Known Information

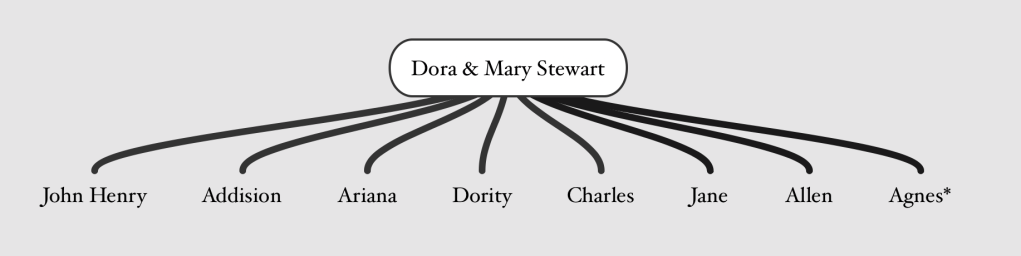

Thomas, James, John, and Mary Ellen Reeder were enslaved by Edward S Abell; he listed their names on the enumerated list submitted to the Maryland Commission of “Slave Statistics” in hopes of federal compensation in 1867. He submitted the list as guardian of Sarah and George L Smith.

He documented that they left with the Union Army on the list. He recorded that Thomas left first, in Sept 1862, and that this siblings left in Oct 1863.

1860

Edward S Abell, Enslaver

In 1860, Edward S Abell was recorded in the census as living in the neighborhood of St. Inigioes with real estate valued at $10,000 and personal estate valued at $15,000. He was married to Ann M. Crane (widow of Lewis Smith), the mother of George L and Sarah S Smith, his wards.

The July 22 1866 edition of the St Mary’s Gazette lists the expenses of the Commissioners for St. Mary’s County and demonstrates Abell’s connection with privilege and power: he was a judge, a trustee for the Poor House and a commissioner on the School Board.

In 1858, Abell advertised for sale a tract of land containing 140 acres near Cedar Point; the tract included the improvements of a dwelling, kitchen, barn, stables, and quarters.

Map shows District 1 of St. Mary’s County. St. Inigoes PO is in the north half of the District

Hired Out

Abell was required, as guardian to the Smith children, to make accounts to the court for monies received and spent on behalf the children.

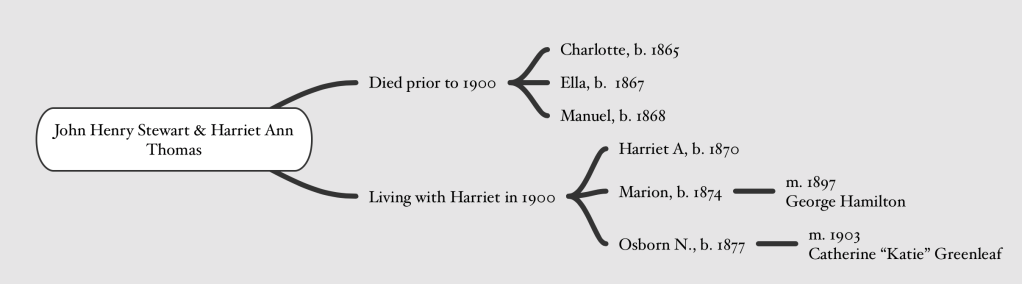

In 1864, Abell submitted his “6th Account” for George L Smith and for Sarah Smith. In this account, he recorded the profit received from hiring out John Reeder in 1862.

The account does not specify to whom Abell hired out the Reeder children. Abell was able to command a higher price for the male Reeders, James and Thomas ($55), than Mary Ellen ($15).

The economy in St. Mary’s County, while originally based on tobacco, had changed in the antebellum years to also include wheat and therefore milling. Indeed, Thomas Reeder (Sr.), father of the Reeder children, had been enslaved by James L. Foxwell who advertised his new “Foxwell Wheat” in the newspapers.

chroniclingamerica.loc.gov

The geography of St. Mary’s County, i.e., a peninsula situated between the Chesapeake Bay and tidal Potomac River, meant that the maritime industry was also crucial to the economy, including coastal trade and transport as well as fishing and oystering. The men may well have been hired out to a fishery or oysterman. “There is a great deal of evidence that slaved worked seine nets, particularly during spawning runs, and tonged for oysters.” (Marks, 543)

Mary Ellen, due to her gender and race, was likely hired out as a cook, laundrywoman, or domestic servant. As “skilled labor” typically fetched higher rates than “unskilled labor”, it suggests that Mary Ellen was not viewed as “a skilled laborer” by Abell and those who hired her.

1862-1863 Escape

September 1862

Thomas Reeder, age 21, escaped Sunday, 14 Sept 1862. How Thomas Reeder escaped is unknown.

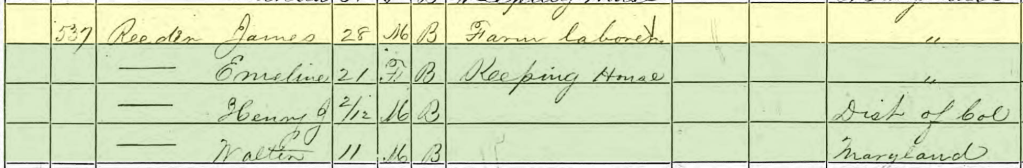

On October 2, 1862, the St. Mary’s Beacon reported that “There has been quite a stampede of ‘contrabands’ from our county during the past two weeks…Most likely, emissaries are amongst us, either itinerant or local, and that gunboats are employed to facilitate escape. Quite a number are reported to be harbored at Point Lookout, by Federal authority and all efforts to recover them have proven futile.” [Chronicling America | loc.gov]

In the same edition of the St. Mary Beacon, the Provost Marshal for St. Mary’s County warned it’s [white] citizens “to lock at night or otherwise secure their BOATS and CANOES of all kinds against probable or possible use of them by deserters,…,fugitive slaves from Maryland”

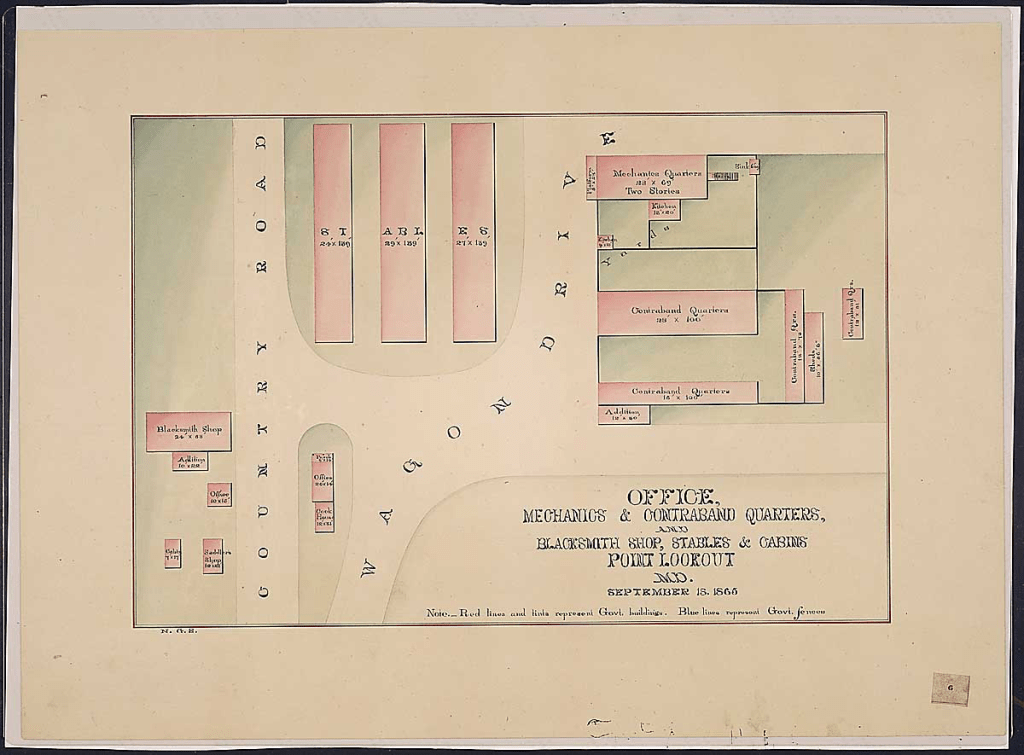

Thomas Reeder may have travelled to Point Lookout, located on the southern most tip of the peninsula where the federal government had established a hospital on the former grounds of a resort. Abby Hopper Gibbons, a Quaker nurse working at the hospital described in her diary:

“On the same day [Sept 1862], nineteen men and five women came–refugees; and the day after, fourteen men and five women, with some little children. They are making the most of the moonlight nights.”

Abby Hopper Gibbons, p. 373

In the early days of the hospital, the federal authorities were not prepared to provide a safe haven for the refugees who used the hospital as a means of escape from bondage. Gibbons wrote that at the beginning men and women who escaped to the hospital were returned to their enslavers if the enslavers swore an oath of loyalty to the Union (in contrast to the St. Mary’s Beacon article). [Gibbons, page 367]

In mid-1862, the hospital had no means to house the contrabands and a nurse, Sophronia Bucklin, who visited the camp on the edge of the hospital described their shelter in the pine trees north of the hospital:

Amidst the dense, dark pines they burrowed like beasts of the field in half-subterranean dens. A hole from three to four feet deep was dug by them in the black soil, and roofed over with boards, on which turf was closely packed. An opening, which admitted them on their hands and feet, and one for the escape of the smoke, which went up from an exceedingly primitive fireplace, were the only vents for the impure air, and the only openings for light. In these dens men, women and children burrowed all winter

Bucklin, 84

As time passed though, Gibbons described getting more and more refugees on the boats that went north to Washington. It is possible that Thomas was able to get aboard one of the boats to the District.

October 1863

James Reeder, age 19, escaped Saturday, October 17. His brother and sister, John, age 30 and Mary Ellen, age 16, escaped a week and a half later, on Wednesday October 28. Like Thomas, it is likely they made to Point Lookout in search of a boat that would take them north to the District and freedom.

By 1863, the hospital had built barracks for the refugees. The quarters were built near the blacksmith shop and the mechanics quarters, signifying how the hospital and the US Army changed their view of refugees; no longer property to be returned to the enslaver, rather a source of labor for the Army.

Sources

Marks, Bayly E. “Skilled Blacks in Antebellum St. Mary’s County, Maryland.” The Journal of Southern History, vol. 53, no. 4, 1987, pp. 537–64, https://doi.org/10.2307/2208774. Accessed 5 Apr. 2022.

Gibbons, Abby Hopper. Life of Abby Hopper Gibbons: Told Chiefly Through Her Correspondence. United Kingdom, G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1896. accessed from Google Books

Bucklin, Sophronia E.. In Hospital and Camp: A Woman’s Record of Thrilling Incidents Among the Wounded in the Late War. United States, J.E. Potter, 1869. accessed from Google Books