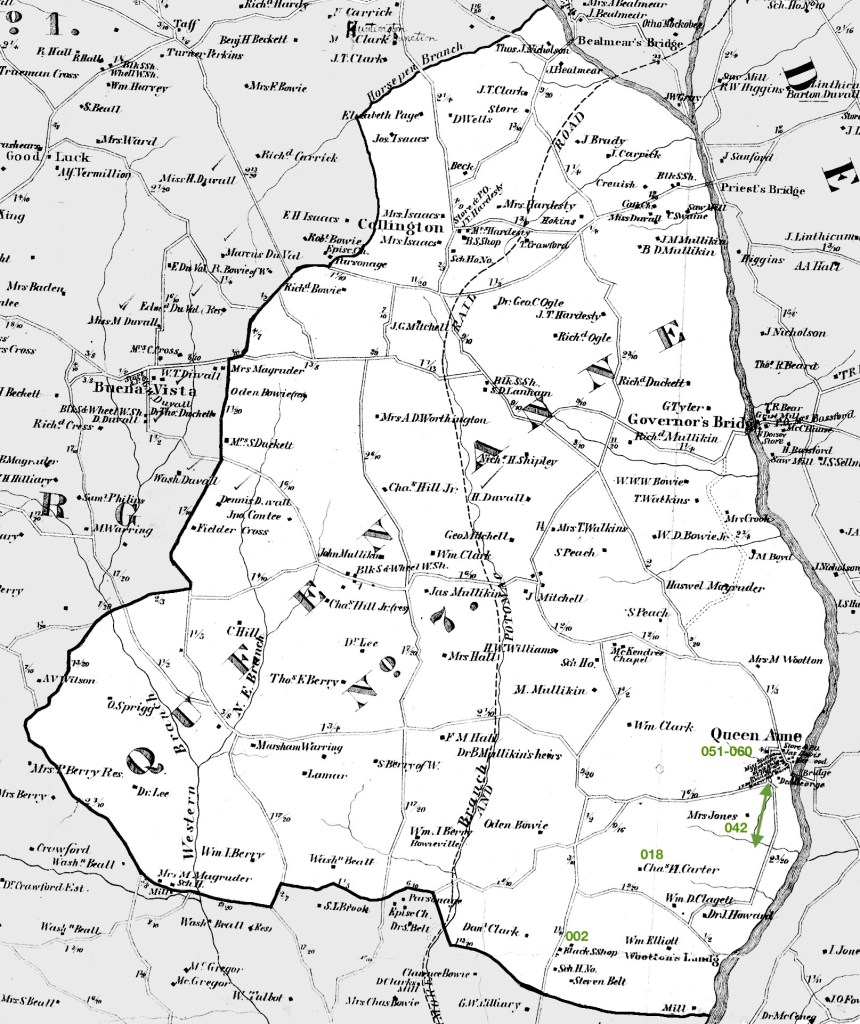

A DNA match between descendants initiated an investigation into the probable shared ancestry of two Black individuals living in Prince George’s County after emancipation. Washington Lee, a Civil War veteran, appeared in the Western Branch Neighborhood of Queen Anne District after the Civil War without visible connections to any kinship clusters. In contrast, Maria Matthews, with her husband and children, could be traced to Bel-Air, the Ogle estate situated relatively near Governor’s Bridge. This genetic link between the two individuals suggests a shared ancestry, offering a rare glimpse into the kinship networks formed under chattel slavery in antebellum Maryland.

historical threads: the documentary evidence

Maria Matthews, daughter of Peter Lee

Maria Matthews died in 1903, having lived in Prince George’s County for the majority of her life. Her death certificate identified Peter Lee as her father. This discovery potentially linked Maria Matthews and Peter Lee to Washington Lee, as a shared family name emerged. An elderly Peter (born circa 1800) was listed in the probate records of the Ogle network along with Maria, corroborating the connection between Bel-Air and Maria’s lineal family.

Polly, Wife of Peter

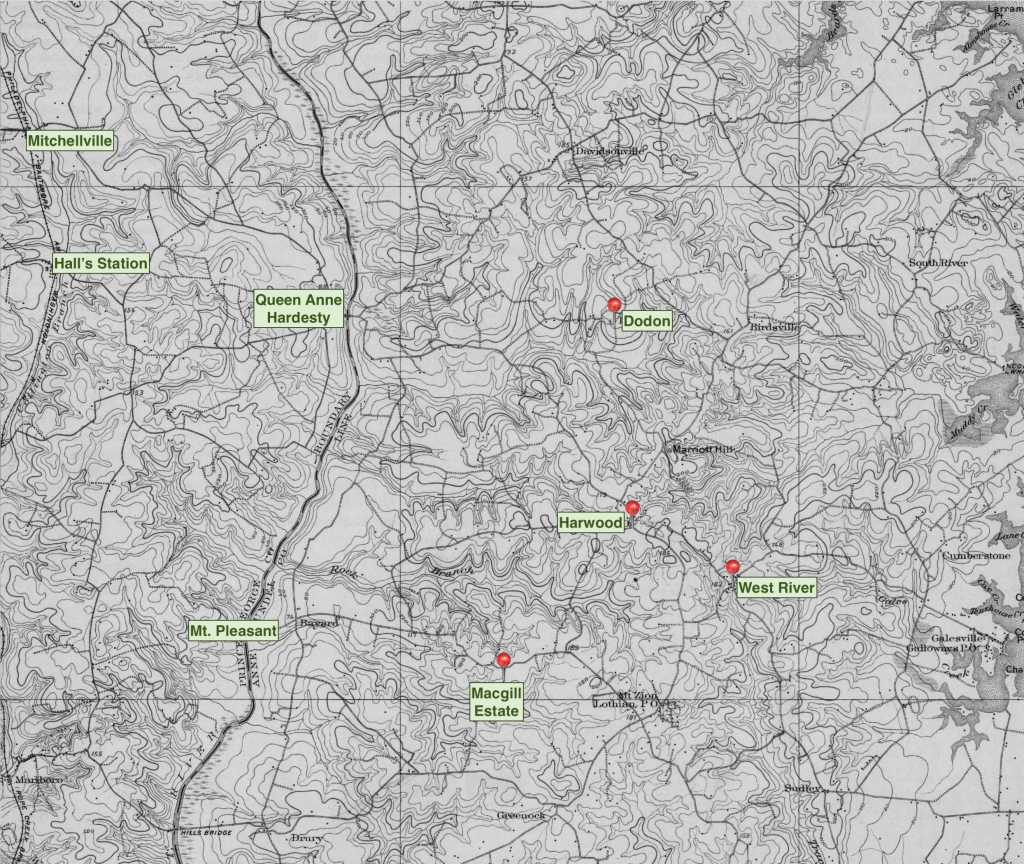

In 1855, Polly, a woman not less than 40 years old, self-liberated herself from William E. Peach. Peach had purchased Polly from the Macgill estate “at her request so that she may enjoy the society of her husband and relatives.” Peach included a certification from Geo. C. Ogle stating that Polly’s husband, Peter, was “anxious that she come home to her master.” Despite Peach’s apparent fulfillment of her request, Polly was not convinced of his purchase and left Prince George’s County, making her way to West River Post Office in Anne Arundel County. Polly had been enslaved on Macgill’s Prince George’s estate, which bordered Bel-Air, where her husband was enslaved. Her journey to West River, in Anne Arundel County, where Macgill’s second estate was situated, suggests the presence of kin in bondage in that location.

Washington Lee, a man of two counties

Washington Lee, a man without readily apparent kinship connections, lived in both Prince George’s County and Anne Arundel County after the Civil War. Marrying Sarah Stewart in Upper Marlboro in 1870, he lived in and around Oak Grove Post Office before moving to Anne Arundel County, near the post offices of Dodon and Harwood, in relative vicinity of West River Post Office. In his waning years, he returned to Prince George’s County to be cared for by his daughter. This combination of Washington Lee’s geographic connections to West River and Queen Anne District, along with the DNA match to Maria Matthews and, presumably, Peter and Polly who also spanned both districts, suggests that Washington Lee was connected with the Lee individuals enslaved on the Macgill estates.

Washington, a boy in the records

A boy named Washington is listed in the probate records of James Macgill. He was held in bondage on Macgill’s Anne Arundel estate near West River, the same area Polly traveled to after her self-liberation from Peach. He was 13 years old in 1844, suggesting a birth year around 1831. His age and location suggest he could be a son or nephew of Polly’s, separated from the Lee individuals who remained in Prince George’s County. Polly’s escape to Anne Arundel County may have been an attempt to reunite with children and kin who had been separated from her in an earlier sale or division of property.

Source: U.S. Geological Survey, “Owensville, MD” Quadrangle, 1905, 1918 edition.

weaving the kinship tapestry

The convergence of genetic evidence and meticulously researched historical records allows for the reconstruction of a probable kinship connection linking Maria Matthews and Washington Lee. The shared 62 centimorgans (cM) between their descendants provides a genetic foundation, supporting the documentary trail that places Maria as the daughter of Peter Lee. Given Polly’s documented status as Peter’s wife, her determined self-liberation to be with him, and Washington’s enslavement on a Macgill estate geographically tied to Polly’s post-escape movements, the evidence strongly suggests Washington Lee was a relative of Peter Lee and Polly. This case illustrates how DNA analysis, combined with a deep examination of fragmented historical records, can contribute to understanding kinship networks that were systematically disrupted and obscured by chattel slavery. It underscores the enduring impact of the institution on individuals and their descendants, and the vital role of persistent research in revealing these crucial connections.