The July 4, 1860, issue of the Planters’ Advocate and Southern Maryland Advertiser presented its readers with a portrait of a society celebrating freedom while actively profiting from its denial. One column announced a Fourth of July celebration at the Brick Church (St. Barnabas) in the Wootton’s Landing neighborhood. There, Gonsalvo Clagett was scheduled to read the Declaration of Independence, and the lawyer and enslaver Daniel Clarke would deliver an oration.

Source: Planters’ Advocate and Southern Maryland Advertiser, 4 July 1860. Maryland State Archives, Special Collections (Digital Images).

This was not an isolated event. The same issue reported a “Celebration at Bladensburg,” where local militias used the national holiday for a display of military readiness. The “Vansville Rangers,” led by Captain Snowden, and the visiting “Severn (A. A. County) Guards” under Capt. Setros were to participate. These local militias, which had been forming and drilling in anticipation of the coming war, gathered in their military finery to march and listen to speeches before dining at Suit’s Hotel. Their very presence was a show of force, a demonstration of their commitment to preserving their way of life through armed strength.

Source: Planters’ Advocate and Southern Maryland Advertiser, 4 July 1860. Maryland State Archives, Special Collections (Digital Images).

Advertisements throughout the paper catered to this class to project the status they were prepared to defend. These advertisements offered “FASHIONABLE CARRIAGES” from M. McDermott’s manufactory and the “FINEST STOCK OF CLOTHING” from J. M. McCamly, & Co. while Chas. H. Lane offered hats, caps, and gentlemen’s furnishing goods, “a superior and fashionable stock” for the enslaver class to display its status.

Advertisement for Washington D.C. stores catering to the enslaver class. Fashionable goods served as public symbols of the status and wealth generated by the forced labor of enslaved people.

Source: Planters’ Advocate and Southern Maryland Advertiser, 4 July 1860. Maryland State Archives, Special Collections (Digital Images).

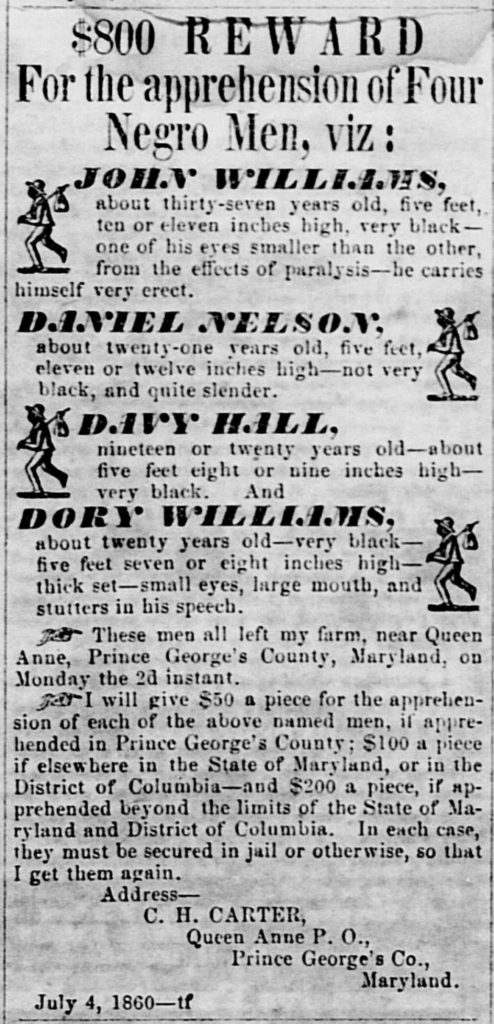

Juxtaposed with these notices of celebration and shopping was another, more sobering advertisement: an “$800 REWARD” placed by C. H. Carter from the Queen Anne Post Office. Carter was the nephew of Robert E. Lee, and owner of the 800 acre estate “Goodwood” on the land tract Cool Spring Manor. The ad, dated July 4th, sought the capture and return of four men who had escaped his authority two days prior.

Source: Planters’ Advocate and Southern Maryland Advertiser, 4 July 1860. Maryland State Archives, Special Collections (Digital Images).

The notice details the individuals, transforming them from a mere statistic into people:

- John Williams, about 37, who carried himself “very erect” despite the effects of paralysis in one eye.

- Daniel Nelson, about 21 and described as “quite slender.”

- Davy Hall, 19 or 20 years old.

- Dory Williams, about 20, who was “thick set” and stuttered.

While the community’s enslavers gathered at the Brick Church to hear proclamations of liberty, C. H. Carter was leveraging the economic and legal power of the press to reclaim these four men as property. The tiered bounty—$50 for capture in Prince George’s County, rising to $200 if they were apprehended “beyond the limits of the State of Maryland and District of Columbia”—methodically calculated the monetary value of their stolen freedom.

The pages of this single newspaper issue capture the fundamental hypocrisy of American Independence. The freedom celebrated with music and speeches at the Brick Church was an abstraction underwritten by the system of chattel slavery. For John Williams, Daniel Nelson, Davy Hall, and Dory Williams, freedom was not a quotation to be read aloud but a tangible, life-threatening pursuit undertaken in defiance of the men celebrating at the church.

By July 4th, as C. H. Carter’s reward notice was being printed, John Williams, Daniel Nelson, Davy Hall, and Dory Williams had been in flight for two full days. Their journey for freedom was a calculated rejection of the world celebrating at the Brick Church. Leaving behind “Goodwood”, their primary objective would have been freedom, which may have been the free state of Pennsylvania, a perilous overland journey of nearly one hundred miles. This route required moving covertly by night, navigating unfamiliar terrain, and evading the slave patrols mobilized by Carter’s advertisement. Alternatively, they might have sought refuge within the large free Black community of Washington, D.C. to the west—a known path for freedom seekers, as anticipated by Carter’s tiered reward for their capture in the District. Whether they followed roads, trails, or used the nearby Patuxent River as a guide, every step was fraught with the risk of discovery. For these four men, Independence Day 1860 was not a day of rest and speeches, but a critical point in a life-or-death flight where capture meant a violent return to chattel slavery and success promised a precarious new beginning.