The 1836 schedule for the deed of trust transferring the Goodwood plantation to Rosalie E. Carter from the Calverts lists Eleanor “Nelly” Brown at age 35, establishing her calculated birth year as 1801. Her youth unfolded during the Early Republic Generation (1790-1815), a period of significant economic volatility shaped by the Napoleonic Wars. Trade embargoes depressed agricultural prices, creating economic distress for yeoman farmers who could not afford to store their produce. In contrast, the economic structure enabled elite planters like the Calverts to leverage their substantial capital and storage capacity. They acquired tobacco and other commodities at low rates from distressed sellers and profited when markets rebounded, a cycle that consolidated their wealth and reinforced the system of chattel slavery that held Nelly Brown in bondage.

To read more about the wealth inequalities of the Early Republic and specifically in relation to the Calverts, see Steven Sarson’s article: “It cannot be expected that I can defend every man’s turnip patch”: Embargoes, the War of 1812, and Inequality and Poverty in the Chesapeake Region

By the time of the deed of trust, written during the Jacksonian Generation Eleanor Brown was nearing the end of her “prime years” as a laborer and breeder for the Calverts. Despite the commodification of her body by the Calverts and the Carters, Eleanor Brown maintained a soul value in her roles as mother and aunt on the large estate of Goodwood.

Daina Ramey Berry’s book Their The Price for Their Pound of Flesh: The Value of the Enslaved, from Womb to Grave, in the Building of a Nation offers a critical examination of the commodification of enslaved people. Berry meticulously details how enslavers and the slave market assigned an “external appraisal value” or “external market value” to enslaved individuals based on factors such as age, gender, health, and perceived productivity, and contrasts this with “internal spirit value” or “soul value” of enslaved people. While enslavers reduced individuals to mere commodities, Berry highlights the ways in which enslaved people themselves cultivated an intrinsic sense of self-worth and humanity that defied their commodification.

While it is unclear why the Calvert-Carter network designated her family name, she was grouped in the schedule of enslaved people in what appears to be a mother-child lineal grouping, signifying her kinship role to the larger enslaved community. As an adult woman, she was followed by the names of five children — usually this was an organization technique used by clerks to infer kinship.

| Nelly Brown | age 35 |

| Emeline | age 14 |

| William | age 11 |

| Dennis | age 8 |

| Maria | age 4 |

| John | an infant |

The mother-child lineal grouping raises questions that are not answered in the records. For example, the gap in ages between Maria and Dennis is four years, which is longer than the three year gaps between Emeline-William, William-Dennis. This longer gap suggests three possibilities grounded in the exploitative structure of chattel slavery. The first possibility is an unrecorded infant death. Nelly may have borne a child who did not survive long enough to be recorded, a frequent outcome resulting from the inadequate nutrition, disease, and physical demands of enslavement. Second, the interval may reflect a period of poor maternal health, where a difficult prior birth or illness precluded a subsequent pregnancy. The third possibility is forced separation, a method enslavers used to exert control. The Calverts could have separated Nelly from her partner by selling him, hiring him out to another location, or moving Nelly herself. The archival record does not reveal which of these realities Nelly experienced, and its silence underscores the system’s disregard for the integrity of enslaved families.

liberation of William Brown

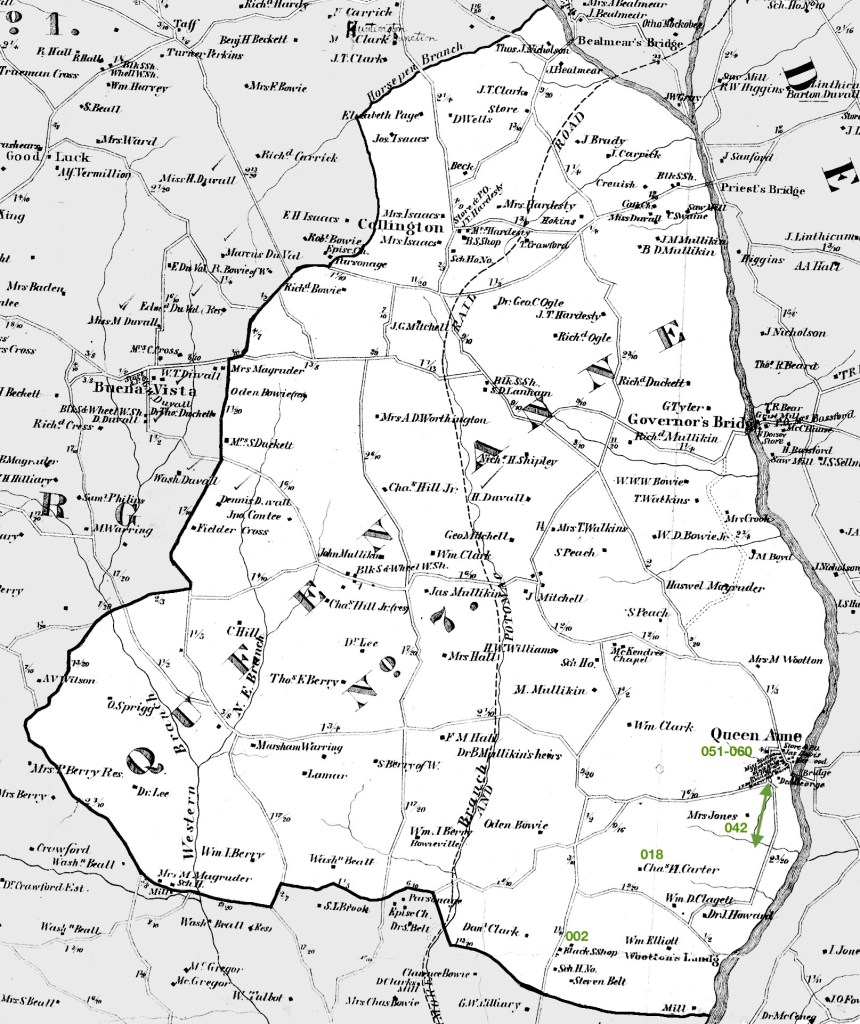

Seventeen years later, in an advertisement dated April 20, 1853, Charles H. Carter announced that William Brown, an enslaved man, had self-liberated from Goodwood. Carter described William as “about thirty years of age”. This detail provides a calculated birth year of approximately 1823, which is consistent with the inferred son of Nelly Brown, listed in the 1836 schedule, as William, age 11.

Given that enslavers often provided estimated ages in runaway advertisements, the two-year age difference is minor and the shared family name “Brown” from the 1836 schedule strongly suggests that the man who self-liberated in 1853 was part of this kinship network at Goodwood.

Tracing William Brown beyond the advertisement is difficult as both his given and family name are common, obscuring if he found a temporary freedom or a permanent liberation from slavery.

| advertisement |

| $100 REWARD WILL be paid for the apprehension of my negro man, William Brown, who left home on the 14th instant. He is a mulatto, about thirty years of age, five feet eight or nine inches high, rather stout make: turns his toes out in walking and limps in consequence of a sprained ankle. He has a wife at Mr. Azell Beall’s, near Buena Vista, and may be there, or in the neighborhood. I will give fifty dollars for his apprehension, if taken in the District of Columbia, Prince George’s or Anne Arundel Counties—seventy-five dollars, if taken in Baltimore—and one hundred dollars, if taken elsewhere—in either case, he must be secured, so that I get possession of him again. C. H. CARTER,”Good Wood,”Near Queen Anne,P. G. Co. April 20, 1853—2w [Planters’ Advocate and Southern Maryland Advertiser; MSA] |

post-emancipation life of Emeline

While the fate of William Brown is obscured, Eleanor (Nelly) Brown’s daughter has been tentatively identified in the 1870 Census, living near Queen Anne Towne.

The household of Benjamin “Benny” West and Emily Brown, located in close proximity to Charles H. Carter’s former Goodwood estate was enumerated at dwelling number 48. The presence of this family presents a compelling, though not conclusive, hypothesis for a direct link to the community enslaved at Goodwood three decades prior.

| 1870 Census |

| 🟢👑 DN 48 | 📮: Mitchellville | 📍 Queen Anne Towne Benny West, age 50 (calc. birth year 1820) Emily Brown, age 45 (calc. birth year 1825) Morris Brown, age 19 (calc. birth year 1851) Maria Brown, age 14 (calc. birth year 1856) Ella Brown, age 12 (calc. birth year 1858) James Brown, age 5 (calc. birth year 1865) Eleanor Brown, age 12 (calc. birth year 1858) Sophia Brown, age 3 (calc. birth year 1867) Louisa Brown, age [1] (calc. birth year 1869) |

The primary evidence centers on Emily Brown, listed as 45 years old in 1870, and her potential connection to Emeline, a 14-year-old girl enumerated in the 1836 Deed of Trust schedule for Goodwood. While the calculated birth years (~1825 for Emily vs. ~1822 for Emeline) show a minor three-year discrepancy, such inconsistencies are common in records where ages were often estimated. The link is strengthened through given name analysis. Given this context, “Emeline” and “Emily” are recognized as plausible variations for the same individual, much like other variants such as “Amelia” or “Emilia.”

The most powerful, albeit circumstantial, evidence lies in the naming patterns that suggest a deliberate effort to maintain kinship identity. The 1836 schedule lists Emeline as part of a cohort headed by Nelly Brown, age 35. The discovery of a daughter named Eleanor in Emily Brown’s 1870 household is therefore highly significant. For communities emerging from chattel slavery—an institution that systematically severed familial bonds—the act of naming a child after a parent or grandparent was a potent method of reinforcing lineage. As “Nelly” is a common diminutive for “Eleanor,” it is a strong possibility that Emily Brown named her daughter in honor of her own mother, Nelly Brown. While no single piece of this evidence is definitive, the combination of proximate age, plausible name variation, and the commemorative naming choice makes a strong circumstantial case for the continuity of the Brown family line from enslavement into freedom.