Collateral

A series of financial transactions between Richard W. W. Bowie and others in the 1850s shows Bowie in debt and using Rachel and her children, whom he enslaved, as collateral for his debt.

Richard W. W. Bowie’s father had died in 1839, and his inheritance was controlled by his mother until her death in 1852. Bowie married the same year; joining in matrimony to Elizabeth L Waring, the daughter of Marsham Waring.

In 1852, Richard W. W. Bowie signed an indenture on account of having borrowed $500 from Septimus I Cook. To secure the loan, he sold the legal authority to enslave Rachel (about 30 years old) and her four children: Elizabeth, 10 years old, Mary, 8 years old, John, 6 six years old, and Sophy about three years old to William Holtzman, who secured the loan. (ON 1:157) Holtzman was a merchant living in Vansville District.

In 1854, Richard W. W. Bowie signed another indenture on account of having borrowed $1200 dollars from James T. Perkins. He secured the loan through the conveyance of Rachel (32 years old), Catherine (12), Sophy, (6) and Edward (4). and a “boy” by the name of Isaiah (18) to Richard D Hall, a planter, also residing in Vansville. (ON 2:148)

| Name | Age in 1852 Indenture | Age in 1854 Indenture |

| Rachel | 30 | 32 |

| Catherine/Elizabeth | 10 | 12 |

| Mary | 8 | – |

| John | 6 | – |

| Sophy | 3 | 6 |

| Edward | – | 4 |

Baptismal Records

The same year that Bowie mortgaged the family to Hall, Rachel had a child baptized by the priests of White Marsh. Baptismal records for White Marsh prior to 1853 perished in the fire, and the baptism in 1854 is the first after the fire.

In August 1854, the priests of White Marsh baptized Philomena, the daughter of Eduard Weldon and Rachel Galloway. Rachel was recorded as property of Richard Bowie.

In May 1856, the priests baptized Ann. Elis Welden, the daughter of Eduard Welden and Rachel Galloway. Rachel was again marked as property of R. Bowie.

In July 1859, the priests baptized Anne Maria, daughter of Edward and Rachael Weldon, at Mr. Bowie’s residence.

In April 1863, the priests baptized Mary, daughter of Rachel and Edward Weldon at Rob. Bowie’s residence.

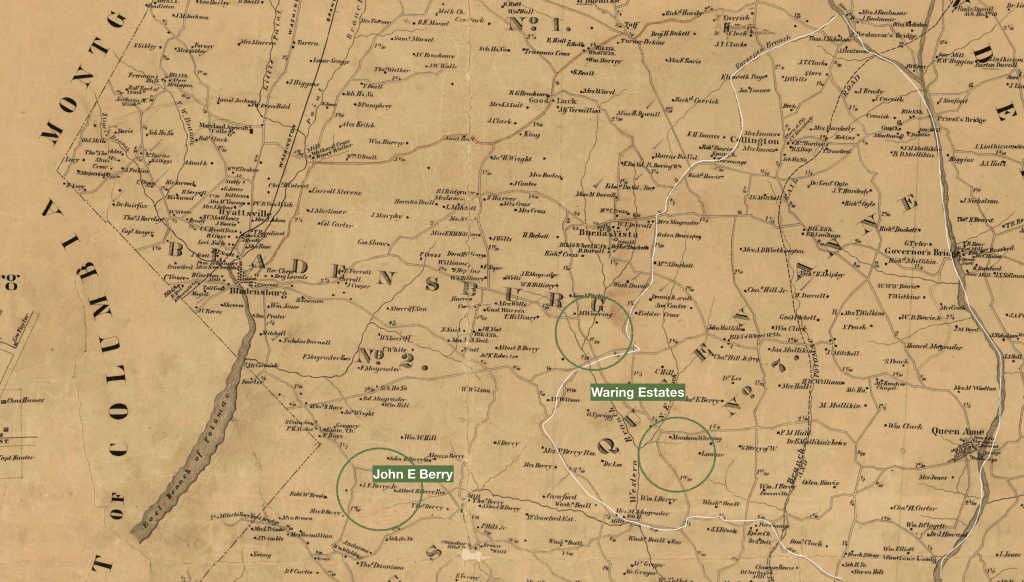

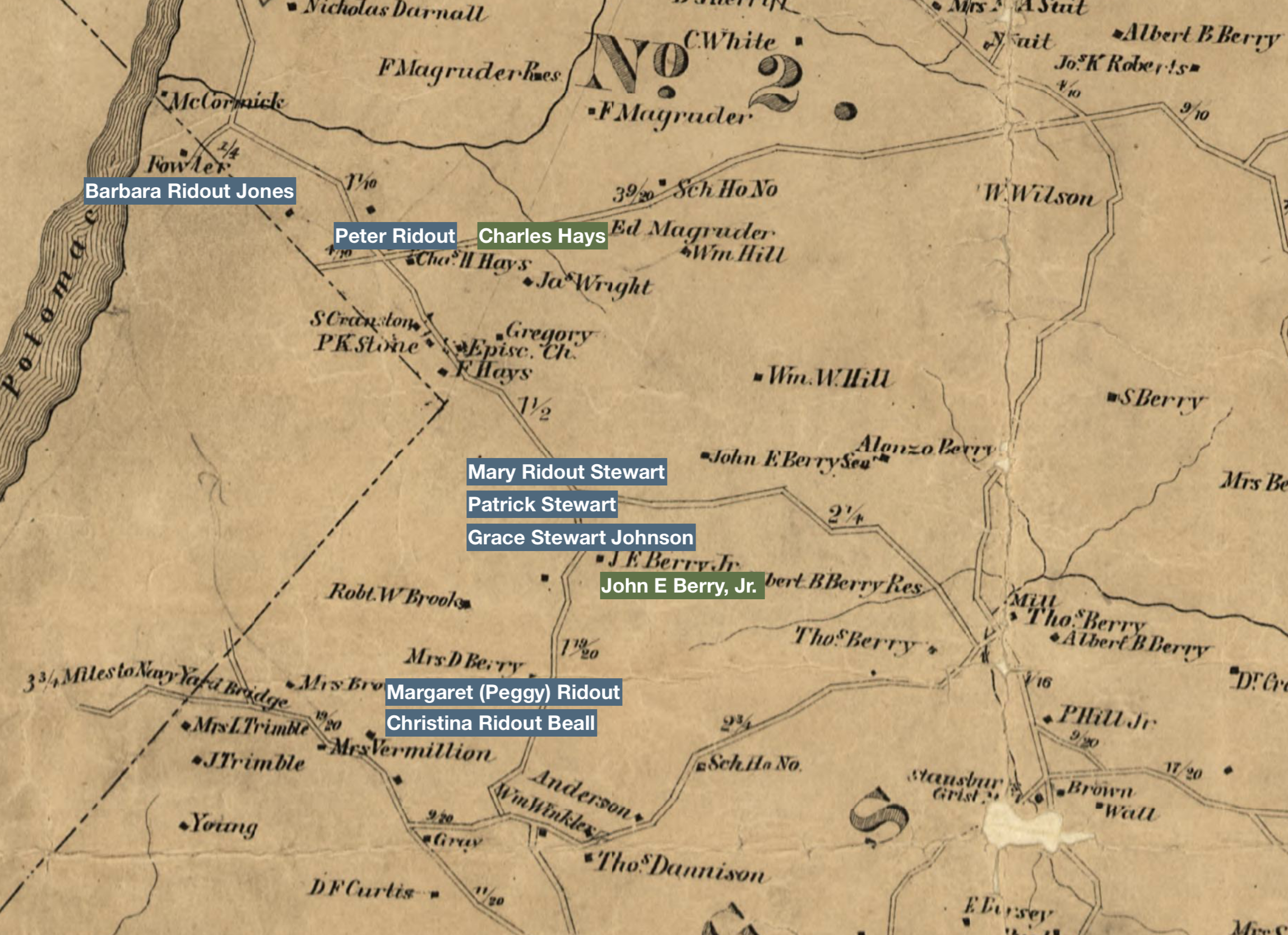

Waring’s Purchases

In March 1857, Richard W. W. Bowie sold the family to Marsham Waring, his father-in-law for $2000, most likely allowing him to maintain possession of the family at his estate for the use of Waring’s daughter, Elizabeth L. Bowie. (CSM 1:538) This transaction was not secure a debt, rather was a bill of sale, in which he sold the legal authority to enslave Rachel, age 35, Catherine, age 13, Sophia, age 7, Edward, age 5, Philla, age 3, and Elizabeth age 1. The Bill of Sale does not mention her husband Edward Welden; it is unclear who enslaved him, as priests did not consistently record the father’s slaveholder.

| Name | Age in 1852 Indenture | Age in 1854 Indenture | Age in 1857 Bill of Sale |

| Rachel | 30 | 32 | 35 |

| Catherine/Elizabeth | 10 | 12 | 13 |

| Mary | 8 | – | |

| John | 6 | – | |

| Sophy | 3 | 6 | 7 |

| Edward | – | 4 | 5 |

| Philla (Philomena) | 3 | ||

| Ann Elizabeth | 1 |

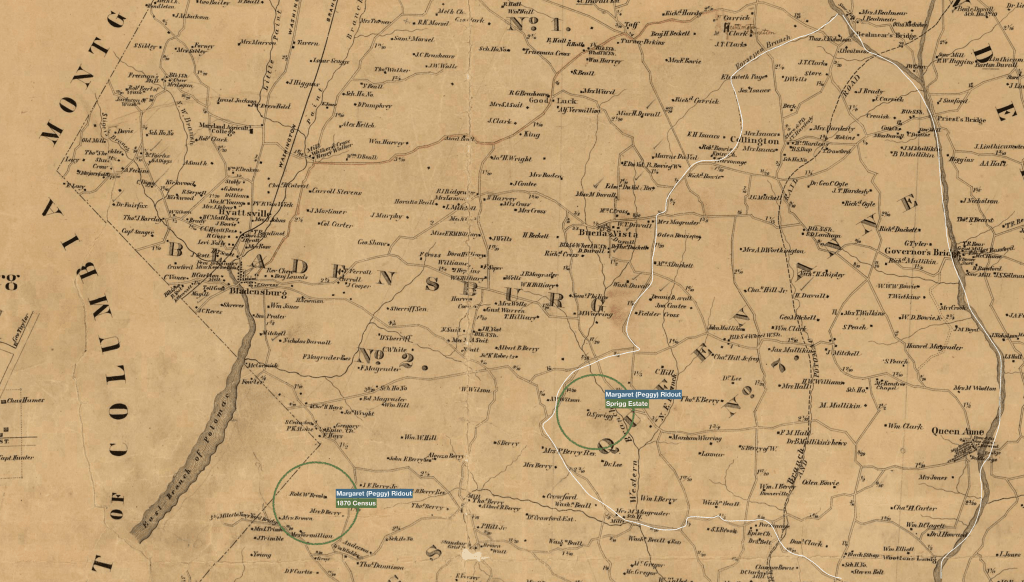

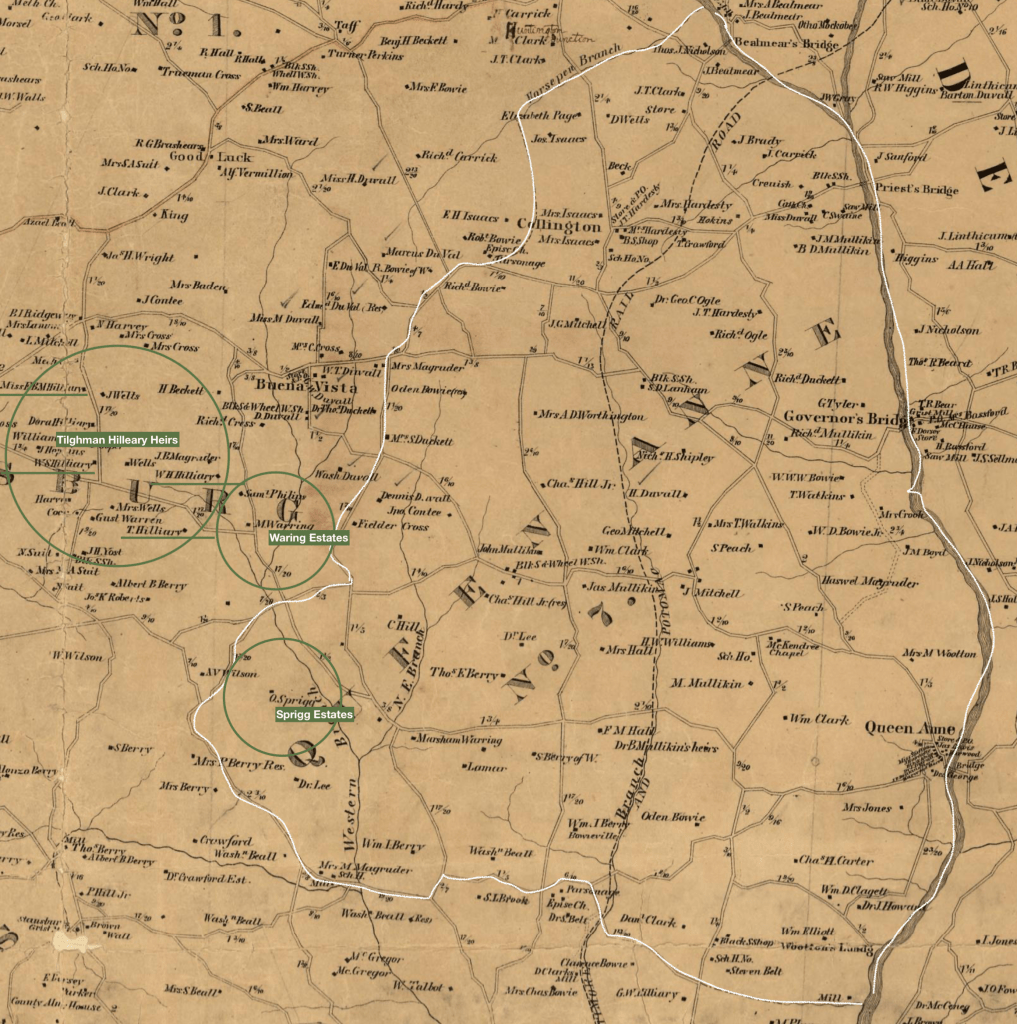

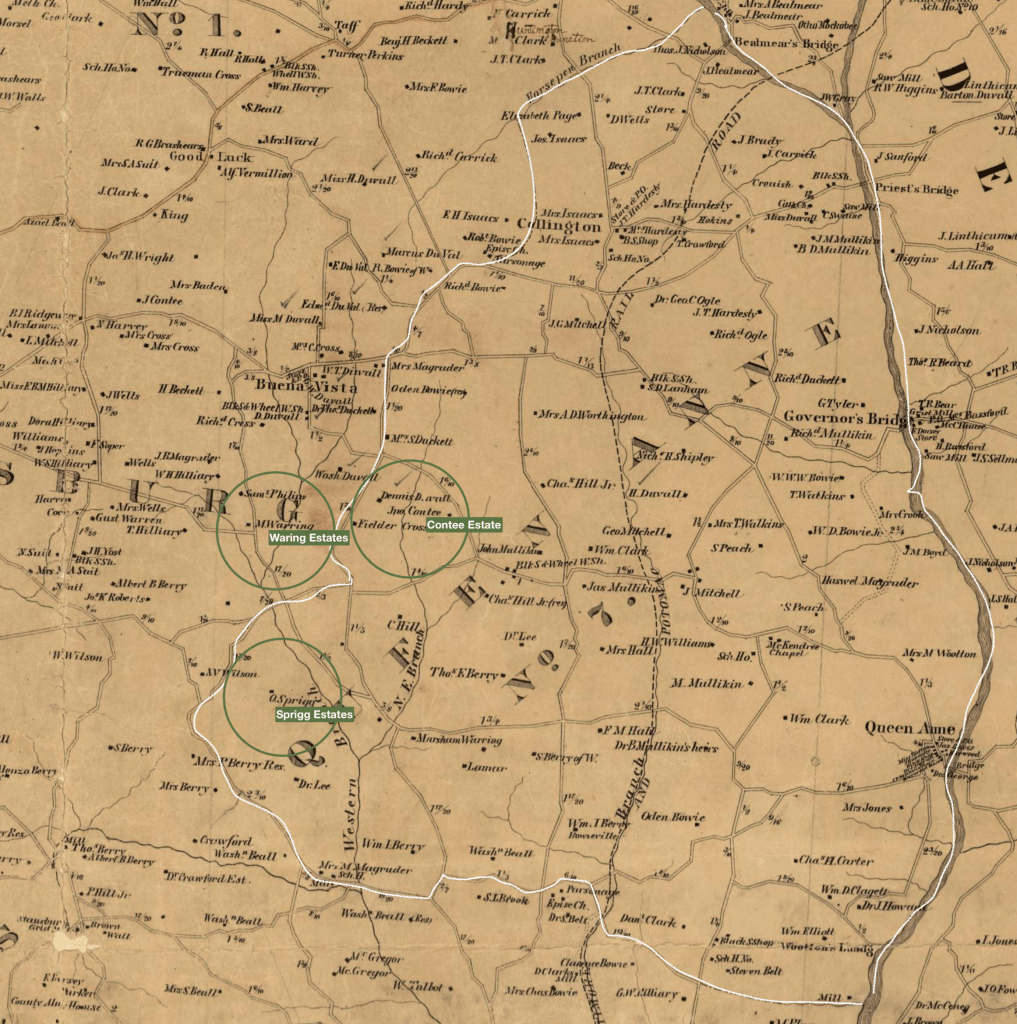

In February 1859, Richard W. W. Bowie was paid $3000 by his brother Walter W. W. Bowie to relinquish claim to land described in the 1839 will of his father, Walter Bowie, particularly “Locust Grove”. (CSM 3:117)

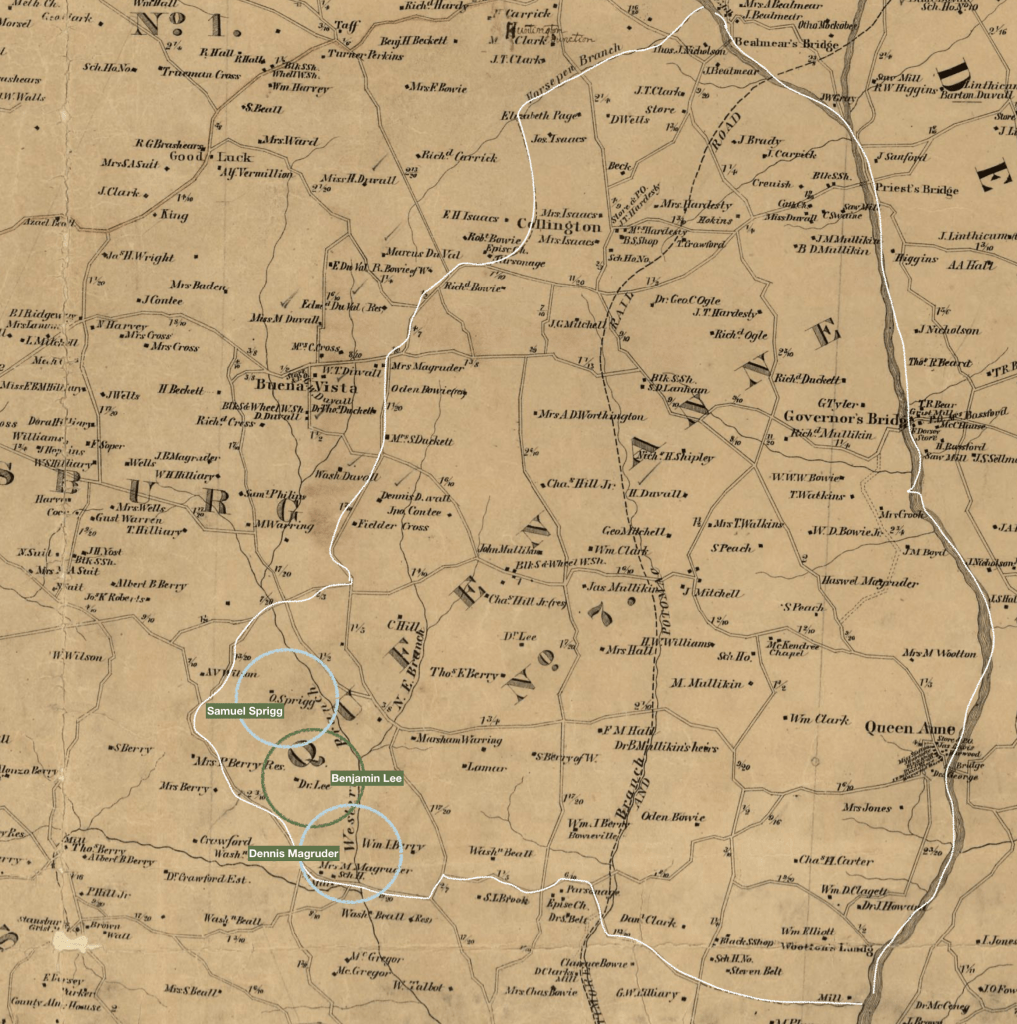

Then, in the same month, Marsham Waring purchased the lot and parcel of land “known as part of Darnall’s Grove” and called “Locust Grove”, for $15,190 from Walter W. W. Bowie. (CSM 3:538) The Daily Exchange, a paper out of Baltimore, reported the sale.

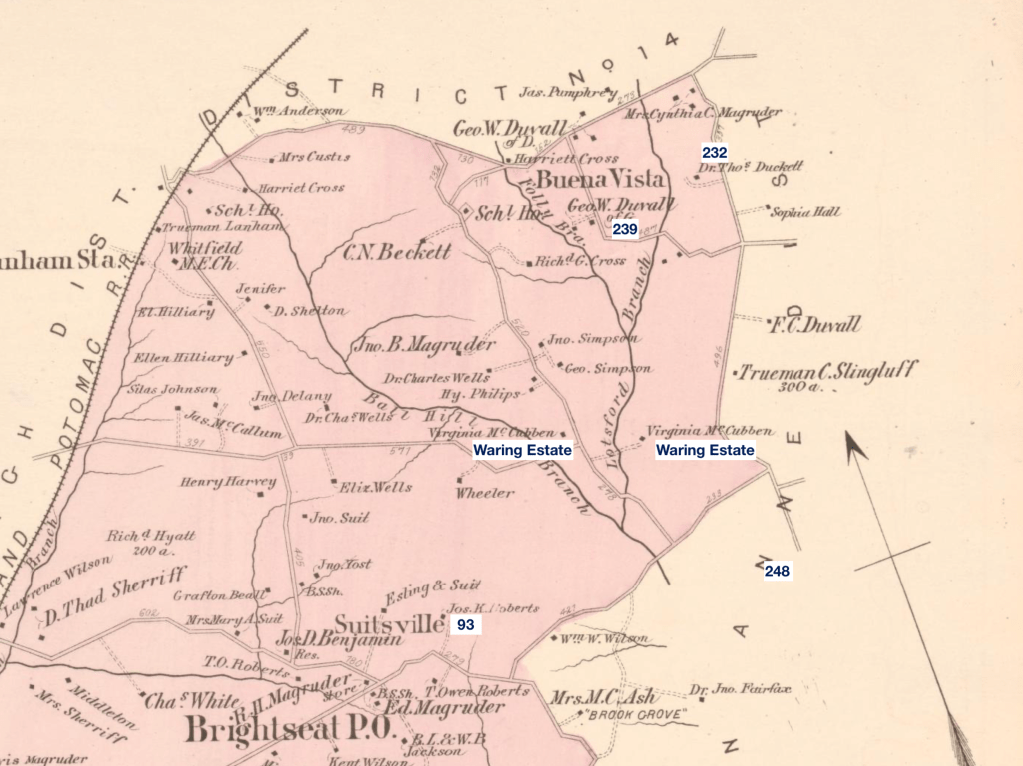

In Waring’s 1860 will, he directed that the farm “Locust Grove” go to his son James Waring, “for the use and benefit of my beloved daughter Elizaebth L Bowie [Richard W. W. Bowie’s wife], the plantation which I purchased of Walter W. W. Bowie” In his inventory, the people enslaved by Waring were organized by estate and 9 people were named as laboring on Locust Grove: Anna, 22, George, 4, Mary 15, Sam, 35, and Rachel 28, Catherine, 16, Edward, 8, Eliza, 8, and Maria, infant. Rachel and her children made up the bulk of the people named on the estate.

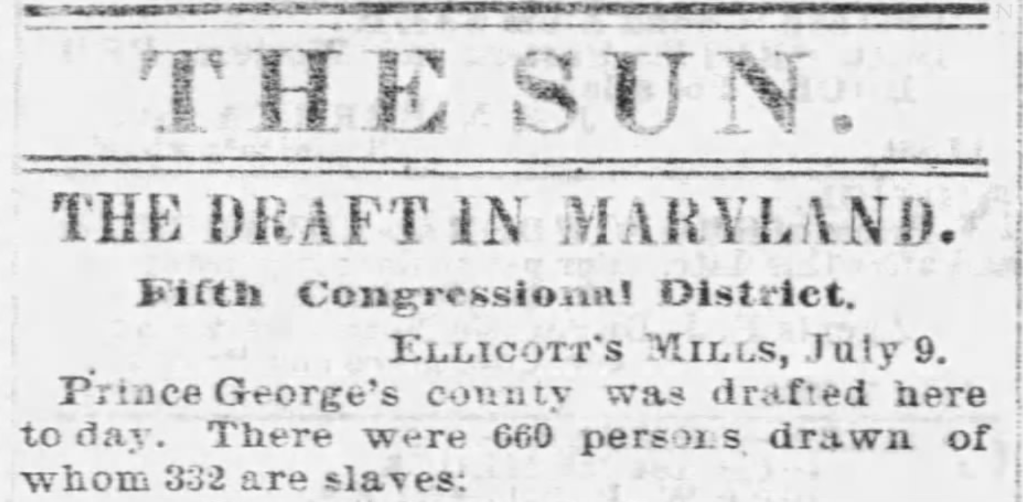

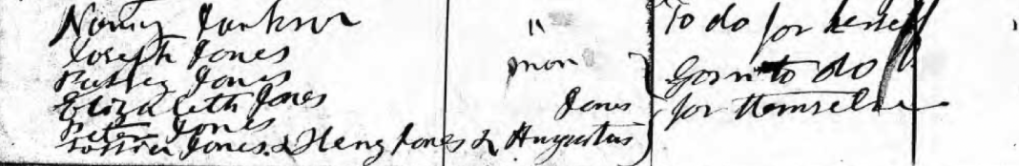

After Waring’s Death

In May 1862, Catherine Weldon, the daughter of Edward and Rachel, fled to the District with other people from the Waring estates. She is named in the affidavit that James Waring took out. The month prior, in April 1862, the District had abolished slavery and those enslaved in the neighboring jurisdictions fled to the freedom it promised along with the Federal Troops who offered a modicum of protection against slave patrols and slave catchers. Many named in affidavit and their extended family are found in the records of the freedmen’s camps (see Jones Family Group and Stewart Family Group posts). Records connected to Catherine have yet to be located. Though in February 1867, Rachel Weldon is recorded as receiving a nominal amount from a Freedmen Bureau’s agent in the District.

In April 1867, the priests of White Marsh baptized Edward, the son of William Franklin and Catherine, his wife. Martha Sprigg, a woman formerly enslaved by the Warings, sponsored the baptism. Martha’s son, Daniel, was baptized the same day. Edward was likely named for her brother and father.

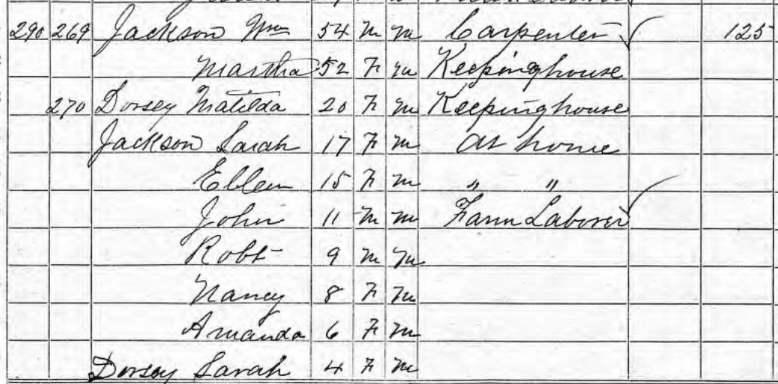

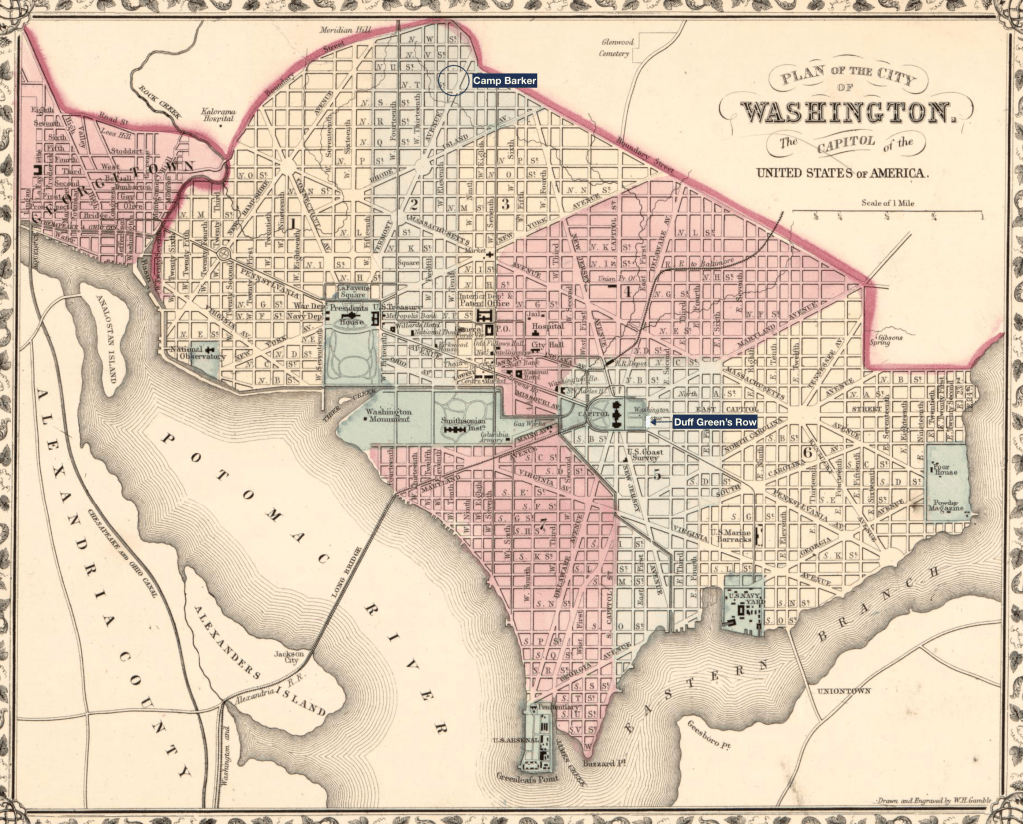

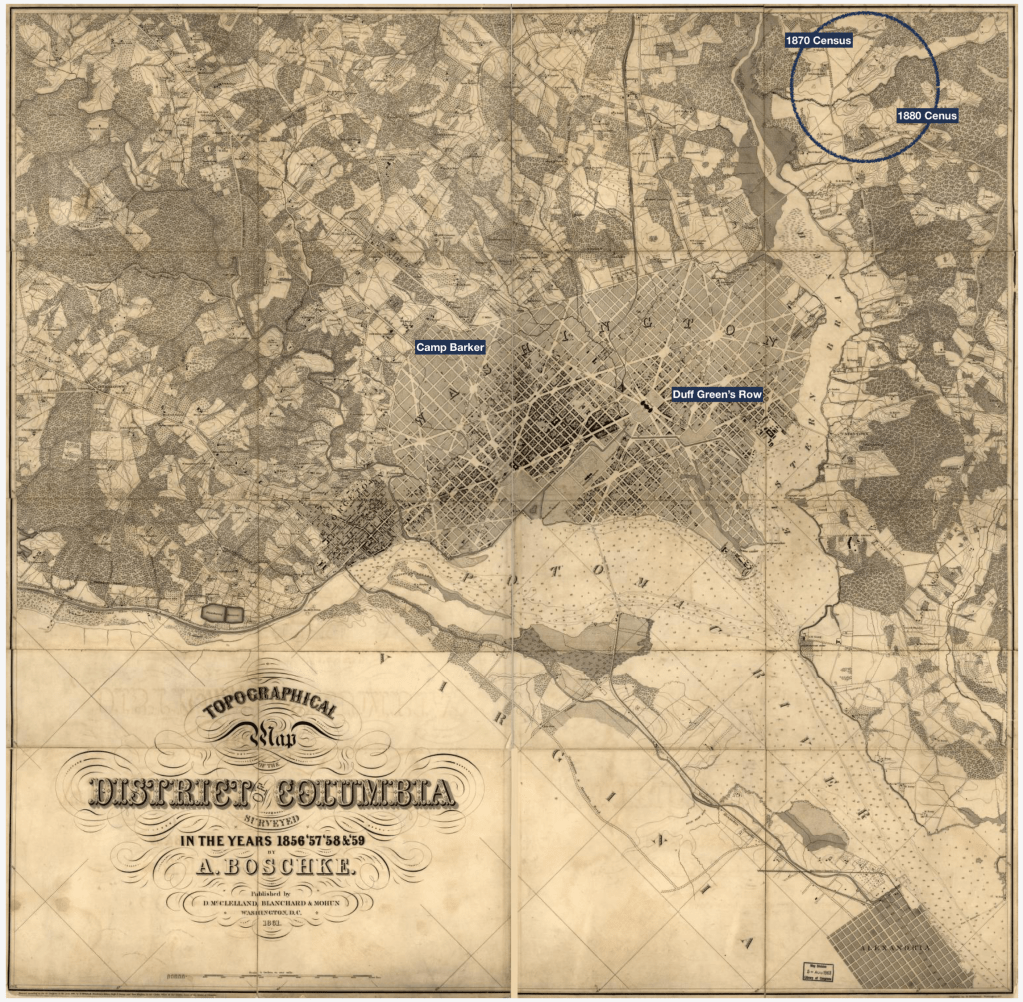

In 1870, Edward and Rachel Weldon were living in the District of Columbia, in Ward 6 with their son Edward. Both Edward’s are working as laborers. City Directories place them near Lincoln Park. In 1880. the census records Edward and Rachel at 328 Ninth Street SE with their grandchildren. Rachel died in October 1884 and was buried at Mt. Olivet Cemetery. Edward died in 1889 and is also buried at Mt. Olivet.

In 1870, Catherine and William were living in Queen Anne District in the vicinity of Collington with three children and in 1880 they were living in the vicinity of Bowie. FrankWeldon, age 48, is living in their household. He is perhaps an older brother or uncle of Catherine.

Rachel’s Family Group

Rachel partnered with Edward Weldon. The extended Weldon family had multiple baptisms recorded in the surviving White Marsh Baptismal records and many were connected with the Mary Hall estate. In the 1861 Inventory of Mary Hall’s estate, two elderly people are named: Frank and Becky. Based on their age in the inventory, they were born around 1790. In 1822, a priest of White Marsh baptized Catherine, daughter of Francis “Welden” and Becca Sprig. The name Catherine would also be used by Edward and Rachel suggesting a relationship between the Weldons enslaved by the Bowies (Edward Welden and his children) and the Weldons enslaved by the Hall family (Francis Weldon and his children)

Two direct sources provide two possible names for Rachel’s family: Galloway and Mahoney. The Baptismal Records lists Rachel as Rachel Galloway in 1854 and 1856 baptisms of her children. This source most likely had either Rachel or her enslaver providing the name for her family, and therefore directly knowledgeable about her family connections. The second source is a death record for Catherine Franklin, who died in Dec 1911, almost thirty years after Rachel. Her son listed his grandparents, and Catherine’s parents as Edward Weldon and her mother as Rachel Mahoney.

Mahoney is connected with a family with direct ties to White Marsh, as Charles Mahoney had sued John Ashton, manager of White Marsh for his freedom in the 1790s. William G. Thomas wrote a fascinating book about this suit and others, called A Question of Freedom: The Families Who Challenged Slavery from the Nation’s Founding to the Civil War. The Hall Family was descended from Benjamin Hall who is said to have taken possession of Ann Joice after she was illegally denied freedom at the end of her indenture. The Mahoney family was descended from Ann, and three Mahoney’s were named in the will of Francis Magruder Hall in 1826. Francis Weldon and Becca Sprigg were named by Hall as well in his will. The death record that connects Rachel to this family group is from a less reliable informant than the informant of the baptism records due to the nature of memory. Based on depositions given by the members of the Mahoney family during their freedom suits, their family passed on an oral tradition of how they were related to Ann Joice, which may have continued after the end of the freedom suits.

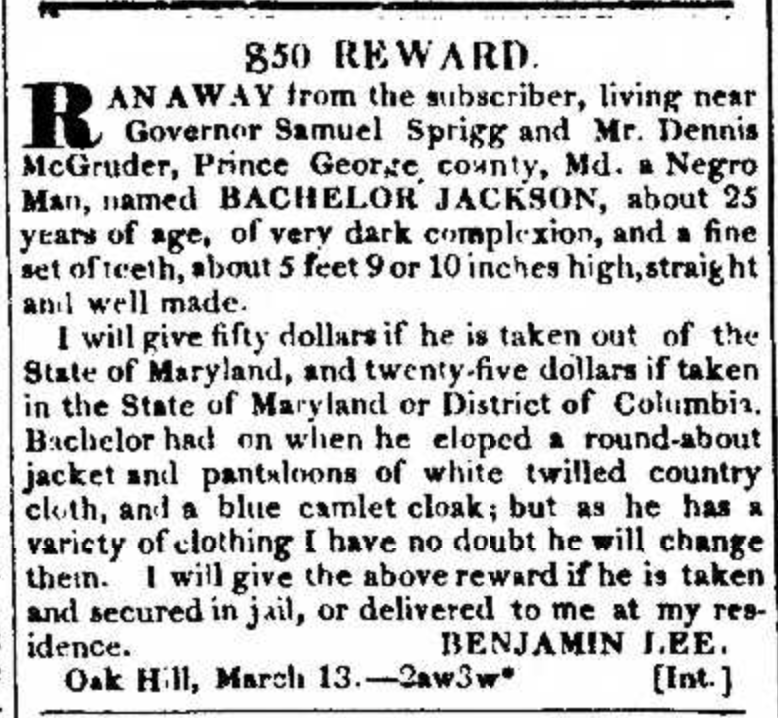

The family name Galloway has fewer baptisms than Mahoney or Weldon. In 1832, the priests baptized Charles, the son of Patrick and Henrietta Galloway who was enslaved by Robert Bowie. The sponsor was Kitty from White Marsh. Seven years earlier, a Charles Galloway escaped the captivity of Mary Weems living in Prince George’s County. He was described as a mulatto man about 21 years of age with relations in the city of Washington. Mary Weems, who advertised for Galloway’s return, may be Mary Margaret Hall who married James William Loch Weems and the grandmother of Walter W. W. Bowie and Richard W. W. Bowie. Mary Margaret Hall and Francis Magruder Hall were siblings, and therefore likely to partner their enslaved young adults.

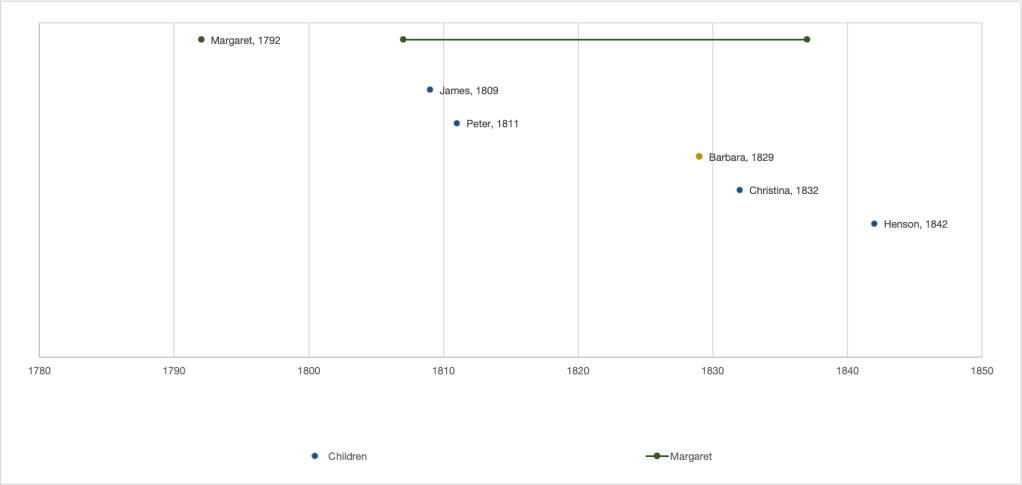

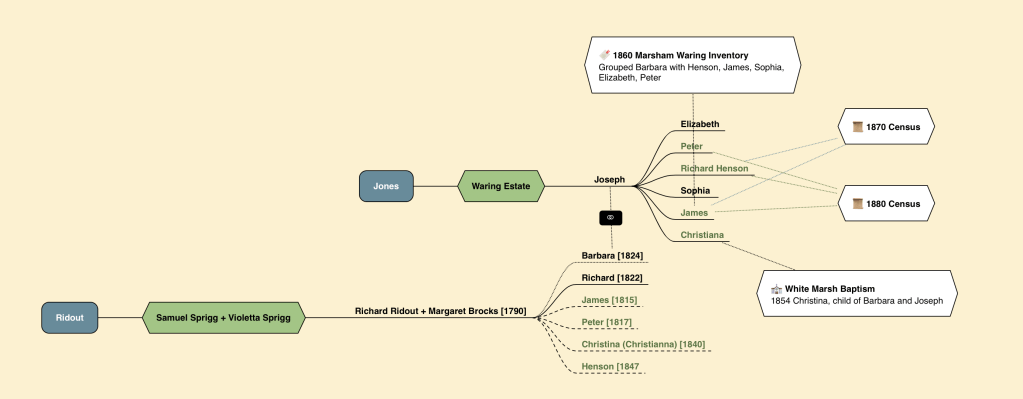

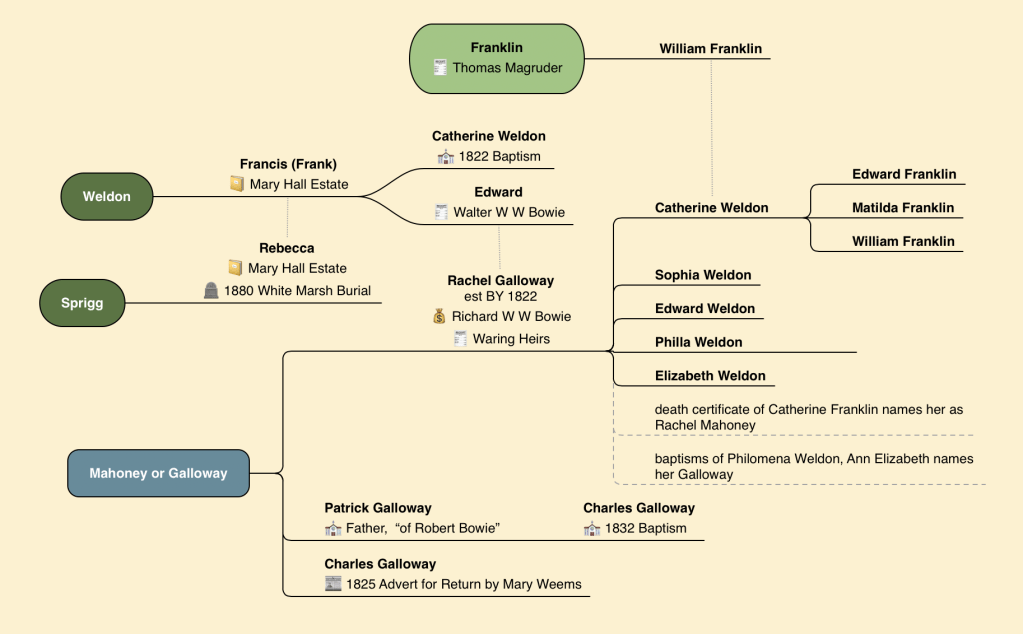

The two diagrams below show the relationships visually. The first shows the connections between the slaveholders. The second diagram shows the family connections of Edward and Rachel Weldon as constructed from direct and indirect evidence, and the estates they were were associated with.

Mary Weems died in 1849, and the 1850 inventory of her estate shows a family group that may be Rachel and children born prior to the surviving baptismal records of White Marsh. (PC 1:384) Rachel, age 30, would have an estimated birth year of 1820, similar to Rachel Galloway’s age given in the multiple Bowie transactions. Additionally, she had a daughter, Catherine, age 5, would would have an estimated birth year of 1845. The 1857 Bill of Sale between Bowie and Waring had an age of 13 for Catherine which would result in an 1844 estimated birth year. Additionally, the oldest daughter, Henny, may have been named for Henrietta Galloway, the mother named in the 1832 baptism, an inferred relative of Rachel.