empires of Leaf and Labor

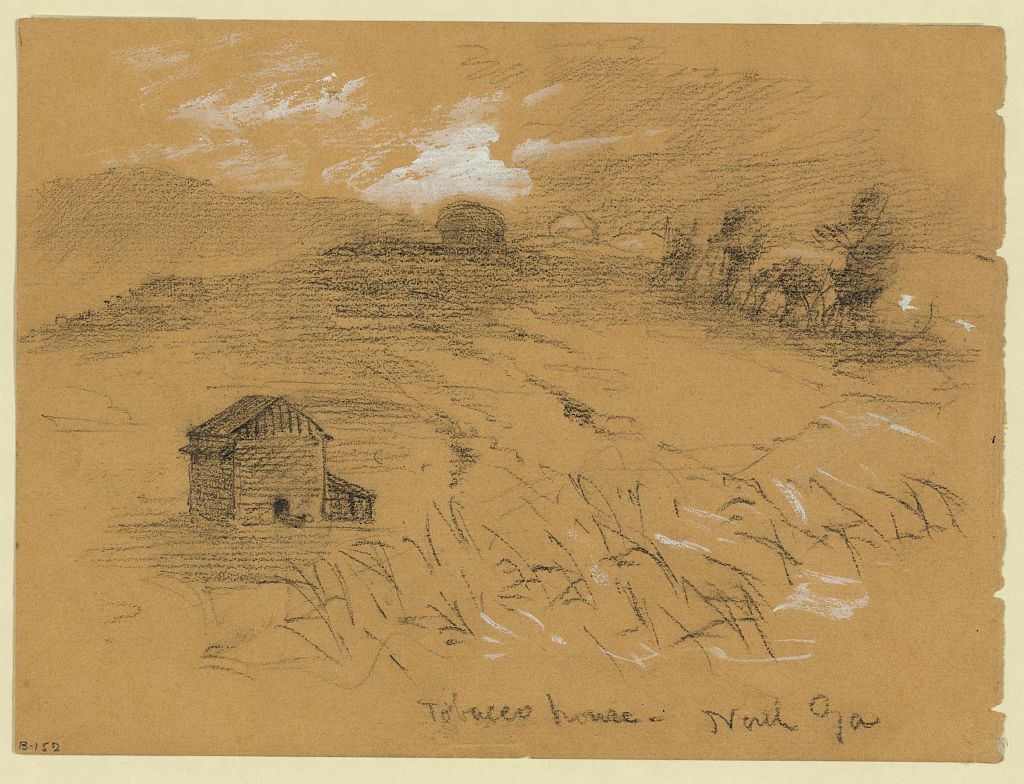

Queen Anne District was situated in the “Forest of Prince George’s County”, and a contributor to the New York Times described it as “the great tobacco region of Maryland, and probably no other territory of equal extent in America produces so much of that famous weed.” [Dec 6, 1861] This immense agricultural output depended entirely on a vast population of enslaved people, who by 1860 constituted the majority of the county’s residents. From preparing the soil and the seedbeds, to tending the transplanted seedlings, to the constant worming and topping of the plants, to the harvest where entire stalks were cut, hung to cure, and stripped of their leaves for passage to the markets, the work was tedious and back-breaking.

lord of thorpland and thomas circle

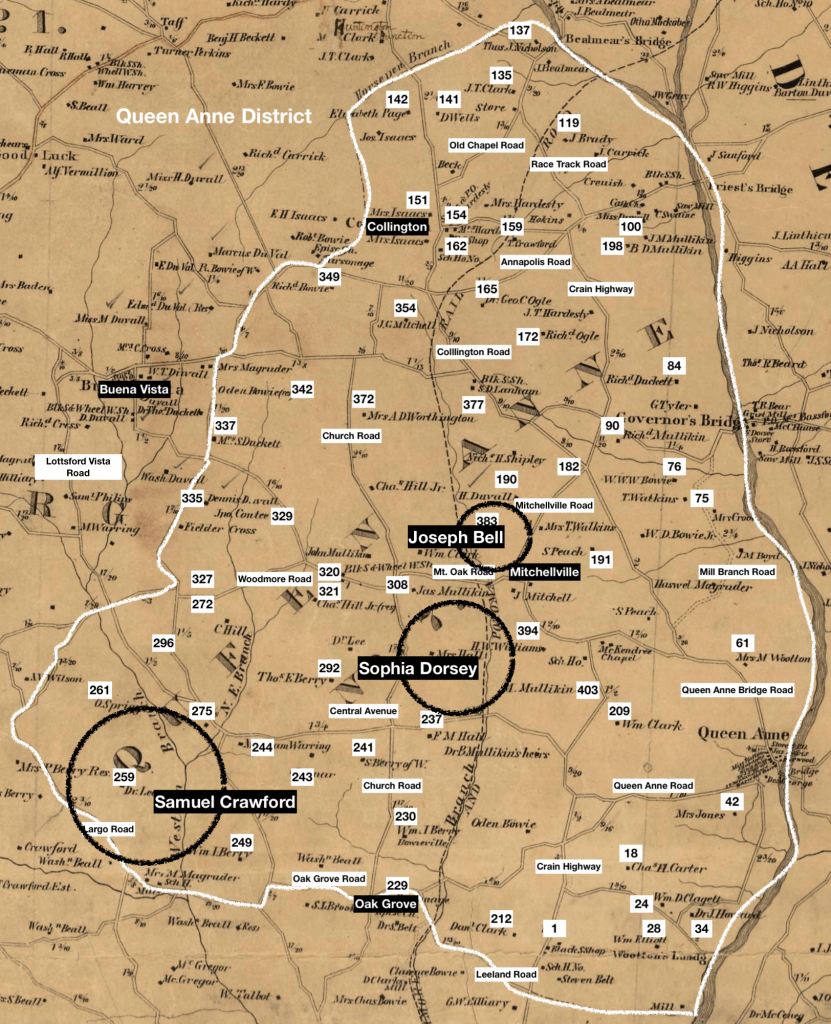

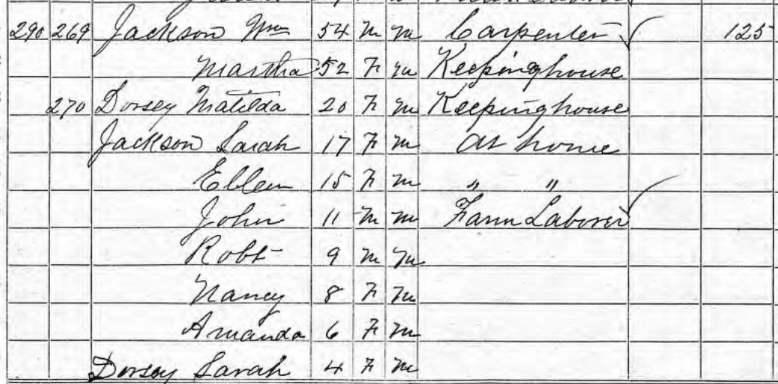

Charles Hill was a descendant of Clement Hill, who owned Compton Bassett, a large estate to the east of Upper Marlboro near Hill’s Landing. Since 1700, the Hill family had implemented strategic marriages with the Darnalls, Digges, and other prominent Catholic families, establishing their status among the elite planters. Charles Hill purchased the nearby Thorpland in the 1810s and later acquired other lands throughout Queen Anne District. By 1828, his holdings were assessed at nearly 2,000 acres. An estate of this scale, classified as a large plantation, depended on the forced labor of more than one hundred enslaved people to generate the profits necessary to sustain and expand his agricultural enterprise. In addition to his holdings in Prince George’s County, Hill was a director for the Bank of Metropolis in Washington, cementing his role as a capitalist with a fashionable city residence in Thomas Circle.

plows, prizes, and profit

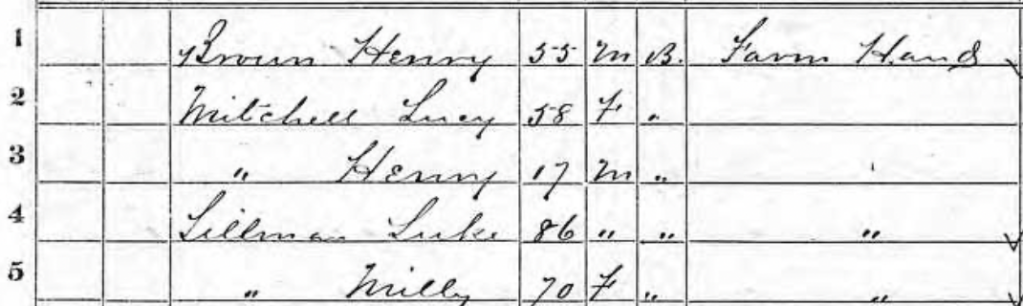

The hands of enslaved people plucked worms from the plants, their fingers snapped buds off the top, and their arms swung hoes to clear the weeds as they slowly moved up and down the rows of the cultivated fields. In addition to the labor of the field hand, the enslaved laborers used a variety of agricultural implements as they moved the stalks and leaves from the fields to the tobacco houses.

Transcription of Advertisement

A Card.

THE undersigned respectfully informs his friends and the public generally that he will continue the MACHINE AND BLACKSMITH BUSINESS, at the old stand, formerly occupied by Mr. FREDERICK GRIEß, in the Town of Upper Marlborough, and will be prepared at all times to make, mend and repair all kinds of AGRICULTURAL IMPLEMENTS, in a substantial and workmanlike manner. TOBACCO PRIZES, THRESHERS, Corn SHELLERS, WHEAT FANS, and all other Implements, made at the shortest notice. Connected with the Machine Shop he has a Blacksmith Shop, and will keep in his employ none but first-rate workmen. He pledges himself to make good work, and to use every effort to please, and respectfully solicits the public patronage.

JOSEPH B. HARRIS. Upper Marlboro’ Jan. 21, 1857—1y

lighting a firework on a hot july night

This unremitting cycle of labor, designed to maximize profit for the enslaver, was met with calculated resistance by the enslaved people forced to endure it. Resistance took many forms, from slowing the pace of work and breaking tools to more overt and dangerous acts of defiance and were often direct assaults on the economic engine of the plantation.

During the hot, humid months of July, while enslaved men, women and children were expected to be vigilant for worms and weeds, while their bodies were bent with the tasks of hoeing, topping, and weeding, the tobacco barns sat empty, waiting for the harvest that was to come in late summer.

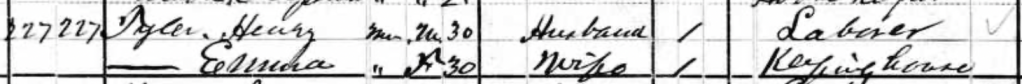

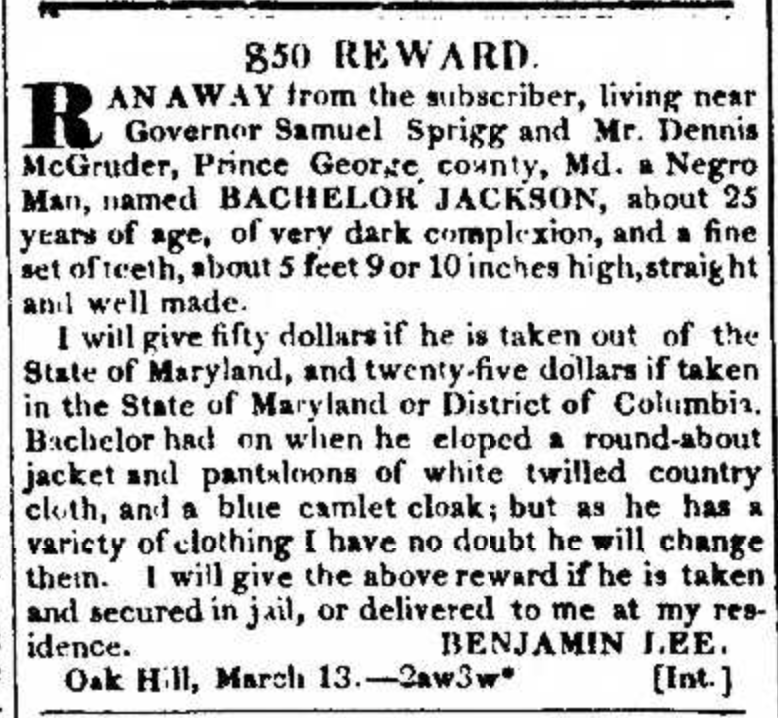

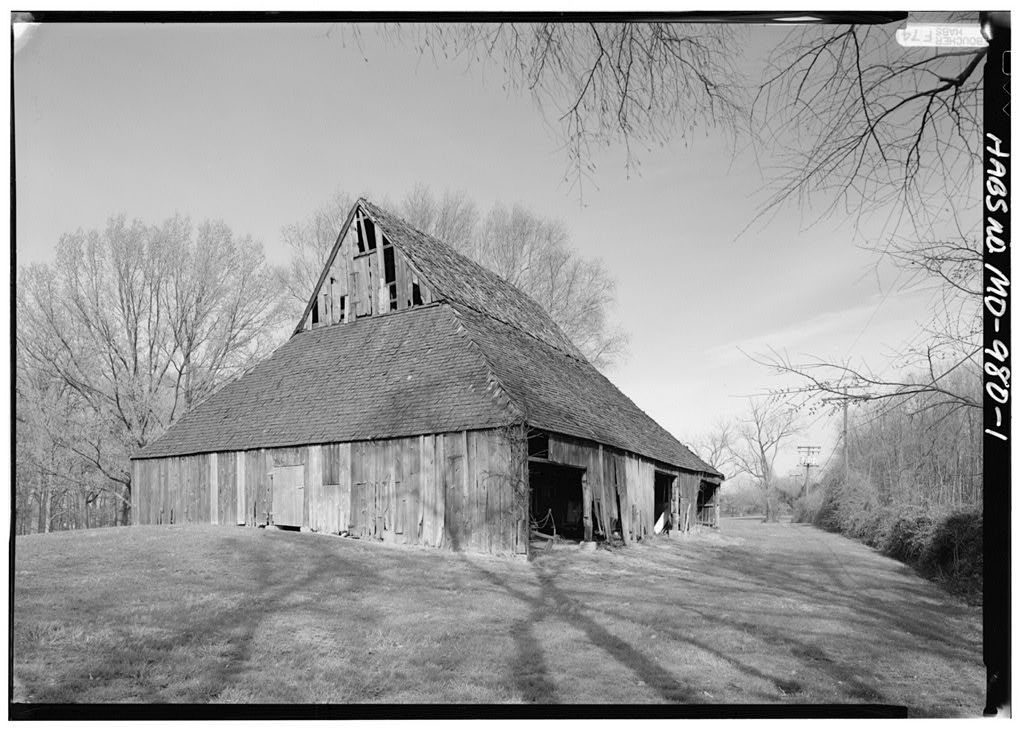

One late night in July, a man left the estate of Dr. Benjamin Lee and walked to a farm of Charles Hill. There, he set fire to the empty tobacco house, which contained a valuable tobacco prize, burning the wooden structure along with nearby shocks of grain.

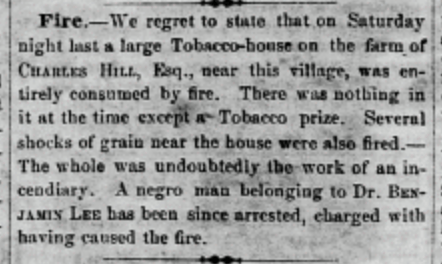

Fire.—We regret to state that on Saturday night last a large Tobacco-house on the farm of CHARLES HILL, Esq., near this village, was entirely consumed by fire. There was nothing in it at the time except a Tobacco prize. Several shocks of grain near the house were also fired.—The whole was undoubtedly the work of an incendiary. A negro man belonging to Dr. BENJAMIN LEE has been since arrested, charged with having caused the fire.

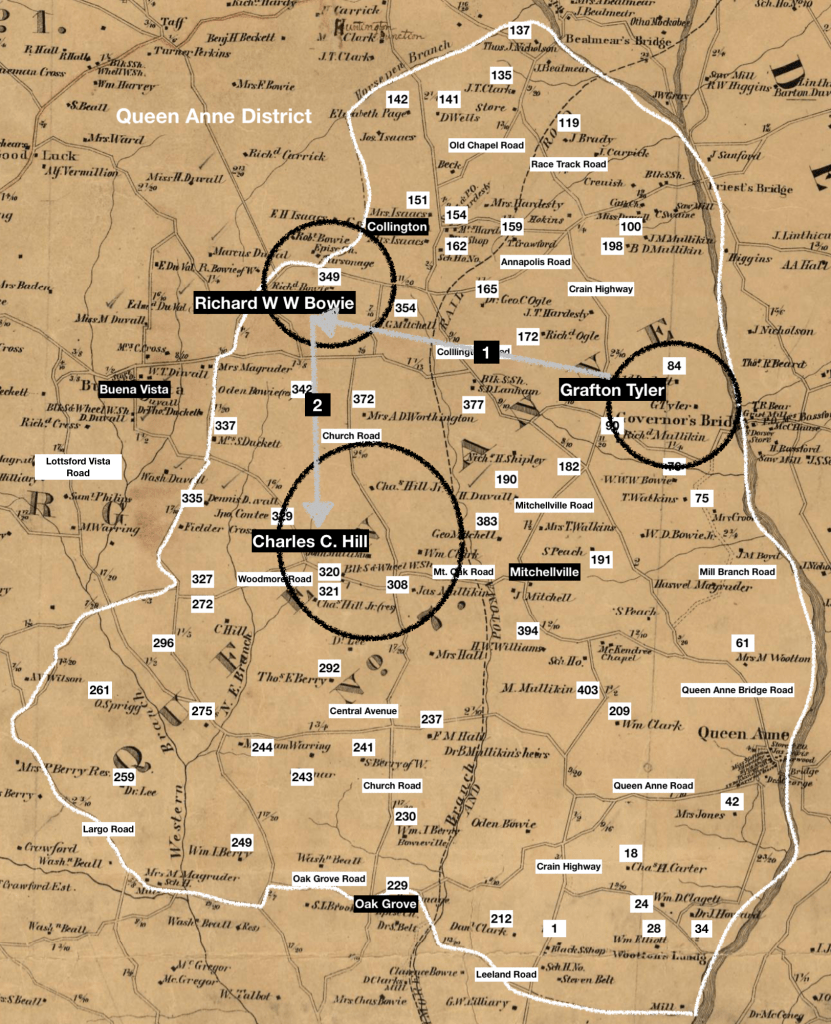

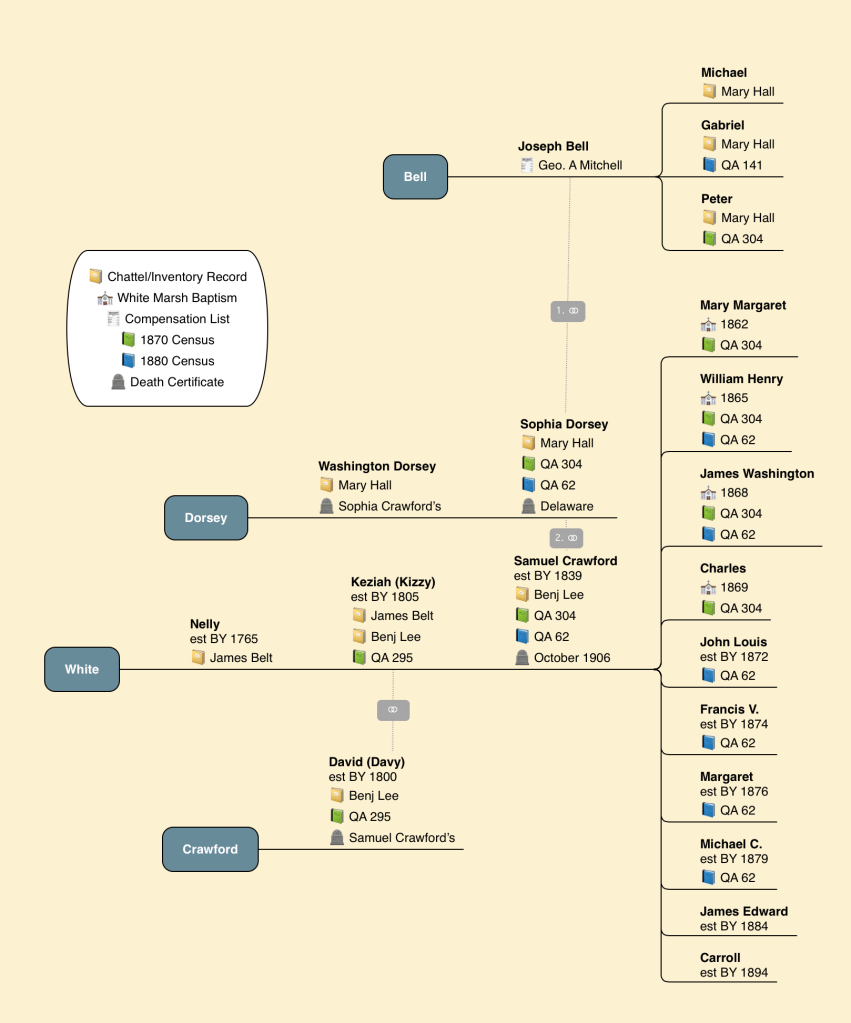

a journey of two miles or four

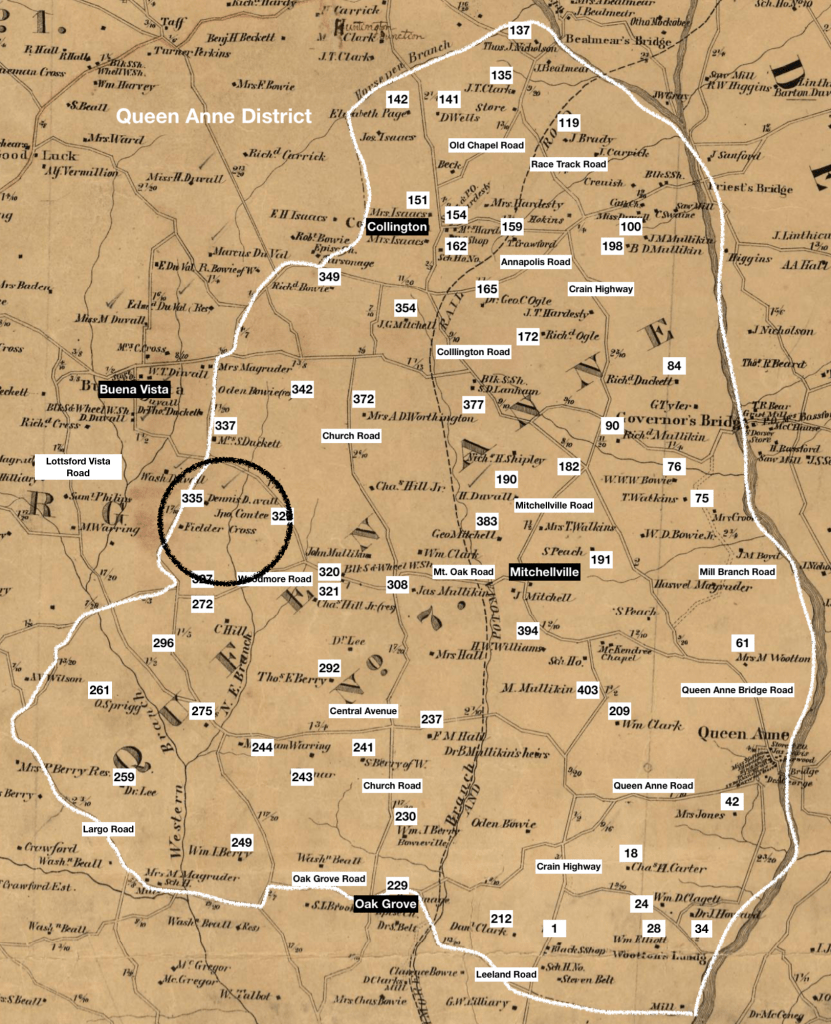

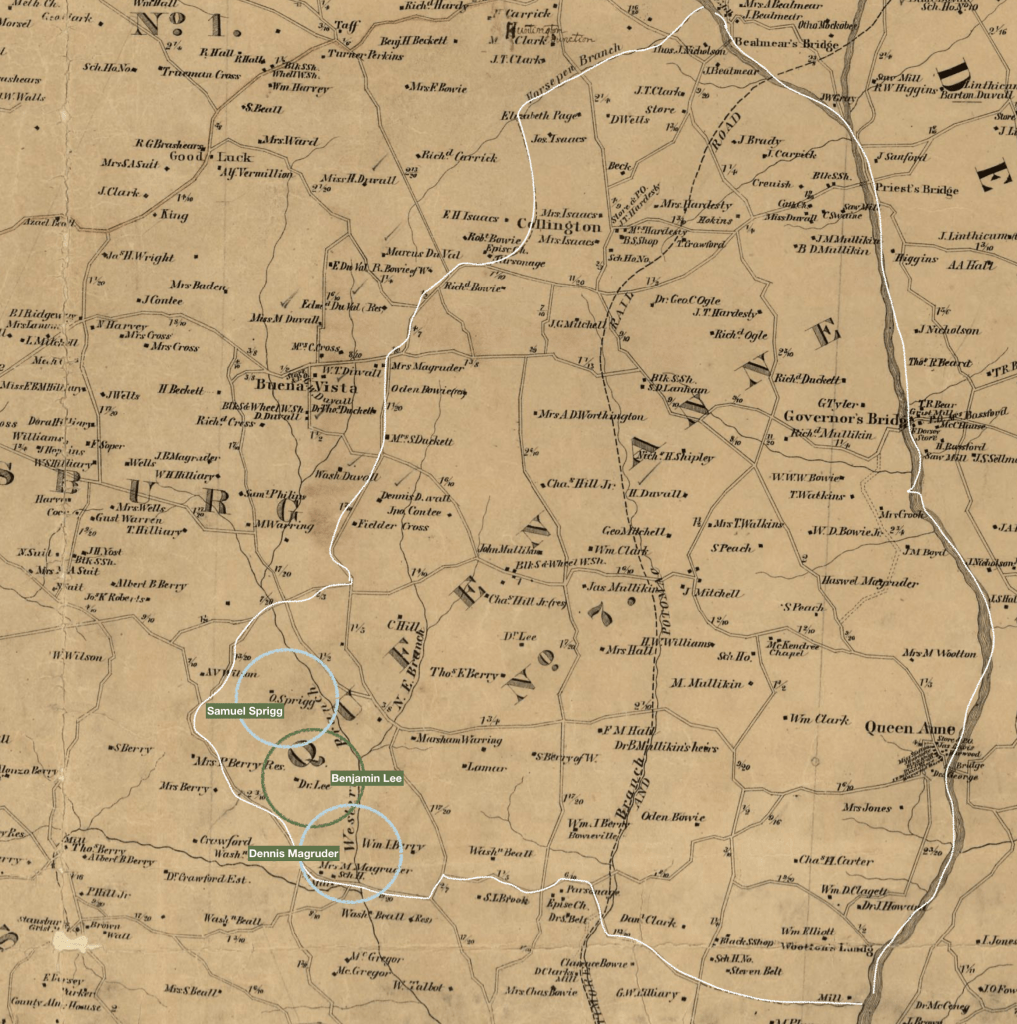

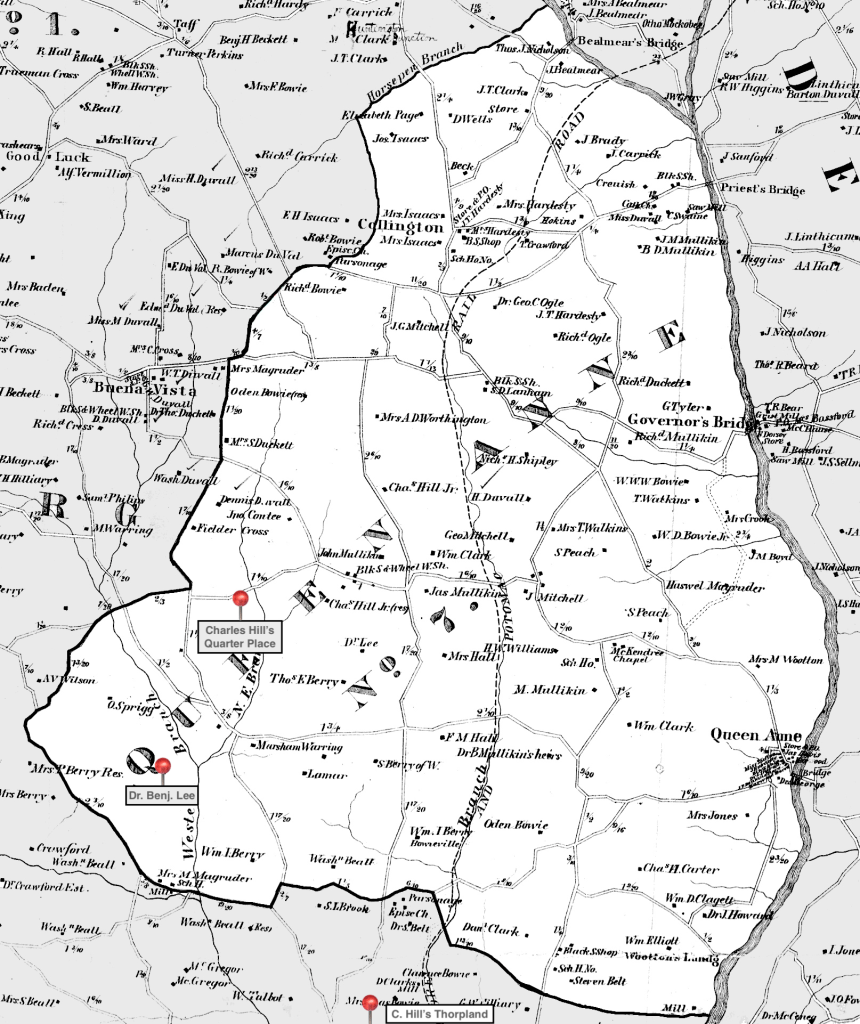

The newspaper’s reference to the fire occurring at a farm “near this village” [Upper Marlboro] initially suggests the target was Charles Hill’s primary residence, Thorpland, located in the Marlboro District. The geography, however, presents a logistical challenge to this assumption. Thorpland was situated four miles from Dr. Benjamin Lee’s property near the Northampton estate, a significant distance for the accused man to travel covertly on foot at night.

A more probable location was a satellite plantation owned by Hill, known as his “Quarter Place.” This farm, managed by an overseer and worked by a contingent of enslaved people, was located only two miles northwest of Dr. Lee’s residence in the Western Branch neighborhood. The shorter, more manageable distance makes this quarter farm the most likely target of the arson, rather than Hill’s more distant home plantation.

Moreover, the report describes the location simply as a “farm.” Had the fire been set at “Thorpland”, the site of Hill’s main residence, the paper likely would have used more specific language to denote the home of a prominent planter, such as “dwelling house,” “estate,” or “the residence of Charles Hill.” The generic term “farm” aligns perfectly with the status of a quarter place—a property that was purely an agricultural operation, distinct from the family seat.

an anxious planter class reassured

The enslaver class responded swiftly through both the legal system and the press. Initially reported in the local Planters’ Advocate, the story was picked up by the Alexandria Gazette, the Baltimore Sun, and the Port Tobacco Times and Advertiser.

His fate now hung precariously between two systems of control. Would he be turned over to the formal legal system to be sold out of state at a public auction, chained in a coffle, and sent to the cotton plantations of the Deep South? Or would his enslaver, Dr. Lee, arrange for his release from the jail, only to “resolve” the situation through the private violence of “plantation justice”—either by a public whipping or a more profitable private sale to a slave dealer from the District?

The fleeting, fiery assertion of his will—a profound risk for liberty—was answered with the permanent, crushing reality of the slave system, a midnight conflagration met with the cold finality of the chain and the coffle under the hot sun.