The 1851 marriage of Alice Carter, daughter of Charles H. Carter and Rosalie E. Calvert, to Oden Bowie, solidified a powerful alliance between two prominent enslaving networks. This union not only consolidated significant landholdings but also intertwined the complex kinship networks of the hundreds of Black people they held in bondage, whose forced labor was the bedrock of their wealth and political power.

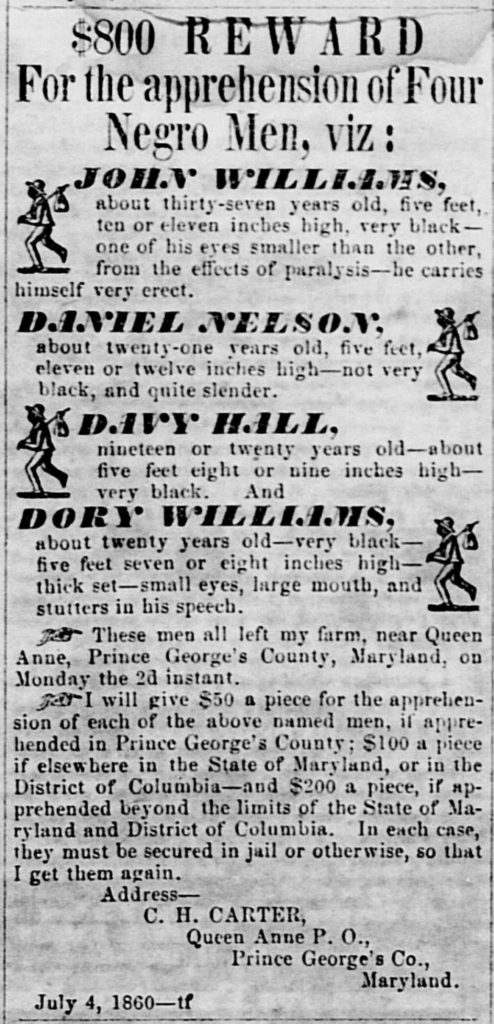

Alice Carter was a scion of the Calverts, descendants of the colonial proprietors of Maryland, and the Carters of Shirley Plantation. Her father, Charles H. Carter operated the “Goodwood” plantation in the Queen Anne’s District, which was inherited from his wife’s family: George and Rosalie Calvert of Riverdale.

Oden Bowie was the heir of William Duckett Bowie and Eliza Mary Oden, with connections to Bowie, Duckett and Oden networks, with their extensive landholdings, including the “Fairview” plantation in the Darnall’s Grove Neighborhood, were equally entrenched in the economic and political fabric of the state. Oden Bowie, a rising figure in Maryland politics, would later become governor.

While Oden and Alice Bowie resided at “Fairview” in the Darnall’s Grove Neighborhood, they purchased a consolidated tract of 471+ acres, composed of land from four older tracts: Smith’s Purchase, part of Dundee, part of Strife, part of Swanson’s Lot in the Wootton’s Landing Neighborhood (CSM 4:177).

This purchases complicates analysis of Oden Bowie’s 1867 compensation list, as the list does not specify which estate the enslaved people labored on (i.e., Fairview or Smith’s Purchase). Another complication in the reconstruction of kinship groups is the lack of transparency around the transfer of ownership during land purchases. Research has shown that land purchases within Queen Anne District may only document the transfer of land with its metes and bounds, but would also contain the transfer of the people who labored in the fields. For example, the Tilghman kinship group conveyed within the Hall network from Francis Magruder Hall to Notley Young’s son in 1826 Hall’s will appears in Charles C. Hill’s 1867 compensation list; Charles C. Hill purchased Elverton Hall from the Young family in the 1850s.

A review of the 1850 and 1860 Slave Schedules show the change in population of the communities enslaved by Oden Bowie. In 1850, prior to his marriage and the acquisition of Smith’s Purchase, the census enumerated 47 people. In 1860, at the dawn of the Civil War, the census enumerated 101 people. The 1867 Compensation List submitted by Bowie lists the names of 103 people.