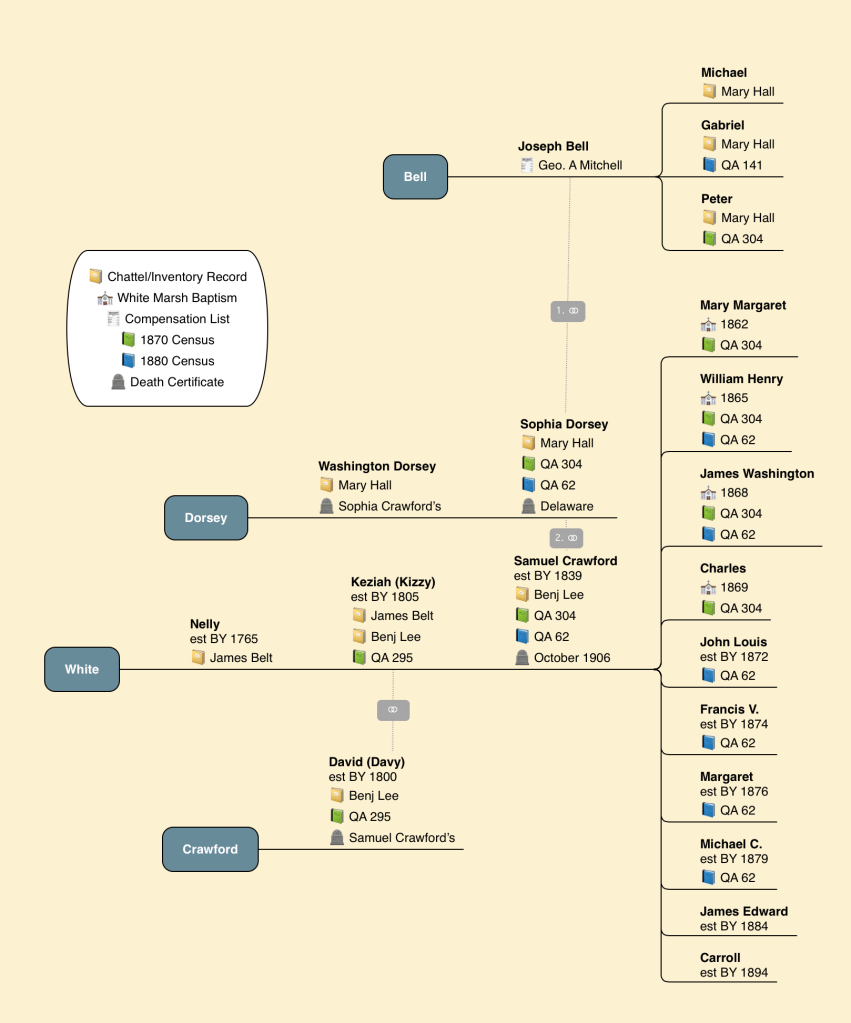

In the 1863 Inventory of Benjamin Lee‘s estate, Sam, age 24, is listed two names below the name of Davy and Kizzy. No other details are recorded for him. The estate’s appraisers noted that “Owning to the unsafe conditions …. produced by the war” that raged on, they could not provide a market value for the people they commodified, marking only each person as $100, giving no other indication of health or skill. In October 1864, the Civil War Draft called the name of Samuel Crawford, “slave of the estate of Benj Lee”; based on the birth years of his children, he likely did not get called up.

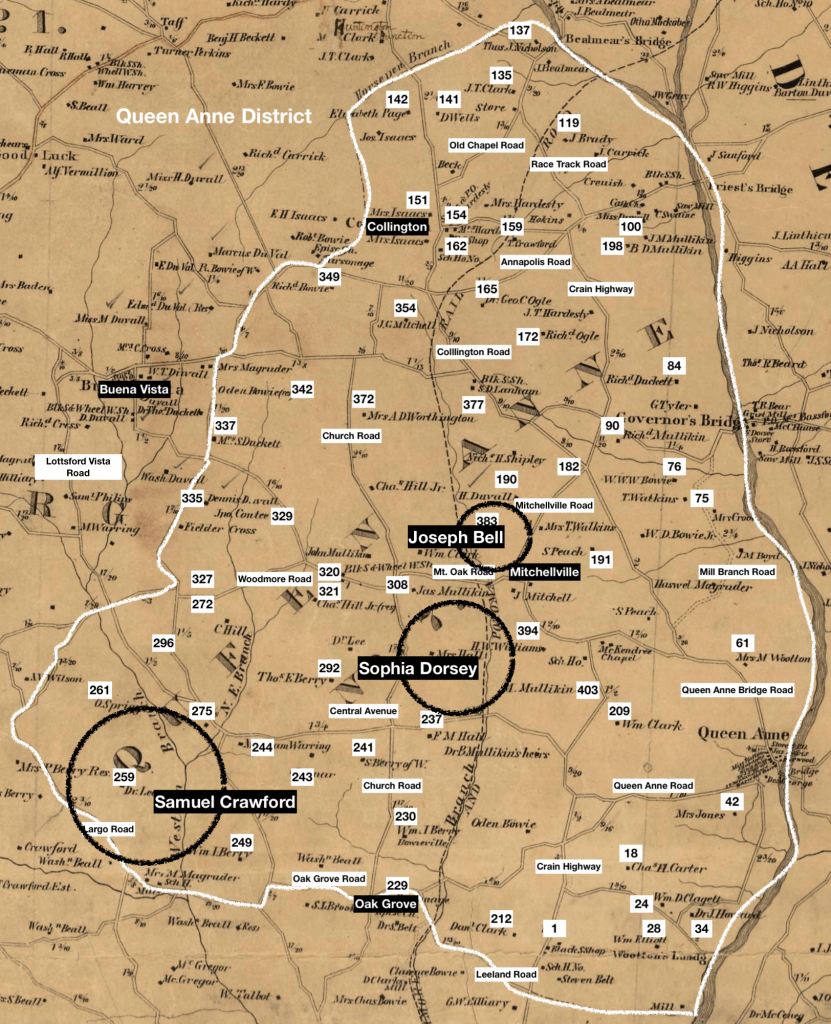

And in 1870, after the Civil War ended and the nation began the slow arduous work of reconstructing an economy based on a strict social hierarchy, Samuel Crawford, age 35, was living between Buena Vista and Mitchellville, two small mercantile communities among the plantations of the “Forest of Prince George’s County.”

Crawford lived near the convergence of Woodmore Road with Mt. Oak Road at Church Road near the estates of Mary Hall and James Mullikin, white landowners who had connections with some of the richest men in Prince George’s County, that derived their wealth from the labor of the enslaved and near Lee’s newly purchased Stewart Farm.

Samuel Crawford is living with his wife, Sophia Crawford, age 30 and their four children, Mary, age 8, William, age 5, Washington, age 3, and Charles age 1. Also living with them is Peter, age 10, not listed chronologically with the other children, suggesting a different relationship than biological.

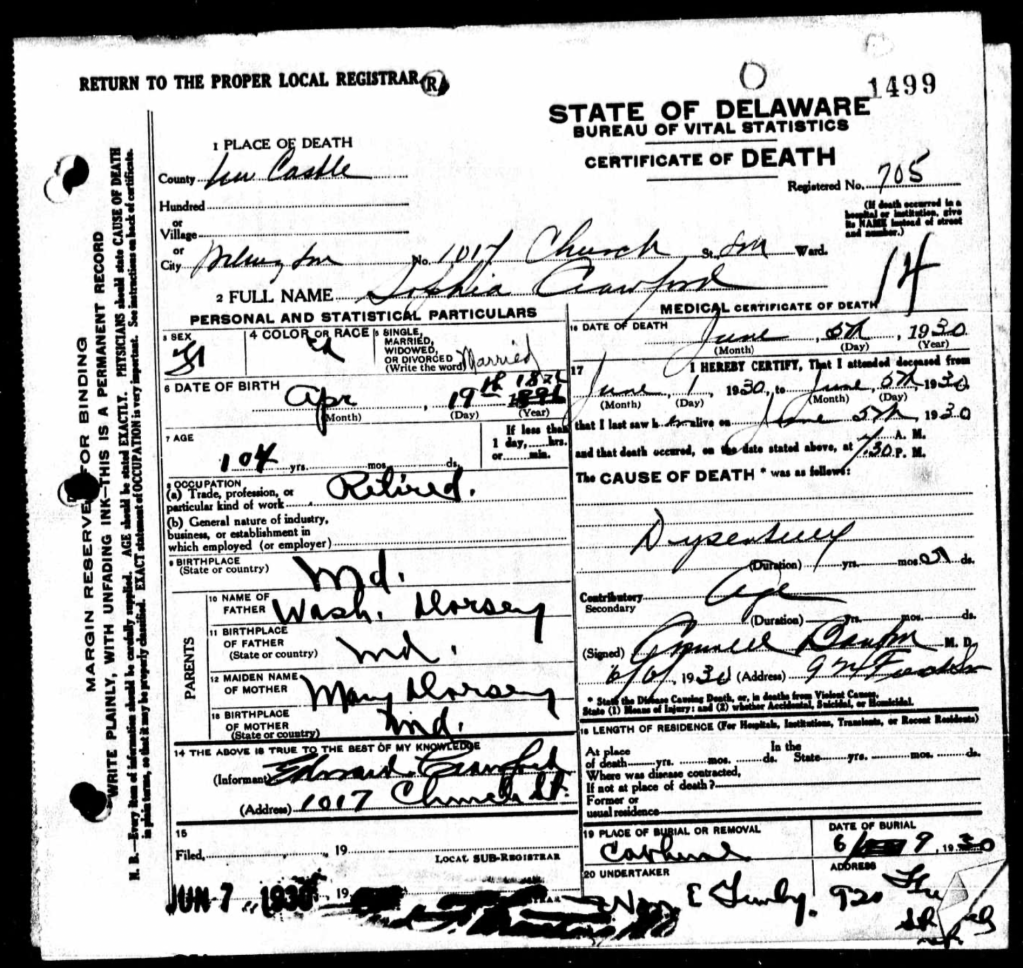

Through the next three decades, Samuel would labor in the fields of Queen Anne District, renting his farm and providing for his family. He died in October 1906 from chronic gastritis. His son provided the information for the Certificate of Death, naming Sophia as his wife and David Crawford as his father. After his death, Sophia and many of their children migrated north away from Queen Anne District and Prince George’s County to Delaware.

White Marsh Baptisms

Sophia died a few decades later in 1930. At the beginning of the Great Depression, Sophia Crawford lived in New Castle, Delaware, where she was living with her son, Edward. He gave the name of her parents as Wash. Dorsey and Mary Dorsey of Maryland for the death certificate.

The Evening Journal ran an obituary for her: “Former Slave Dead at Age of 104”

Life as a slave in Maryland, the Civil War and freedom which followed it, were vivid memories of Mrs. Sophie Crawford, who died last evening, at the age of 104 years, at the home of her son, James E. Crawford, 1017 Church Street. She had not been ill, but gradually weakened until she died.

She was born on April 19, 1826 on the estate of the late Mr. and Mrs. F. M. Hall in Prince George county, MD., and spent her life as a slave there. Sophie Dorsey married Joseph Bell when she was eighteen years old. Two sons that marriage, Gabriel Bell of Uniontown, PA., and Peter Bell of Baltimore, still survive her. Joseph Bell was killed in the Civil War. In 1865, she married Samuel Crawford. Eleven children were born to them, six boys and five girls. Of these children, John L. Crawford, Michael C. Crawford, and James E Crawford, all of this city, survive her.

The old colored woman had been reared a Catholic and since coming to Wilmington in 1911, was a member of St. Joseph’s parish. She was very devout and counseled her children to be temperate in all things.

Funeral Services will be held on Monday from her home. Solemn requiem mass will be said in St. Joseph’s Church and internment will be in Cathedral cemetery.

The News Journal, Wilmington, Delaware, 6 Jun 1930, page 39

The article notes her former enslaver. Mrs. F. M. Hall, or Mary Hall, was part of the Hill family, descendant from the Darnalls and other Catholics connected with the Calvert family, who had shaped much of Maryland’s culture and economy. Mary Hall, the widow of Francis Magruder Hall, had inherited a vast estate not only from her husband, but both of her parents, Clement and Eleanor Hill.

Connected as she was to the wealthy Catholic landowners, she also had connections to the White Marsh Jesuit Plantation near Priest’s Bridge in Queen Anne District along the Patuxent River. The priests of White Marsh baptized many of the Catholics living in Queen Anne District, both the white landowners and those they enslaved. The Jesuits kept records of their baptisms, noting often who enslaved the mother of the baptized child. Due to a fire in 1853, earlier records are incomplete with mostly only those from around 1820 preserved. “White Marsh Book 3” kept the records of the baptisms after 1853 and the fire. Among them, Samuel and Sophia Crawford had four children baptized and their sacrament recorded in the records of the Jesuit Priests.

- In 1862, one year after the death of Mary Hall, Sophy Dorsey and Samuel Crawford had their daughter Marg. baptized. Sophy’s sister, Rosanna, sponsored the child. No enslaver is noted.

- In 1865, as the Civil War drew to an end and after Maryland ended slavery, Saml. and Sophia Crawford had their son, William Henry, baptized. Harrietta Mitchell sponsored the child.

- In 1868, Jas. Washington, the son of Sam. Crawford & Sophy, his wife, is baptized. Harriette Hall is the sponsor. The baptism occurred at Dr. Belt’s, a relative of Benjamin Lee. The same day, Sophy Crawford sponsored the baptism of Jas. Henry, the son of Philip Hall and Harriette, his wife, who had stood as sponsor for their children.

- In 1869, Charles, the son of Samuel Crawford & Sophia Dorsey, his lawfull wife was baptized. Lowis [sic] Wood sponsored the baptism.

No record of their marriage has been found.

The four children baptized at White Marsh are the same four children listed in the 1870 census. Another White Marsh record provides clarity for the relationship of Peter, age 10 in the census.

Her obituary notes eleven children for Samuel and Sophia, six boys and five girls. Reviewing the 1870, 1880, 1900, and 1910 census, this does not seem to be accurate.

- 1870 Census: 1 girl and 3 boys

- 1880 Census: 2 additional girls and 2 additional boys, for 3 girls and 5 boys total

- 1900 Census: 2 additional boys, for 3 girls and 7 boys, for 10 total.

The 1900 census also marked 13 children total which would account for the 3 boys with Joseph Bell (see below) and 10 children from Samuel, with seven children living. The 1910 census also marked 13 children total with 10 children living.

Peter Dorsey Bell

In 1859, three years before the death of Mary Hall, Peter was baptized, the son of Joseph Bell and Sophia Dorsey, illeg.; the baptism was sponsored by William Weldon and the baptism occurred “at Mrs. Hall’s.”

Peter is the step-son of Samuel Crawford and the son of Joseph Bell and Sophia Dorsey. While marriage was not legally recognized by the state between enslaved people, and while slaveholders did not often recognize the rights of those partnered, the records of White Marsh show that Mrs. Hall had permitted and perhaps even encouraged a Catholic blessing for the unions of those enslaved by herself and her neighboring Catholic slaveholders. This suggests that the union between Joseph and Sophia Dorsey was not one sanctioned by Mary Hall or the other white slaveholders, though Sophia viewed it as a legitimate partnership.

Another record, in 1858, records the baptism of Gabriel, son of Sophey “of Mrs. Hall’s”. No father was listed. In 1880, there is a Gabriel Beall living in Queen Anne District who was estimated to have been born in 1858.

In Mary Hall’s 1861 Inventory, Sophy, age 24, is listed with her parents, Dorsey, 45, and Mary 40, and their family group is listed with Peter, age 1, and Gabriel, age 3. There is also a Michael age 5, suggesting that Sophy may have had another son, named Michael. She would later name another of her sons with Samuel Crawford, Michael.

Joseph Bell was enumerated by Geo. A. Mitchell in the 1867 Compensation Lists submitted to the Prince George’s Commission on Slave Statistics. Mitchell owned land on the east side of Collington Branch near the Mullikin’s and Halls. In the 1870 census, Mitchell was marked as a Merchant and Farmer and it is his name that was given to the community that grew after the war with the establishment of the railroad nearby. The article notes he was killed in the Civil War; a service record has yet to be located for him.