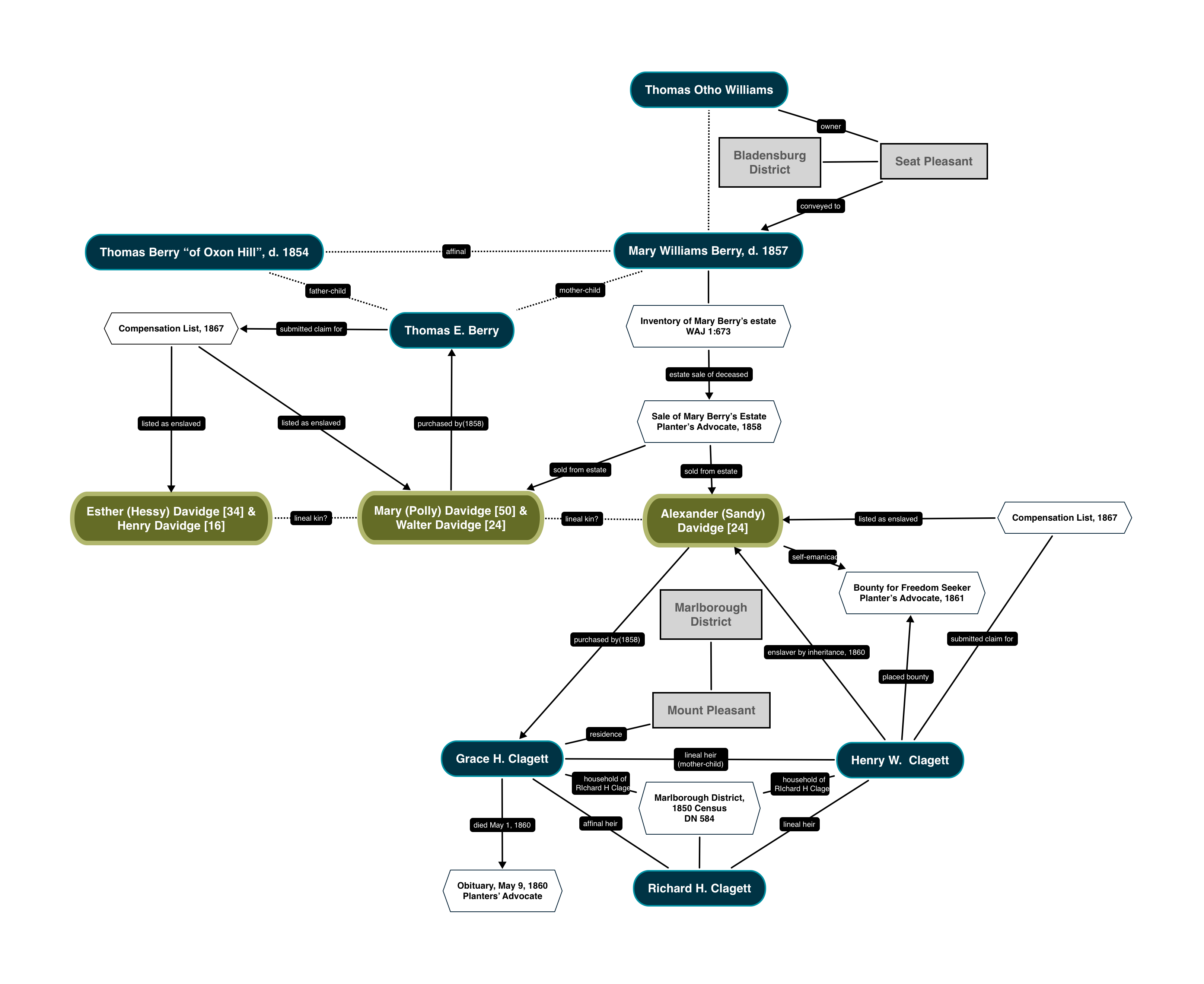

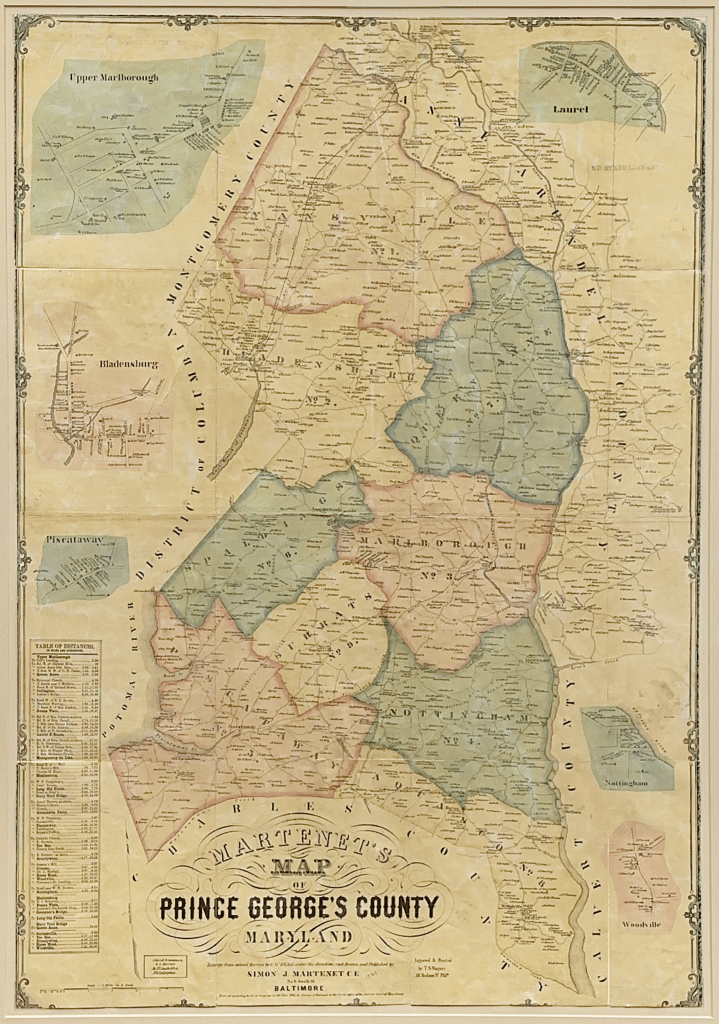

Source: Base map by S. Martenet (1861); overlay data from M-NCPPC (2010).

introduction: a story rooted in place

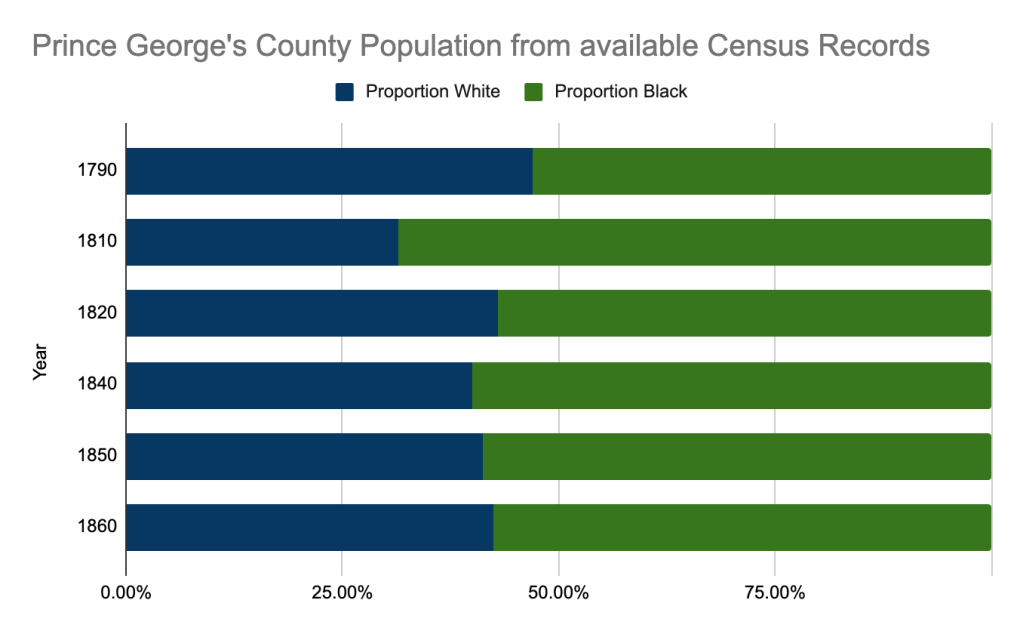

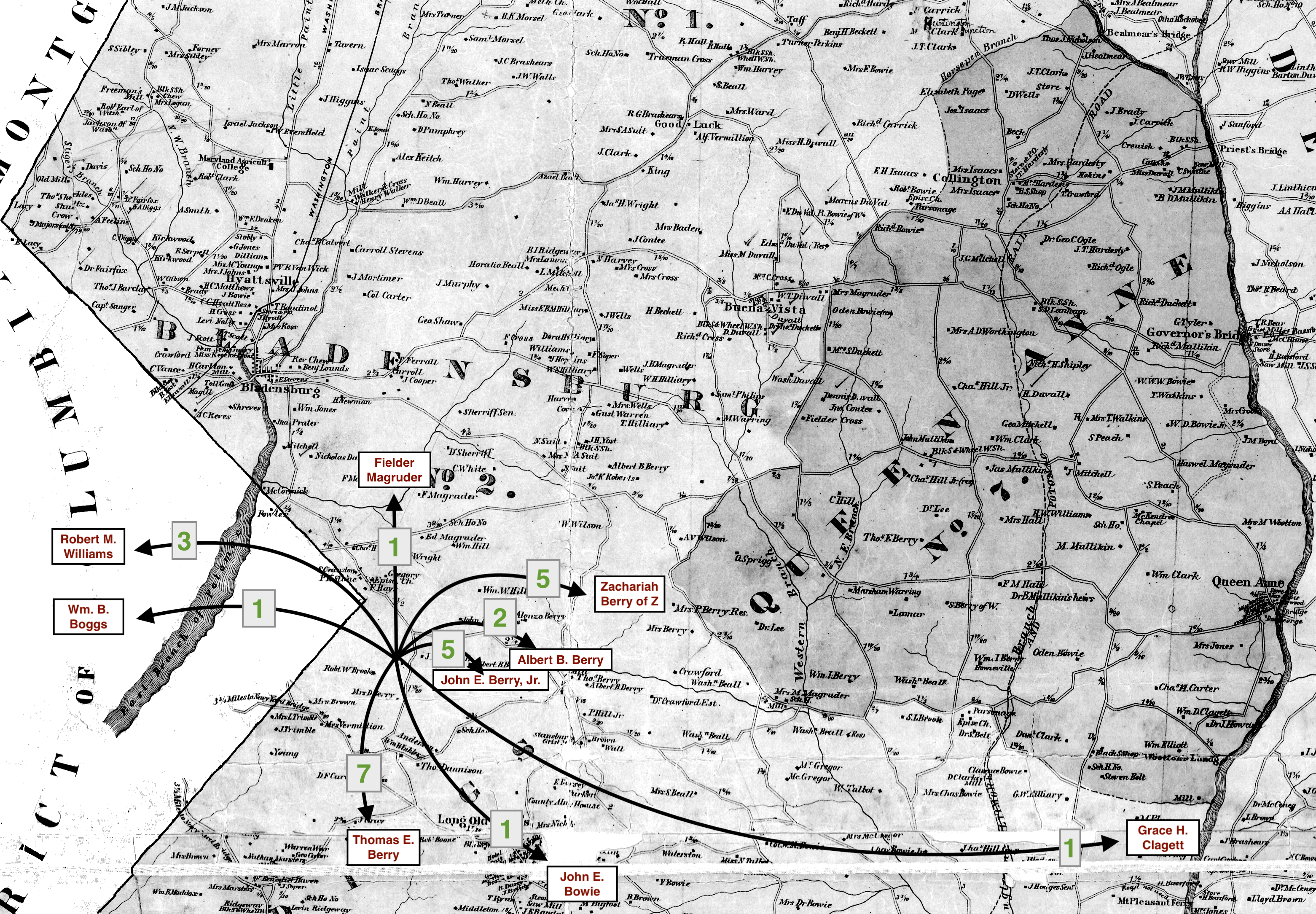

Antebellum Prince George’s County was a divided world. The world of planters and estates was visible through the creation of Martenet’s Map of Prince George’s County, which documented the landowners and their proximity to seats of power (Upper Marlborough, county seat, as well as the District of Columbia, the nation’s capital) and to transporation routes (the railways, the rivers, the roads). The single black dot on Martenet’s map indicating landowners obscured the outbuildings, quarters, and fields occupied by the enslaved and free Black population of Prince George’s County.

The historical record documents two versions of Alexander (Sandy) Davidge. In one, he is a financial asset, a name on a legal claim filed by his former enslaver six years later. In the other, he is a man of decisive action, self-liberating from a Maryland plantation in the winter of 1861. The gulf between these two records defines not only his story but the divided world of Antebellum Prince George’s County itself, where the landscape of power shown on official maps obscured the complex lives of the enslaved.

the berrys: a multi-district sphere of control

In 1828, Thomas Berry appears in the tax list for Prince George’s county as owning 1300+ acres called Oxon Hill Manor and 650 acres called Seat Pleasant. Berry acquired these acres through a conveyance from his father, Zachariah Berry “of Concord” and through his 1815 marriage to Mary Williams, the would-be heir of Thomas Otho Williams, d. 1818. Their son, Thomas E. Berry would own property in Queen Anne District in the Partnership Neighborhood, in addition to managing his father’s Oxon Hill Manor estate. Other branches of the Berry family would own land in Bladensburg, including the estates of Concord, Graden, and Independence demonstrating the scope of control the Berry network had on the lives of the enslaved people.

Alexander (Sandy) Davidge labored for Mary Berry at Seat Pleasant. He was first named in an 1847 deed of separation between Mary Berry and her husband, Thomas Berry. Due to “unhappy differences” that have arisen between the husband and wife. In exchange for the property settlement, Mary gives up any future claim to dower rights on Thomas Berry’s separate estate. Thomas and Mary Berry transfer a significant amount of property to the trustee, Elisha W. Williams, for the sole benefit of Mary Berry. This property includes:

- Land, specifically part of a tract called “Seat Pleasant,” which is explicitly identified as having “came to the said Mary Berry as one of the heirs of her deceased Father [Thos. O. Williams]”.

- Livestock, including hogs, sheep, cows, and horses.

- Farm equipment and crops, including “thirty hogsheads of tobacco”.

- A community of enslaved people, who are listed by name.

Among them, is “Sandy”.

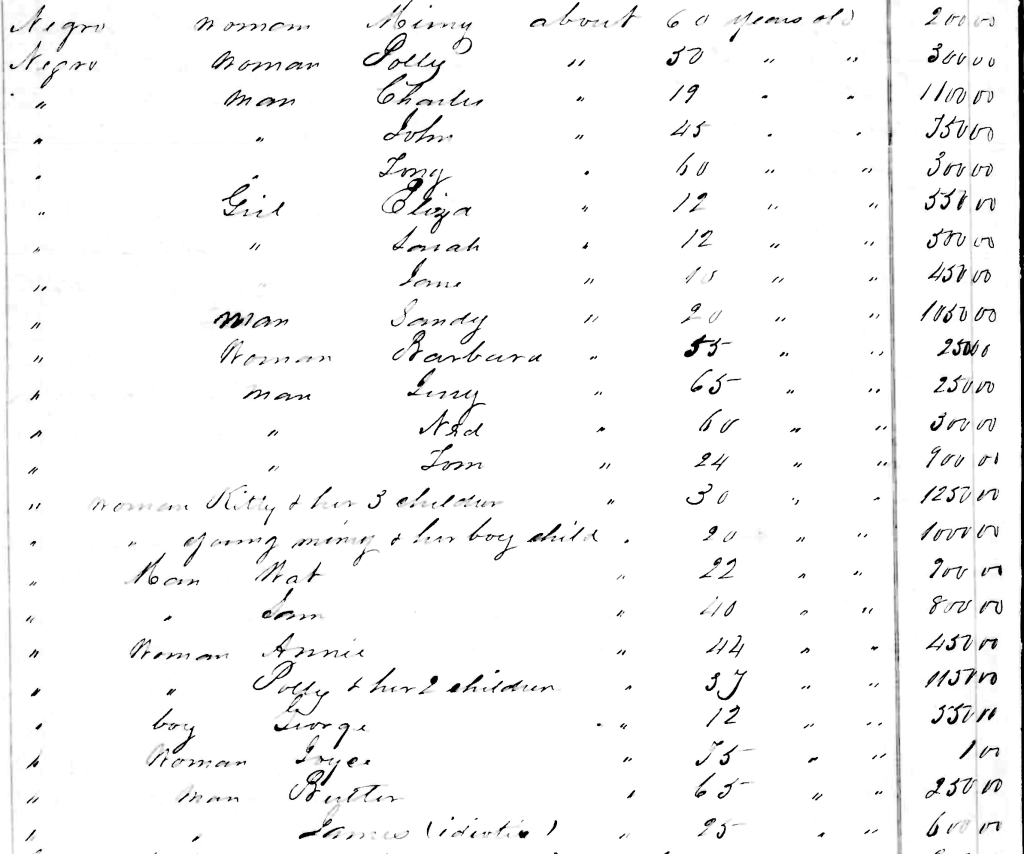

The list minimally names relationships between members of the community forced to work in the tobacco fields, to care for the livestock and to tend to the farm equipment. From the list, there are some spouses and some children — and other relationships (siblings, cousins, etc.) are ignored and invisible. While the deed explicitly names the wives of Jerry and Sam Butler and the children of Kitty and Caroline, Sandy is listed between Thomas/Tom and Kitty, an individual seemingly untethered to any named kin in that moment.

Sandy was also listed in the inventory of Mary Berry’s estate when she died a decade later in 1857. A twenty-year old man, the appraisers assigned him an external market value of $1050. The appraiser’s commodification of Sandy rested on their value of his ability to provide physical labor. Charles was nineteen years old, and externally appraised for $1100 while Walter (Wat) was twenty-two years old, and externally appraised for $900.

Like the deed of separation, Sandy, Walter, and the others are untethered in their relationships. Unlike other other inventories who adhere to one of two organizational patterns ( by gender and chronological age, or by adult males, and mother-child groupings), the list of Mary Berry’s estate includes the names of those she enslaved in a non-recognized order. Mimey and Polly, two elderly woman, head the list, despite the inclusion of other elderly men (Tony and Ned); Eliza, Sarah, Jane, pre-adolescent girls are listed immediately following Tony without a mother, suggesting a possible loss prior to the inventory. Alternatively, the list could be organized by sphere of work, with the first half (headed by elderly woman) representing those who labored in the household, while the second half representing the field hands.

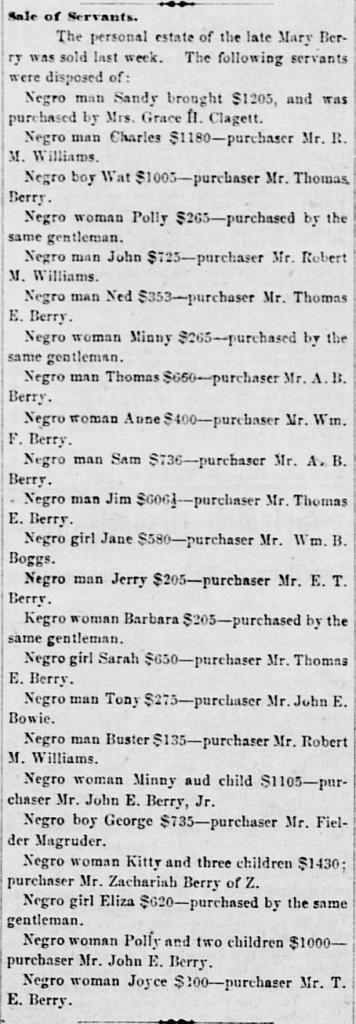

The death of Mary Berry, the mistress of Seat Pleasant, and the appraiser cataloguing her furniture, agricultural implements and enslaved community precipitated precipitated a forceful fragmentation of that community, initiating an unasked-for migration that scattered kin across the distinct agricultural landscapes of Prince George’s County.

A few months after her death, the Planters’ Advocate advertised the sale of Mary Berry’s estates, both real and personal:

Transcription of Estate Sale Advertisement

A VALUABLE ESTATE FOR SALE, Containing Eight Hundred and Twenty-Four and One-Fourth Acres.

BY virtue of a decree of the Circuit Court for Prince George’s county, sitting as a Court of Equity, the subscriber, as Trustee, will offer at public sale, on the premises, ON FRIDAY, the 11th day of March next, if fair, if not, the next fair day thereafter, the VALUABLE REAL ESTATE of the late Mary Berry, containing, by a recent survey, EIGHT HUNDRED AND TWENTY-FOUR ACRES AND ONE-FOURTH OF AN ACRE.

This estate is situated in Prince George’s County, very near the District line, commanding a beautiful view of the Capitol and a portion of Washington City.

The improvements are a good comfortable Dwelling House, KITCHEN, and all the necessary OUT-HOUSES, including STABLES and CARRIAGE HOUSE. The Farm Houses consist of four or five TOBACCO HOUSES, in a good state of repair, and affords room enough to house fifty thousand pounds of tobacco.

This farm consists of a soil well adapted to the growth of the finest quality of Tobacco and all the other staple crops grown in the county. Has a sufficiency of MEADOW LAND, some of it TIMBER, and also an abundance of WOOD and TIMBER.

This land, from its proximity to Washington City, affords a rare chance for speculation and a profitable investment. Portions of it might be profitably cultivated in Fruits and Vegetables, in addition to making a Tobacco Farm.

THE TERMS OF SALE, AS PRESCRIBED BY DECREE, ARE: A cash payment of one thousand dollars to be made on the day of sale, and the balance of the purchase money to be paid in three equal instalments, in twelve, eighteen, and twenty-four months; the whole purchase money to be secured by the bond of the purchaser, with security to be approved by the Trustee, and to bear interest from the day of sale. Upon the payment of the purchase money and interest, the Trustee is authorized by the decree to convey the land to the purchaser in fee simple, and all the right, title, claim and interest of the parties to the cause, and of all those claiming by, through or under them or either of them.

Possession of the property will be delivered as soon as the terms of sale are complied with.

Those wishing to purchase are invited to view the premises, and are referred to A. B. BERRY, Esq., who owns the adjoining farm.

C. C. MAGRUDER, Trustee. Upper Marlboro’, Feb. 16, 1859—ts

Transcription of Sale of “Servants”

Sale of Servants.

The personal estate of the late Mary Berry was sold last week. The following servants were disposed of:

Negro man Sandy brought $1205, and was purchased by Mrs. Grace H. Clagett. Negro man Charles $1180—purchaser Mr. R. M. Williams. Negro boy Wat $1005—purchaser Mr. Thomas. Berry. Negro woman Polly $265—purchased by the same gentleman. Negro man John $725—purchaser Mr. Robert M. Williams. Negro man Ned $355—purchaser Mr. Thomas E. Berry. Negro woman Minny $265—purchased by the same gentleman. Negro man Thomas $650—purchaser Mr. A. B. Berry. Negro woman Anne $400—purchaser Mr. Wm. F. Berry. Negro man Sam $736—purchaser Mr. A. B. Berry. Negro man Jim $606—purchaser Mr. Thomas E. Berry. Negro girl Jane $580—purchaser Mr. Wm. B. Boggs. Negro man Jerry $205—purchaser Mr. E. T. Berry. Negro woman Barbara $205—purchaser by the same gentleman. Negro girl Sarah $650—purchaser Mr. Thomas E. Berry. Negro man Tony $275—purchaser Mr. John E. Bowie. Negro man Buster $135—purchaser Mr. Robert M. Williams. Negro woman Minny and child $1105—purchaser Mr. John E. Berry, Jr. Negro boy George $735—purchaser Mr. Fielder Magruder. Negro woman Kitty and three children $1430; purchaser Mr. Zachariah Berry of Z. Negro girl Eliza $620—purchased by the same gentleman. Negro woman Polly and two children $1000—purchaser Mr. John E. Berry. Negro woman Joyce $100—purchaser Mr. T. E. Berry.

At the 1858 estate sale, the community was fragmented; a twenty-year-old Sandy was sold for $1205, while his peers Charles (19) and Walter (22) brought $1180 and $1005 respectively.

the clagetts: the widow’s residence

Sandy was purchased by Grace H. Clagett, a widow who managed her assets from her parents’ residence of Mount Pleasant. The daughter of Col. Henry Waring and Sarah Harrison, she had married Dr. Richard H. Clagett who died in the early 1850s, leaving her with her son, Henry W. Clagett. She managed at least two farms prior to her own death in 1860.

In the fall and winter of 1857, she advertised in the Planters’ Advocate for the hire of additional field hands before purchasing Sandy at the sale of Mary Berry’s estate.

Despite advertising for two additional men, she only purchased Sandy from Mary Berry’s estate, which meant that Sandy arrived alone and without the comfort of a social network at Mount Pleasant. Any family he had lived with Seat Pleasant had been sent to work at other plantations and estates.

Sandy was taken by the Clagett from a farm near the District, near the roads that led to the bustle of the City of Washington. While working the fields on Seat Pleasant, he would have seen wagons and carts traveling into town filled with produce, with livestock tied to back for butchers. He would have seen stagecoaches and horseback riders traveling with the mail and the guests who would stay at the Hotels on Pennsylvania Ave. When he was forced from Seat Pleasant to Mount Pleasant, the landscape would have changed to a waterfront, where traffic was directed to the steamboats and the small boats that traveled the silting Patuxent. Instead of gentlemen headed to the City of Washington for national politics and markets, he would have seen gentlemen headed to Upper Marlborough, the county seat for estate sales, courthouse dealings, and horse races.

Two years after purchasing Sandy, Grace died on May 1, 1860 after a long illness at her parent’s estate, Mount Pleasant. Without a will and inventory, it is presumed her real and personal estate, including Sandy, was conveyed to Henry W. Clagett, her son. The death of his second enslaver most likely stirred up memories of the last time his enslaver died, with the sale of him and his new community on the auction block. Moreover, his new enslaver, Henry W Clagett, was a young bachelor who had yet to “settle down”. Away at Georgetown for college, his visits home may have been stories of drinking and gambling and other college escapades, which often meant money owed to creditors and debts to be covered by the sale of a “valuable field hand”. This recurring pattern of instability, where his life was subject to the whims of inheritance, now placed his future in the hands of a young, unmarried man, Henry W. Clagett. The prospect of yet another disruption may have been the final catalyst for his decision to escape.

the landscape of Escape

Against this backdop, Alexander (Sandy) Davidge self-liberated himself from Clagett’s estate near Mount Pleasant wearing a brown frock coat and dark hat with black pantaloons the day after Christmas. The week between Christmas and New Years was one of anticipation of separation as enslavers hired out or sold individuals, separating them from the comfort of community within a cold landscape bereft of warmth.

Clagett supposed that Alexander was making his way to family members at Mrs. Thomas E. Berry’s near Long Old Fields, or acquaintances near Bladensburg, suggesting that Sandy was going back to the neighborhood from which he had been extracted, and back to a known community.

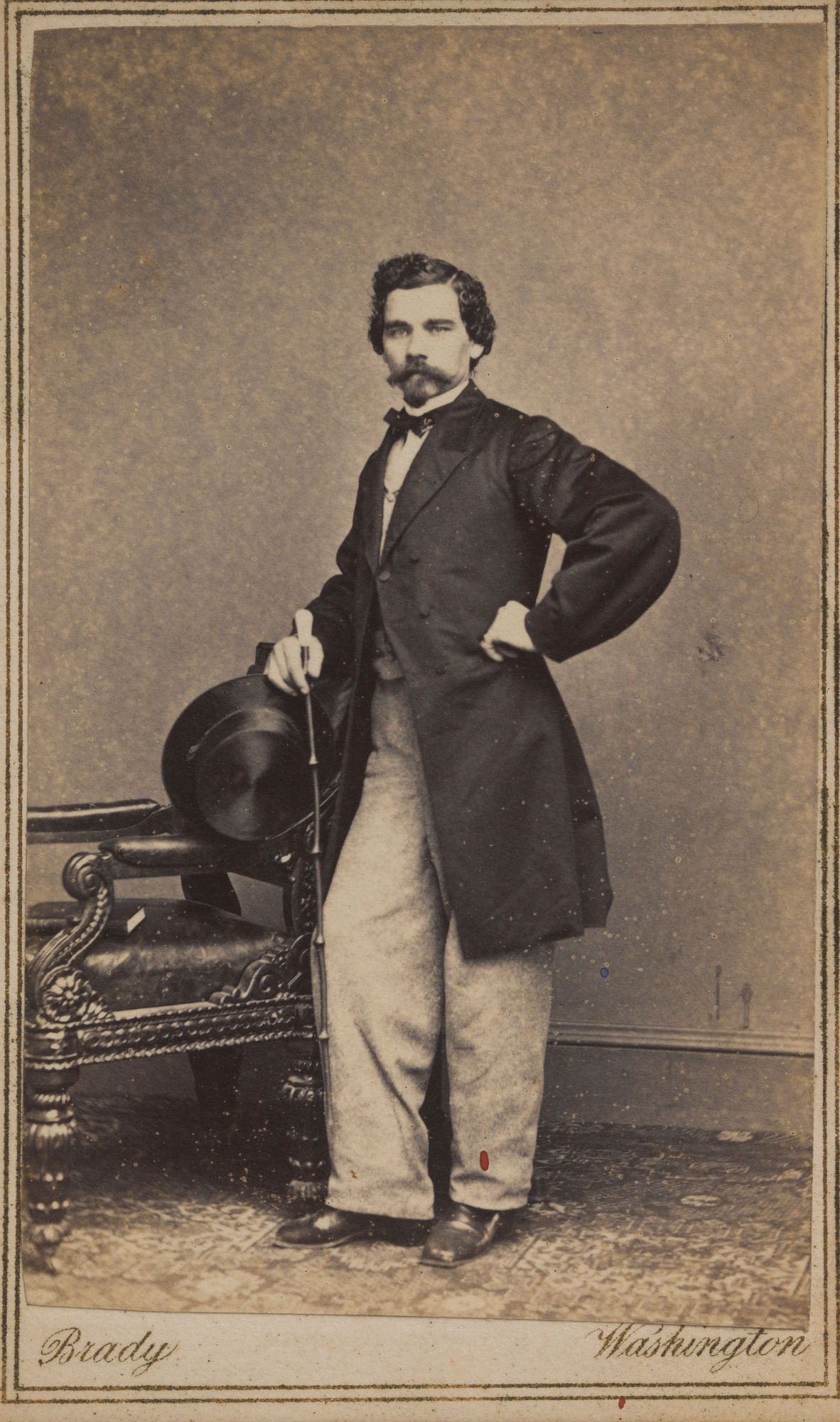

The portrait of John Mulvaney, 1863 provides a visual possibility of what Alexander Davadge wore on his escape to freedom. Choosing a frock coat (more formal than everyday work wear), it would allow Sandy to blend into the crowds moving through the streets of the City. The frock coat would also provide a layer of warmth as he left in the midst of winter.

Transcription of Bounty for Sandy Davadge

$100 Reward. RAN AWAY from the subscriber, living near Upper Marlborough, on Wednesday, the 26th ultimo, a negro man SANDY, who calls himself

SANDY DAVADGE.

Sandy is about five feet nine or ten inches high; is of a dark complexion; has a full suit of hair and a fine set of teeth; is quick when spoken to, and very polite. He had on when he left home a pair of black pantaloons, brown frock coat and a dark hat. He has relations living at Mrs. Thomas E. Berry’s place, near the Long Old Fields, and also acquaintances in Bladensburg.

I will give the above reward for his apprehension, if taken out of the State of Maryland, and Fifty Dollars if taken in the State—in either case he must be brought home or secured in jail, so that I get him again.

HENRY W. CLAGETT. January 2, 1861—tf

As he traveled the roads, turnpikes and trails into the District where he could make for a “Free State”, he would have been wary of slave patrols, set up to control his movement through the landscape of tobacco fields and orchards. Some were more formally organized and others were suspicious planters and planters’ sons, hiding behind bushes to capture the family fleeing for freedom.

Transcription of “Running Off Negroes”

RUNNING OFF NEGROES.—The Pr. Georgian of last Friday says:

This day fortnight ago, Messrs. Francis M. Bowie and John E. Bowie, Jr., having some cause for suspicion of some such occurrence, posted themselves in a suitable position and captured a negro who was carrying off, in the dead of night, a negro woman and her two children, the property of the first named gentleman. They were in a covered wagon. The negro is a slave of a lady residing in Montgomery, and the wagon was borrowed from an officer at the Observatory, for another purpose. The prisoner was brought here the day following and indicted by the Grand Jury. He is now in jail.

Transcription of “Appointment of a Patrol in Alexandria County”

APPOINTMENT OF A PATROL IN ALEXANDRIA COUNTY. The Gazette says: “The County Court of this county at its last term, appointed a patrol for the country portion of this county. The appointment was made under the following provision of the Code of Virginia: “The county court of each county may, when necessary, appoint for a term not exceeding three months, one or more patrols, consisting of an officer either commissioned or non-commissioned, who shall be captain of patrol and so many privates as it may think requisite, to patrol and visit within such bounds as the court may prescribe, as often as it shall require, all negro quarters and other places suspected of having therein unlawful assemblies, or such slaves as may stroll from one plantation to another without permission.”

The following gentlemen were named as the patrol:—Wm. J. Garey, Captain; S. Burch, jr., John Marcey, George Marcey, Elijah Burch, Thos. Thompson, Samuel Marcey and Chas. W. Payne, privates.

It is the duty of this patrol to visit all parts of the county, at least once a week; to break up all unlawful assemblies and arrest negroes violating the law. The members of patrol failing to perform duty, are subject to a fine of five dollars, and when on duty the captain is entitled to one dollar and each private to 75 cents for each twelve hours service.

Transcription of “Affairs in the St. Mary’s County, MD”

AFFAIRS IN ST. MARY’S COUNTY, MD.—Runaway Slaves—Patrols called out—The Leonardtown Beacon of Thursday has the following in relation to affairs in that neighborhood:

Three negro men, representing themselves as runaway slaves from Virginia, were arrested and lodged in our county jail on Tuesday last. They crossed the Potomac in a canoe, and were arrested by private citizens and handed over to the sheriff. They were young, likely negroes, and stated that “they had heard a great deal of talk about Maryland, and came over to see if the truth had been told them.” They represent their masters to have been absent from home at the time they determined upon their tour of investigation. We learned on Tuesday last that there had been many recent cases of runaway in this county. Would it not be well to reorganize the system of patrol that proved so efficient here last winter?

Since the abandonment of the patrol, the negroes have pretty generally fallen into their old night-prowling habits and we hear of several who have ran away from their owners and are now lurking in the county. The patrol force has never been legally disbanded, and are consequently at liberty to go upon duty whenever they may think the public interest requires it. We believe that it requires it now, and we recommend that the force in the different districts proceed at once to make an organization and go upon duty and remain upon duty while the present excitement through the country continues to exist. We hope to hear that the patrol force are in active operation in every district of the county by Saturday next.

During the winter of 1861, Southern Maryland was a region of high tension and strategic importance in the Civil War. As a border state with strong secessionist sympathies, particularly in counties like Prince George’s and Charles, the area was under a heavy Union military occupation designed to secure its loyalty and protect the perimeter of Washington, D.C.

This resulted in a significant and visible presence of Union troops guarding crucial infrastructure, such as railroads and key roads. The Potomac River became an active military frontier due to the “Potomac Blockade,” where Confederate batteries on the Virginia side frequently exchanged fire with Union forces in Maryland, disrupting river traffic. This created a volatile atmosphere for refugees from slavery who sought to navigate both troops and patrols on the road to freedom.

disappearance from the Map

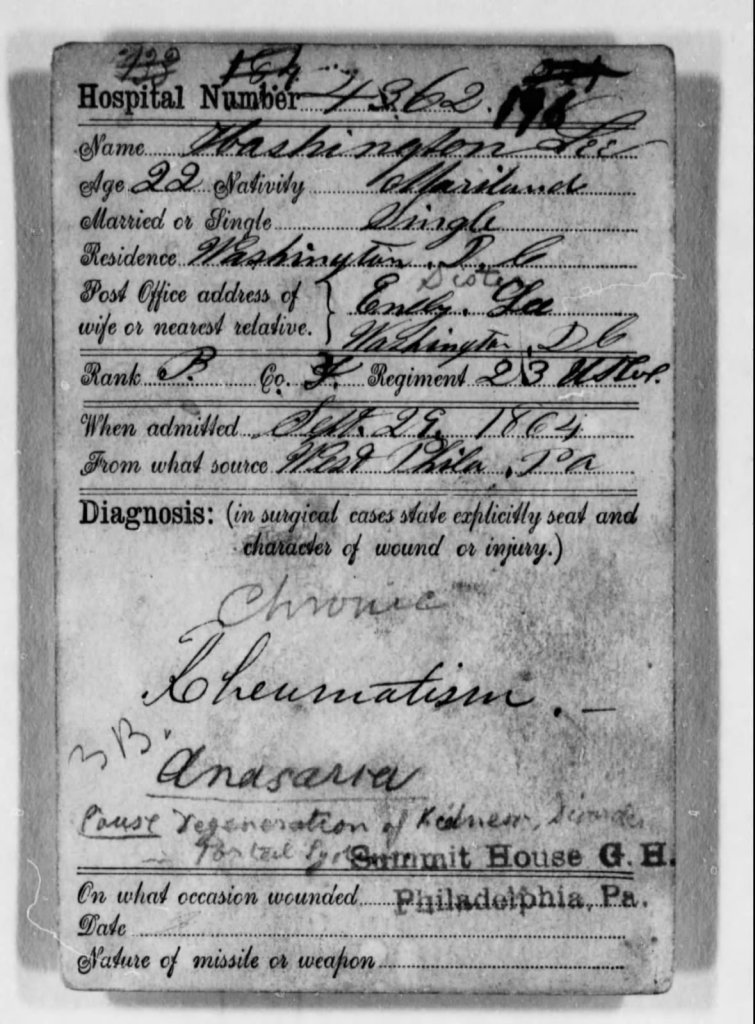

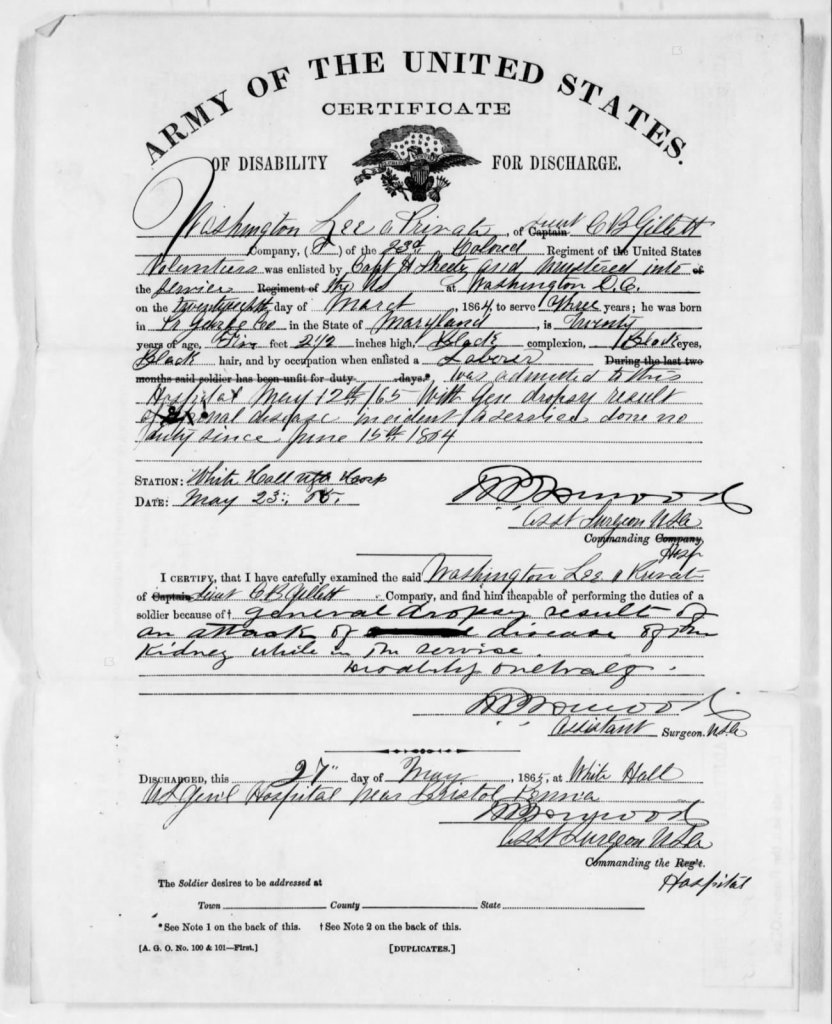

After 1861, Alexander (Sandy) Davidge vanishes from the known map.

In 1867, the former slaveholders submitted claims for compensation for the people emancipated by the November 1864 Constitution of Maryland. Henry W. Clagett was one of the enslavers who submitted a claim. On his list was “Sandy Davidge, age 24”, his name one of 54 people enslaved by Clagett. Clagett, by placing him on the list, is stating on oath Davidge was “in his possession” on Nov 1, 1864, after his escape to freedom. There are no records to clarify if Clagett had recaptured him or if he submitted a fraudulent claim.

Alexander’s family, the ones enslaved by Mrs. Thomas E. Berry near Long Old Fields, appears on a list submitted by “Thomas Berry”: Polly (Mary) Davidge, age 50 and WalterDavidge, age 24, purchased from Mary Berry’s estate and likely Alexander’s mother and brother, as well as Esther (Hessy) Davidge, age 34, and Henry Davidge, age 16.

Clagett’s compensation claim in 1867 is an attempt to place him back on the Marlborough plantation ledger, but his physical body is gone. His final destination, his geography of freedom, remains unknown.

Martenet, Simon J. Martenet’s Map of Prince George’s County Maryland. Philadelphia: J.L. Smith, 1861. https://www.mdcourts.gov/lawlib/research/special-collections-room/map-of-prince-georges-county-1861.

The Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission. African-American Historic and Cultural Resources in Prince George’s County, Maryland. Upper Marlboro, MD: The Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission, 2010. https://www.mncppcapps.org/planning/publications/pdfs/206/6%20Agriculture%20and%20Slavery%2009.pdf.