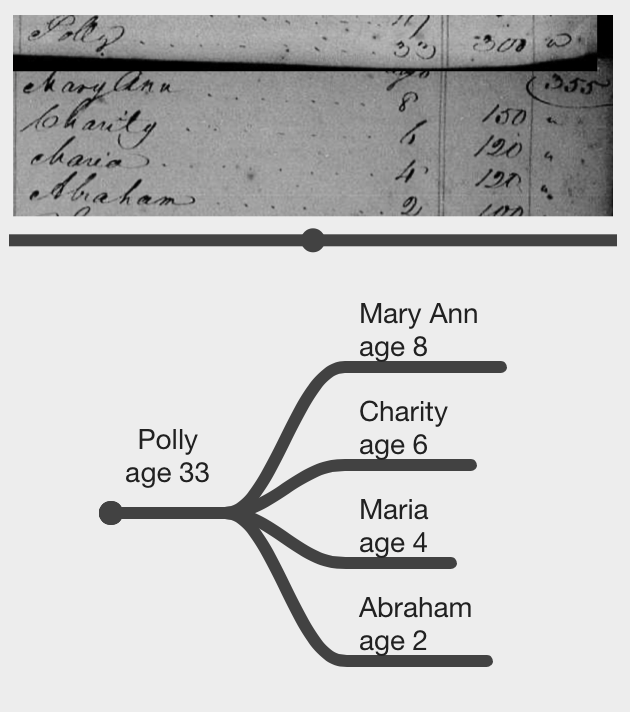

After the Civil War ended, Dinah Brown married Lawrence Wood. Dinah was the daughter of Charles Brown and Susan Wood. She was named for the grandmother of Susan, who had been enslaved by Robert Darnall. [See Fishwick v. Sewall, and the post on Dinah’s Descendants] Dinah and her descendants were enslaved by the Robert Darnall and then devised to Robert Sewall and his heirs.

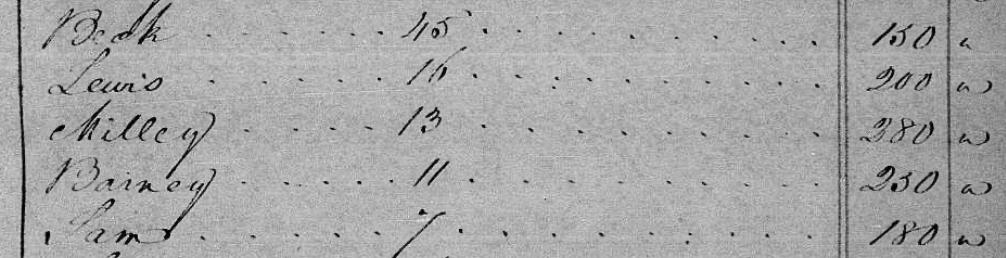

Dinah was listed as the youngest of Susan “Suck” Wood’s children in the 1853 Inventory of Robert D Sewall’s estate at “Poplar Hill”. Her age was recorded as 7; her estimated birth year was 1846.

Her marriage to Lawrence Wood was solemnized in January 1866 when she was 22 years old.

early marriage years

After their marriage, they lived near “Poplar Hill” and Dinah’s brother, Joseph Henry Brown, near the Catholic Church where Rosaryville would develop into a town. The first map is from Martenet’s Map of Prince George’s County in 1863. The second map is from Hopkin’s Atlas of Prince George’s County in 1878. The development of Cheltenham and Rosaryville results from the building of the railroad and the development of villages after emancipation.

In the 1870 census, they lived with their two children: Louisa and Buddy, and a teenager named Thorton. The 1870 census did not record relationships leaving us to infer relationships.

In the 1880 census, they are still living near Dinah’s siblings and her mother. They have an additional son, which they named after Lawrence. Dinah is working as a cook.

searching for Lawrence Wood prior to emancipation

Dinah’s family has strong ties to “Poplar Hill” and the “Woodyard”, her family having lived there since Susan’s grandmother was brought from Dorchester County prior to 1775, when Darnall moved to “Poplar Hill” with his step-daughter Jane Fishwick who had enslaved Dinah prior to Darnall taking possession of Dinah.

Lawrence does not appear in the 1853 inventory and his name, Lawrence is not one that appears in the 1821 inventories or other identified records related to “Poplar Hill”.

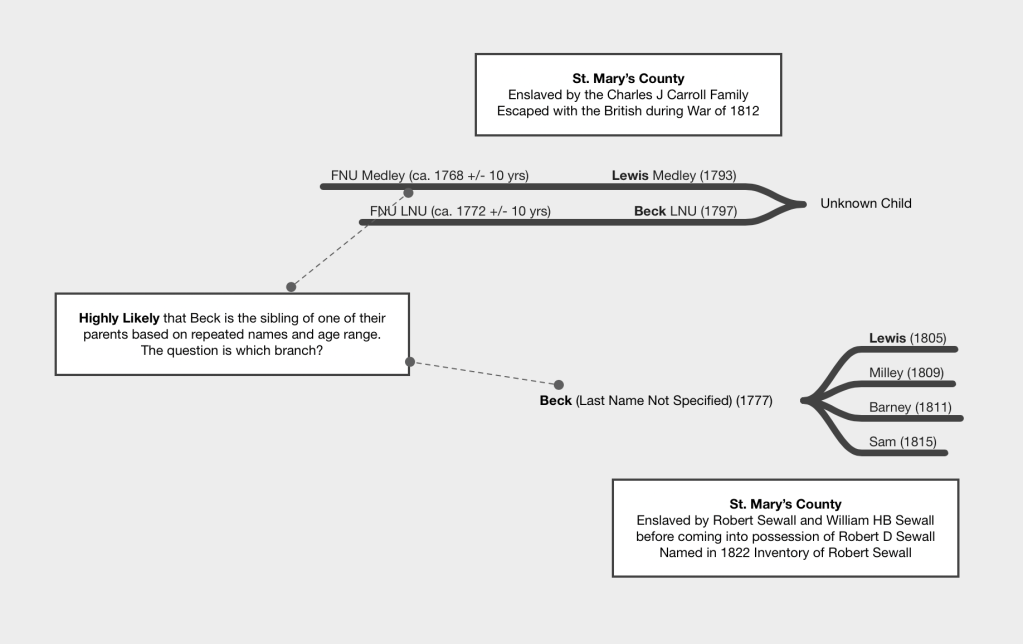

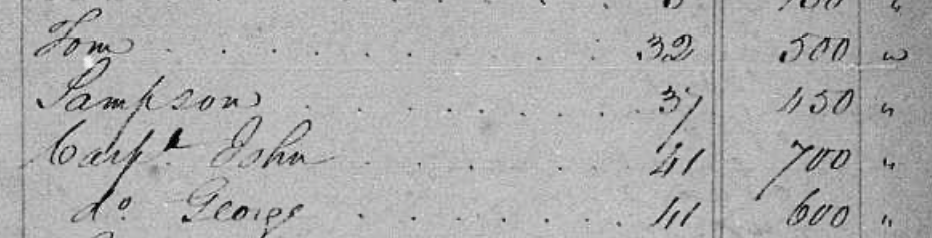

enslaved by Charles F Calvert

A “Lorenzo Wood” appears in the lists submitted to Prince George’s County Commission on Slave Statistics and compiled in 1867 & 1868. As enslavers had been been compensated for their “lost property” when the District had emancipated the enslaved in 1862, Maryland enslavers also hoped for compensation and many submitted lists to the commission. The Dangerfield family who owned “Poplar Hill” did not submit a list. However, Charles F Calvert submitted the name “Lorenzo Wood” along with sixteen other names.

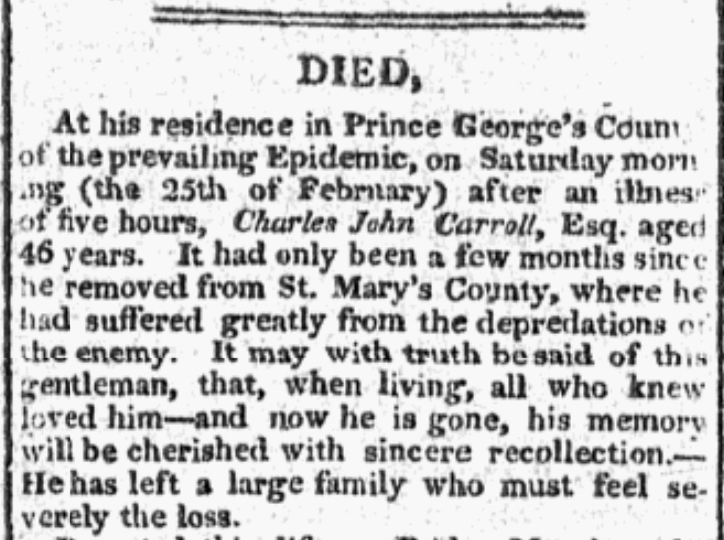

Charles F Calvert was descendant from “the Calverts”. He purchased the tract of land he called “Belle Chance” which situation on the north part of the land that would become Andrews Air Force Base in the 1840s. Prior to his purchase of “Belle Chance”, he is listed in the 1840 census near Wm. P Brinham and Joseph B Hill, suggesting he owned land near the southern edge of “Poplar Hill”.

Calvert, before and after his purchase of Belle Change” was a neighbor of the Sewalls and the Dangerfields at “Poplar Hill”. As evidenced by the “Early Records of White Marsh”, Sewall allowed the people he enslaved to enter into relationships on neighboring estates. 1828 Baptismal Records identifies the following relationships:

- James and Sarah were identified as husband and wife; James was enslaved by Arthur West and Sarah was enslaved by Sewall.

- Barney and Betsey were identified as husband and wife; Barney was enslaved by Jane Stone and Betsey by Sewall.

- Nicholas and Ann were identified as husband and wife; Nicholas was enslaved by Sewall and Ann by Joseph Hill.

The same may be possible for the Dangerfields who inherited “Poplar Hill” after 1853, allowing Lawrence “Lorenzo” Wood to meet Dinah Brown.

The list submitted by Calvert lists 4 people with the surname Wood:

- Betsy Wood, age 49

- Francis L. Wood, age 17

- Josephine Wood, age 15

- Lorenzo Wood, age 18

Lawrence Wood is listed as 27 in the 1870 Census records, nine years older than the age reported in the “Slave Statistics”. It is often ambiguous what age the enslaver used for the “Slave Statistics”. For example, Marsham Waring’s heirs used the same ages as on the early 1860s inventory compiled for his estate, even though the list suggests it represents their age at 1864. Others used their 1867 age. For Lawrence Wood and Lorenzo Wood to be within 9 years of each other suggests that they are the same.

The organization of his list makes it hard to tell if those with the same surname are closely related and if they are family groups. If we assume that they are, this suggests that Betsy Wood if the mother of the three teenagers.

Sources

Early Records of the White Marsh Church, Prince George’s County, Maryland. Bowie, MD: Prince Georges County Genealogical Society, 2005. Print.