George Calvert‘s position as a nexus in the Wootton’s Landing Neighborhood was cemented not only through his vast landholdings but also through strategic affinal kinship ties that extended his influence into Virginia. This was a common practice within the planter class to consolidate wealth and forge powerful alliances. This pattern is evident in the 1830 marriage of his daughter, Rosalie Eugenia Calvert, to Charles Henry Carter, a son of the Carter family of Shirley Plantation, one of Virginia’s most powerful slaveholding dynasties. This alliance forged a strategic affinal bridge between a powerful Maryland enslaver network and the Carter dynasty of Virginia.

The scale of the Calvert operation that Carter would come to control is evident in earlier tax assessments. While George Calvert resided at Riverdale in the Bladensburg District in the 19th century, his maintained his Mount Albion plantation in the Wootton’s Landing Neighborhood. In 1828, George Calvert was assessed for 2,777 acres and 93 enslaved people in the Horsepen and Patuxent Hundreds. By 1833, his personal property assessment for the Third District (including what would be Queen Anne District) showed an increase to 100 enslaved people on one list, likely representing the workforce at Mount Albion. Another 1833 list for the same district enumerated 26 enslaved people, possibly those at Oatlands, another Calvert property in the Partnership Neighborhood of Queen Anne District.

Calvert George H_Rosalie Eugenie Carter + husband_AB-11-32-Deed of Trust

Calvert would transfer this property to his daughter in the 1830s. This transfer of property was not merely a familial gift but a calculated transmission of a massive agricultural operation and the enslaved labor force that made it profitable. A Deed of Trust dated November 12, 1836, solidified this alliance and detailed the significant transfer of wealth. The indenture documents how George Calvert conveyed a substantial estate into a trust for his daughter Rosalie’s sole and separate use, managed by himself and Robert E. Lee of Arlington. The assets included a 728 ½-acre tract of land known as “Goodwood,” formerly the core of Mount Albion. Critically, the deed also explicitly transferred the legal title to a community of enslaved people, listing 42 men, women, and children by name and age in an attached schedule. This single transaction established the material basis for Charles H. Carter’s standing within the Prince George’s County enslaver network.

The enslaved population at Goodwood grew under Carter’s control, from the initial 42 individuals in 1836 to 52 by the 1840 census, 58 in 1850, and 76 by 1860. After Rosalie Carter’s death in 1848, the land was conveyed directly to her husband, fully transferring this portion of the Calvert family’s Maryland wealth into the Carter lineage. By 1860, Charles H. Carter’s real estate was valued at $70,000, and his personal estate—a value primarily derived from the external market value of the people he enslaved—was assessed at $55,000. This concentration of wealth and power in the Wootton’s Landing neighborhood was further solidified in the next generation through the marriages of Carter’s daughters, Rosalie Eugenia Carter and Alice Carter, into the Francis Magruder Hall and Oden Bowie families, respectively, perpetuating the cycle of elite kinship consolidation within Prince George’s County.

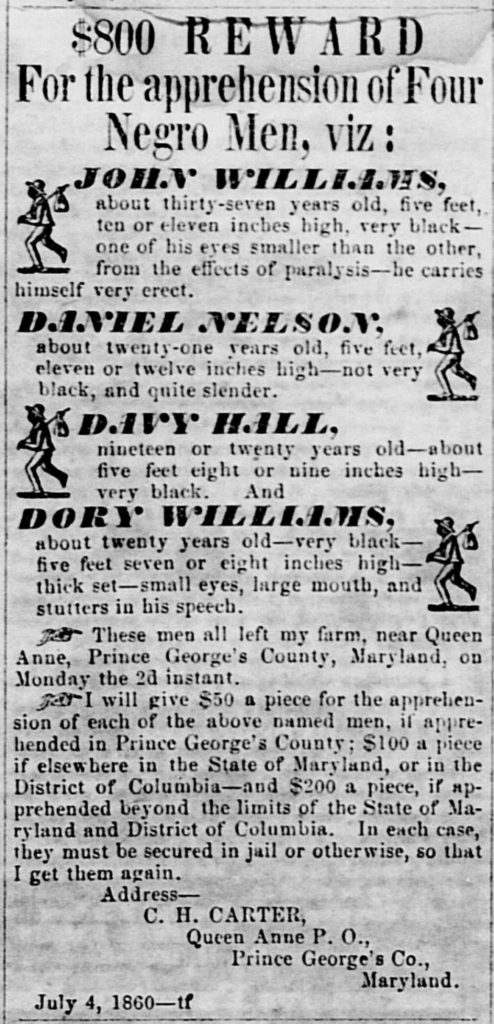

The reconstruction of kinship networks among the people enslaved at Goodwood is fundamentally obstructed by a documentary void. Two key record sets that typically name enslaved individuals from the late antebellum and emancipation era are missing: a probate inventory for Rosalie E. Carter and a post-emancipation compensation claim from Charles H. Carter. While Rosalie E. Carter created a will, it functioned primarily to affirm the conditions of the 1836 Deed of Trust, which stipulated that all real and personal property would be conveyed to her husband for his lifetime, precluding the need for a separate probate inventory. Furthermore, Charles H. Carter, as a nephew of Robert E. Lee, did not file a compensation claim in 1867 for his formerly enslaved human property, likely due to his Confederate ties.Consequently, research must proceed using a limited set of documents. The primary sources are the 1836 Deed of Trust, which provides a schedule of 42 named individuals, including one, Nelly Brown, with a family name, and the anonymous demographic data in the 1840, 1850, and 1860 U.S. Census Slave Schedules. This direct evidence is supplemented by three runaway slave advertisements that identify additional family names: Lloyd Wood, William Brown, John Williams, Dory Williams, Daniel Nelson, and Davy Hall.

Adverstisements