Cedar Point sits at the mouth of the Patuxent River as it empties into the Chesapeake Bay in St. Mary’s County.

Its location was useful for the British during the colonial period as they established customs official there to collect taxes from the passing ships laden with tobacco. In the 18th century, the land was transferred into the Carroll family by way of marriage to Araminta Thompson, who was the illegitimate daughter of the customs official, and had been bequeathed the manor by her father, John Rousby II. [Collection on the Susquehanna estate, Carroll family, and Rousby family]

Charles J Carroll, son of Henry and Araminta [Thompson] Carroll, lived at the manor house, called Susquehanna, before and during the War of 1812. Its location was useful for the British in 1812 as well. The British navy plundered the estates on the waterways, and the manor on Cedar Point was exposed and the British took 5 of the people enslaved by the Carrolls with them, including Lewis and Beck Medley, husband and wife.

In 1828, the heirs of Charles J Carroll, applied for compensation for their lost chattel. The claim included “A lost of the [enslaved people] belonging to Charles John Carroll of the County of Prince George’s County and State of Maryland which were taken or carried away by the British from the mouth of the Patuxent River during the years 1813 + 1814”. [MSA]

In the claim, it is reported that Charles John Carroll, with Nicholas Sewall and Robert Holton boarded the British ship San Domingo in order to reclaim Adam, Phil and Sandy. Another deposition in the claim, mentions Lewis Medley and Beck Medley, the wife of Lewis Medley. They, too, went with the British and did not return to the Carrolls. In April 1814, the British had issued the Cochrane Proclamation:

To encourage further unrest, on April 2, 1814, Admiral Alexander Cochrane of the British forces issued a proclamation offering immediate emancipation to any person willing to take up arms and join the colonial marines. The proclamation also included the families of any person who joined the colonial marines and settled in British Colonies.”

Maryland State Archives

The claim recorded that Lewis and Beck Medley were on the list for Halifax. The Acadian Reporter issued announcements of ships that arrived in Halifax and it is estimate that 2000 refugees from slavery sailed to Nova Scotia between 1813 and 1816. Having escaped chattel slavery in the Chesapeake, the refugees in Halifax faced prejudice and resentment in Halifax at their arrival. [Nova Scotia Archives]

Lewis Medley, age 25, and his wife, age 21, with a child, is listed in the “Halifax List: Return of American Refugee Negroes who have been received into the Province of Nova Scotia from the United States of American between 27 April 1815 and 24 October 1818. [Nova Scotia Archives]

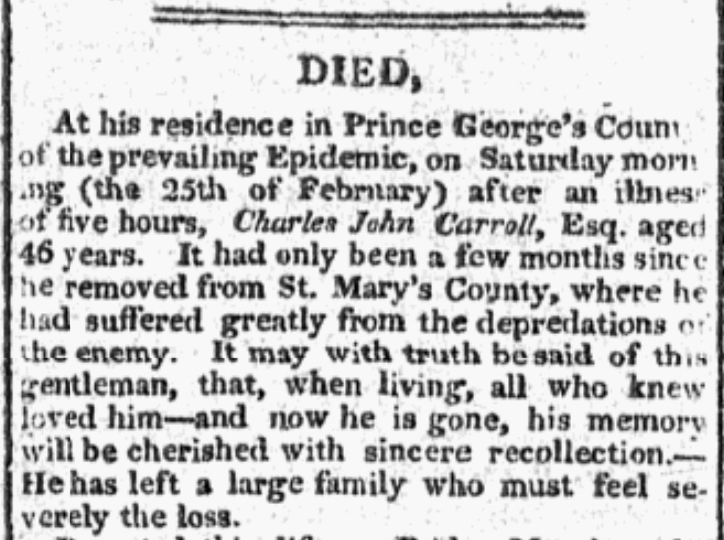

After the war, Carroll had moved to Prince George’s County, and had settled on the Patuxent River in the neighborhood of Nottingham, away from the British ships. Having escaped from the British, he died in 1815 from smallpox.

His children were raised by their grandmother, Araminta Thompson. His son, Michael B Carroll became a merchant and landowner; his daughter, Araminta Carroll, married John B Brooke, a wealthy lawyer, and settled at “Poplar Neck”, near Cheltenham and near the home of Robert Sewall of “Poplar Hill”.

Carroll-Sewall Connection

The Carrolls owned Susquehanna on Cedar Point in St. Mary’s County and were neighbors to the Sewalls, of Mattapany Sewall. Both families were prominent Catholic families with connections to power in colonial and early National Maryland.

Nicholas Sewall, who boarded the ship with Charles J Carroll, was a cousin of Robert Sewall, who had inherited “Poplar Hill” from the Darnalls. The Sewall’s owned land on Cedar Point throughout the 1700s.

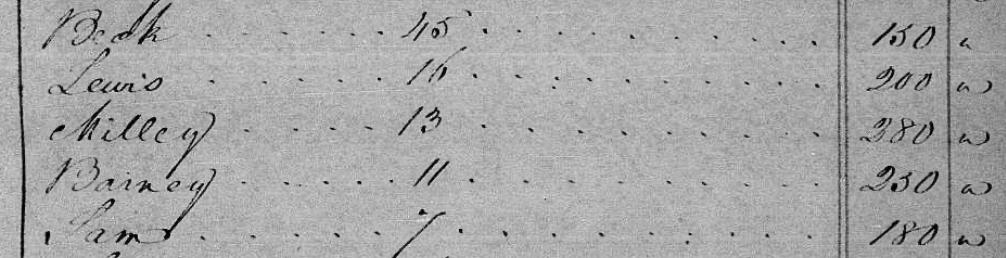

When Robert Sewall died in 1820, he had land in both Prince George’s County and St. Mary’s County. As a result, he had two inventories. In the inventory for St. Mary’s County, he included the names of the enslaved people on the property [TT 5:25]. Among them was a family group including an inferred mother, Beck (45), and her children, Lewis (16), Milley (13), Barney (11), and Sam (7).

This raises the question, as often names repeat across generations, if Beck and her son Lewis were kin to the Lewis and Beck who went with the British. Their enslavers were connected to each other politically, religiously and geographically.

| 1814 Claim | 1822 Inventory |

|---|---|

| Lewis Medley, 21 [1793] | Beck, 45 [1777] |

| Beck Medley, 17 [1797] | Lewis, 16 [1806] |

| Milley, 13 [1809] | |

| Barney, 11 [1811] | |

| Sam, 7 [1815] |

Based on the given ages of the people in the two documents, estimated birth years can be given and from that, possibilities for kinship emerge. The Medley’s may be cousins to Beck’s children, either of their parents would have been in the same generation of Beck. Both Beck and the unknown parents could have used family names for their children. Or, Beck Medley, may be the daughter of Beck, as Beck would have been 20 when Beck Medley was born.

Alternatively, the reappearance of “Lewis” in both family groups could be because Lewis was a family name used by the Sewalls (see Nicholas Lewis Sewall, from whom Robert Sewall bought Mattapany Sewall) and the enslavers provided their own name to their enslaved.

Note on Plantation Size

Charles J Carroll died in 1815. His inventory was submitted to Prince George’s County County and included 11 names [TT 5:9] . Unlike Sewall’s inventory which appeared to be organized by family groups, Carroll’s is organized by age.

Carroll enslaved far fewer people than Sewall, which suggests that family groups were not sustained. In “Tobacco and Slaves”, Allan Kulikoff describes how enslavers with fewer people in captivity were less likely to sustain family groups. [See Chapter 9: Beginning of the Afro-American Family] He describes how [enslavers] would keep “women and small children together but did not keep husbands and teenage children with their immediate family” and that enslavers with small farms [enslaved less than 11 people] separated enslaved people “more frequently than those on large plantations” to pay debts or through bequeathals. This may explain why Sewall’s inventory was organized by family group and Carroll’s was not.

Of the five people who escaped with the British, there were four different surames: Barnes [Adam], Jackson [Philip], Lewis [Sandy], and Medley [Lewis]. This suggests Carroll bought enslaved people from other plantations and brought them to Susquehanna for labor. Kulikoff’s research into Chesapeake enslavers and the people they enslaved suggests that “cross-plantation” kin groups were established as often the enslaved were sold to and by neighboring enslavers.

The British took the four adult men with them, when they raided Susquehanna, as the 1815 inventory only lists males who are children: George, 10, Lewis, 6, Davy, 5.

1 Comment