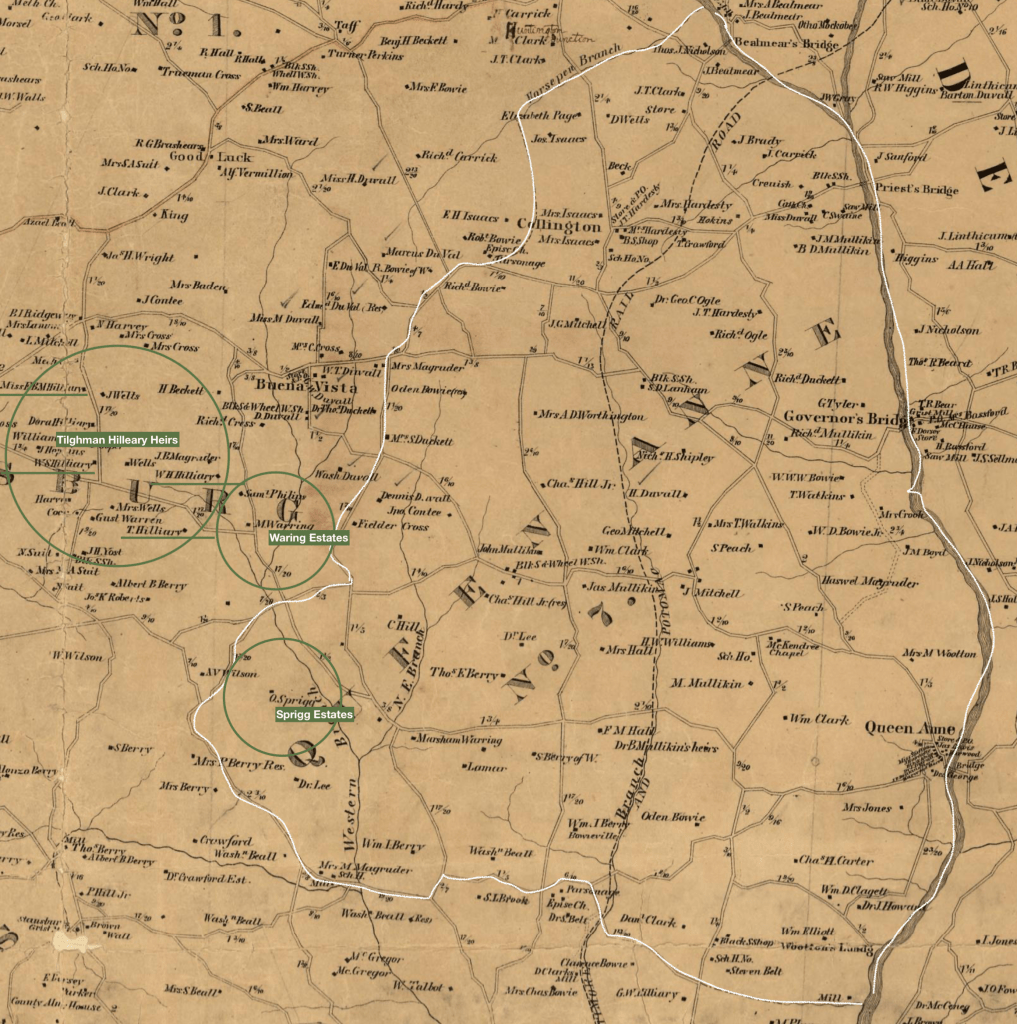

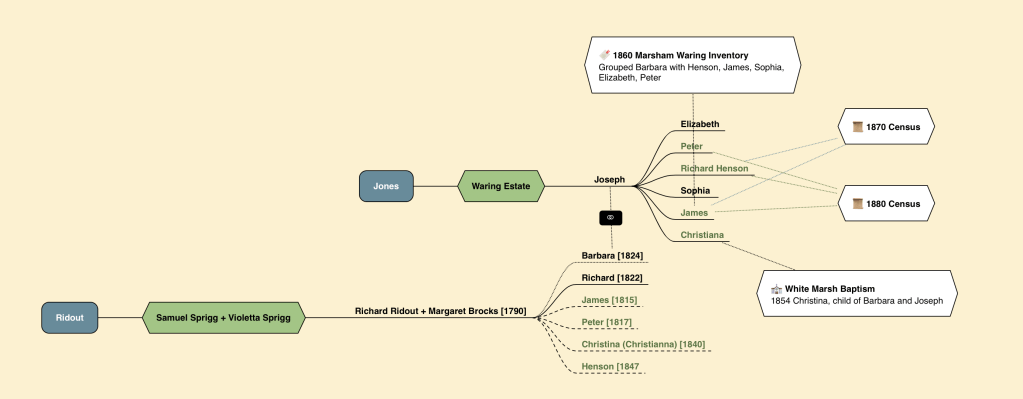

Joseph and Barbara had several children and lived on the Waring estates.

A White Marsh baptism record from 1854 gives a clue to her family before her union with Joseph. The priests recorded her family name as “Reyder”. Given the phonetic spelling of the priests who were not English, it suggests the possibility of Barbara being related to the Ridout family.

Peter and Priscilla Ridout, Inferred Brother

In the 1867 Commission on Slave Statistics, the estate for James Waring (dec.) submitted a compensation list that included other Ridouts:

| Family Name | Given Name | Age |

|---|---|---|

| Ridout | Priscilla | 37 |

| Ridout | Eliza | 22 |

| Ridout | Henny | 2 |

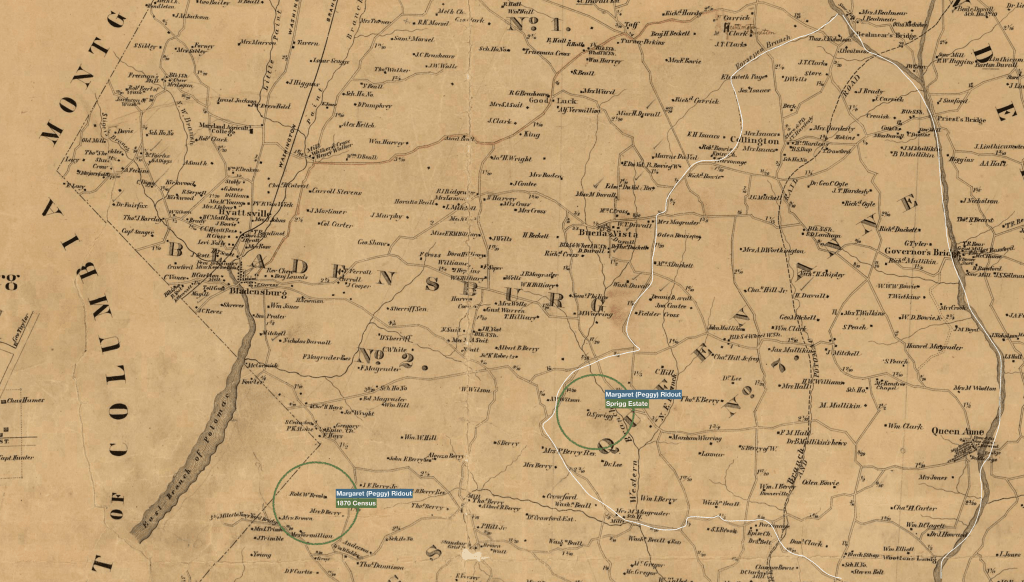

In the 1870 Census, Priscilla can be found in a household with Peter Ridout, which suggests that Priscilla’s family name is not Ridout, but adopted upon her union with Peter. Peter appears on a compensation list submitted by Violetta Sprigg, the widow of Samuel Sprigg, the former governor of Maryland. In 1870, Peter and Priscilla are living in Bladensburg, next door to Charles H Hays. They are also living within the vicinity of Alex McCormick, Barbara Jones’ neighbor in 1870.

In 1880, Peter and Priscilla have moved into the District along Central Avenue, just as Joseph and Barbara have moved from McCormick’s farm to Central Avenue. Joseph and Barbara Jones are enumerated at household 169, while Peter and Priscilla are enumerated at household 171.

The likelihood of Peter and Barbara being siblings is based on a few things.

- Joseph and Barbara named one of their sons Peter, who would continue to live in the District near Central Avenue into the 20th century. It would appear they named Peter after Barbara’s brother Peter.

- Peter and Barbara’s estimated birth years: Barbara has an estimated birth year of [1829] based on the 1870 census, while Peter has an estimated birth year of [1817]. They are approximately 12 years apart; this difference falls within the range of a woman’s typical child-bearing years of 15-45 (or 30 years).

- Their geographic proximity to each other both prior and after emancipation. They resided on neighboring estates and left the immediate vicinity of the estates after emancipation and lived near each other after emancipation.

Ridouts of Sprigg’s Northampton Estate

Violetta Sprigg submitted not only the name of Peter Ridout to the 1867 Commission on Slave Statistics, but also the names of other Ridouts.

| Family Name | Given Name [Name] | Age |

|---|---|---|

| Ridout | James | 50 |

| Ridout | Peter | 48 |

| Ridout | Peggy [Margaret] | 66 |

| Ridout | Hanson | 18 |

| Ridout | Christianna [Christina] | 25 |

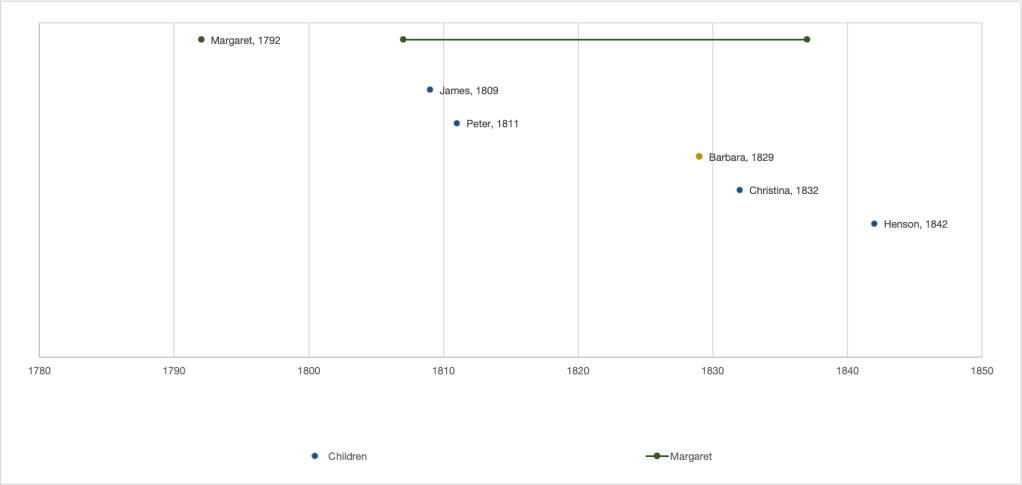

Based on her age, Margaret (Peggy) Ridout is assumed to be the mother of the family group. The chart below was created to evaluate the likelihood that Margaret (Peggy) is the mother of the other Ridouts.

Using Margaret’s birth year, we can estimate her child-bearing years as when she was 15-45. In the 1870 census, Margaret (Peggy) Ridout is listed as 80 years old, which indicates it’s likely an estimated age, though it places her birth year as 1790. In the 1867 Prince George’s County Slave Statistics, she is 66, giving her an estimated birth year of 1801, a full decade later; while in Samuel Sprigg’s 1855 inventory, she is listed as 63, giving her an earlier estimated birth year of 1792, closer to her 1870 census age. For purposes of the chart, we will use the ages in the 1855 inventory, as it appears that the compiler of the compensation lists for the Prince George’s County Slave Statistics used the ages in the inventory.

Margaret is shown with her birth year mark and a line drawn to represent her child-bearing years, and her children’s estimated birth years are plotted as well. James and Peter appear to have been born toward the beginning of her child-bearing years while Christina was born later in her years. Henson falls outside of the 15-45 year range, though within a margin of error of five years.

In 1870, Margaret has also left the Sprigg estate and moved closer to the District. She is living in the household of [Geo R] Wilfred Marshall, a neighbor of Robert W. Brooke.

Also living in the household is Christy Ann [Christina] Beall. She is 35 years old with an estimated birth year of 1835, which suggests she is Christina (Christianna) Ridout, the inferred granddaughter of Margaret (Peggy) Ridout and is confirmed by her son’s death certificate. In 1911, Daniel Bell (Jr.) died in New York City, where he had migrated and was working as a driver. His death certificate lists his parents as Daniel Bell and Christina Ridout.

In 1822, the priests of White Marsh recorded a baptism of Richard, the son of Richard Ridout and Margaret Brockx [sic]. The transcriber proposed the family name Briscoe in brackets. However, based on the family names of other people enslaved by the Spriggs in the 1867 Prince George’s County Slave Statistics, I suggest the surname Brookes. This will be explored further in a different post.

Patterns in Given Names

When looking at the given names of the enslaved, it is ambiguous who gave the name. Was it the parents, or was it the enslaver?

When looking at names of those born within the 18th century, and especially earlier in the century when Maryland planters were importing larger numbers of Africans to labor on their fields, it is more likely the names were imposed on the Africans by the Marylanders. In later generations, especially after the abolishment of the international slave trade in 1808, the names originally given by the Marylanders to the first generation of African appear to be given to their African-American descendants by their parents and grandparents as a way of marking kin groups within a world that cared little for their families and relationships.

The identified generations of Ridouts have names that repeat across the generations, suggesting kin groups.

Generation 1

Two white-generated source documents allow us to identify the first generation of Ridouts living in the vicinity of the Waring/Sprigg estates along the Western Branch of the Patuxent River:

- the White Marsh baptism record that identifies Margaret’s (Peggy) partner as Richard

- a War of 1812 claim for two enslaved people (more about War of 1812 claims in general can be read about on the Maryland State Archives site)

In 1828, Tilghman Hilleary, a neighbor of Marsham Waring, sought compensation for the Andrew and Peter Ridout, who runaway from the Hillearys during the War of 1812.

Born before 1808, it is possible that Richard, Andrew and Peter were forced to migrate from Africa to Maryland as laborers. However, due to a common family name, it is likely that Peter, Richard and Andrew are born in Maryland to enslaved Africans or African-Americans. Their exact relationship to each other is unknown; the common family name suggests brothers or cousins. Given the few number of Ridouts identified in the Prince George’s County records (e.g., the Prince George’s County Slave Statistics, the White Marsh Baptism records, the 1870 census), it seems more probable that they are brothers, rather than cousins, from a father brought to Prince George’s County by his enslaver (either by the Hilleary or Sprigg families, who appear to be an intertwined family themselves in previous generations).

Peter’s name gets repeated in later generations.

| Generation 1 Names |

|---|

| Peter |

| Andrew |

| Richard |

Generation 2

Shifting to the second generation, or specifically the children of Richard Ridout and Margaret (Peggy), we can identify the children from the Samuel Sprigg Inventory, the Prince George’s County Slave Statistics and the White Marsh records. No doubt there are as yet unidentified children of Richard and Margaret.

Of note, Richard and Peter are repeated. Richard (Jr.) is mostly named after his father, while the use of Peter for their other son, suggests that Peter (Sr.) was a close relative. The use reinforces the idea that Peter, Andrew and Richard of Generation 1 were brothers.

| Generation 2 Names |

|---|

| Peter |

| James |

| Richard |

| Henson |

| Christina |

| Barbara |

Possible Generation 2

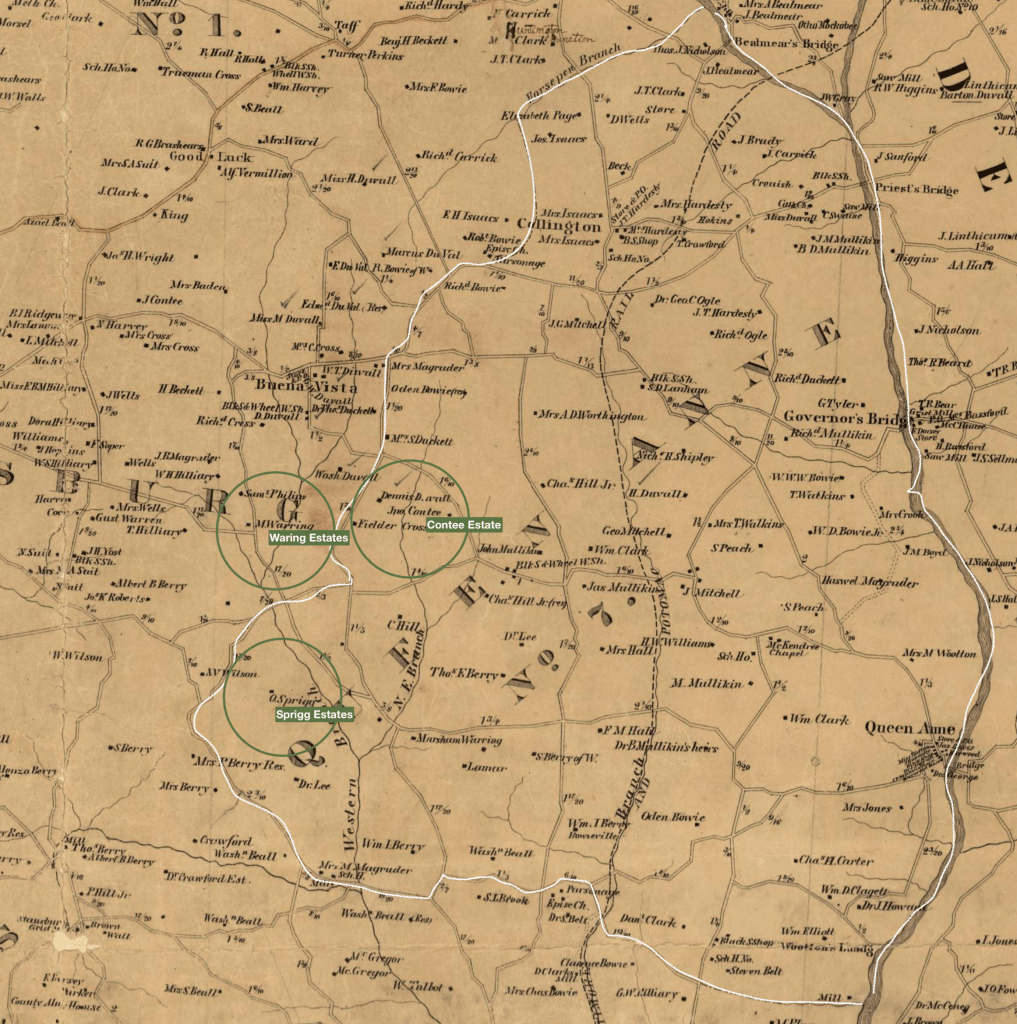

One of the possible unidentified children of Richard and Margaret may be the partner of Sophia Ridout, claimed by John Contee’s administrator in the Prince George’s County Slave Statistics. She may also be partnered with either James or Richard. No other records related to Sophia and her children have been identified. Contee’s list did not name an adult male Ridout, suggesting that he may have been enslaved on another estate, leaving open the possibility that he was James, Richard, and Henson.

She uses the name Richard (Dick) for her son, likely named for either his father or uncle.

Contee’s estate was in the same neighborhood of Waring and Sprigg.

Generation 3

This generation brings us to Barbara (Ridout) Jones, who initiated the line of inquiry. She was identified in the White Marsh record as Barbara Reyder. The names of her children reinforce the idea that she was a Ridout descended from Richard and Margaret.

The use of White Marsh Baptism Records, the Prince George’s County Slave Statistics, and the 1870 & 1880 Census records allows us to identify the following children for Barbara (Ridout) Jones:

Four out of six of Barbara’s children share the names of her inferred siblings. The fifth child, Sophia, shares a name with the inferred sister-in-law, Sophia, who lived with her children on the neighboring Contee estate.

| Generation 2 Names | Generation 3 Names |

|---|---|

| Peter | Peter Jones |

| James | James Jones |

| Richard | Richard Henson Jones |

| Henson | Richard Henson Jones |

| Christina | Christina Jones |

| Barbara |

Tentative Conclusion

The use of repeated given names across generations; the proximity to other Ridouts on neighboring estates, along with proximity after emancipation as they congregated toward Seat Pleasant and Lincoln suggests that Barbara was a child of Richard and Margaret Ridout.