a man Undone

merchant of queen anne

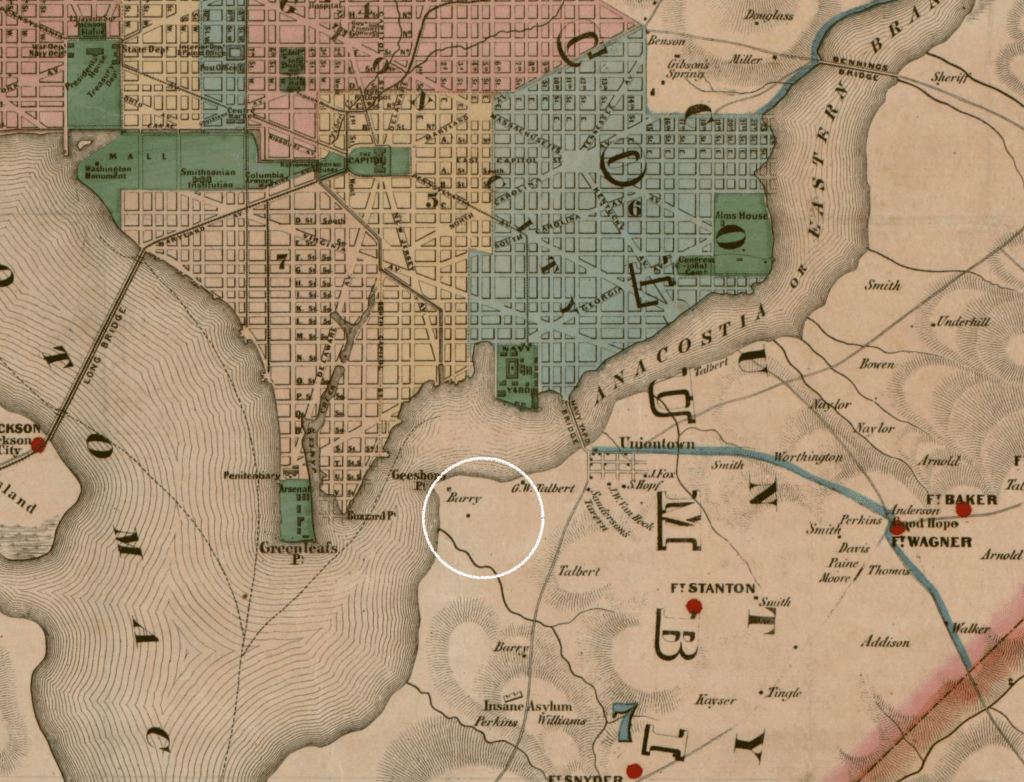

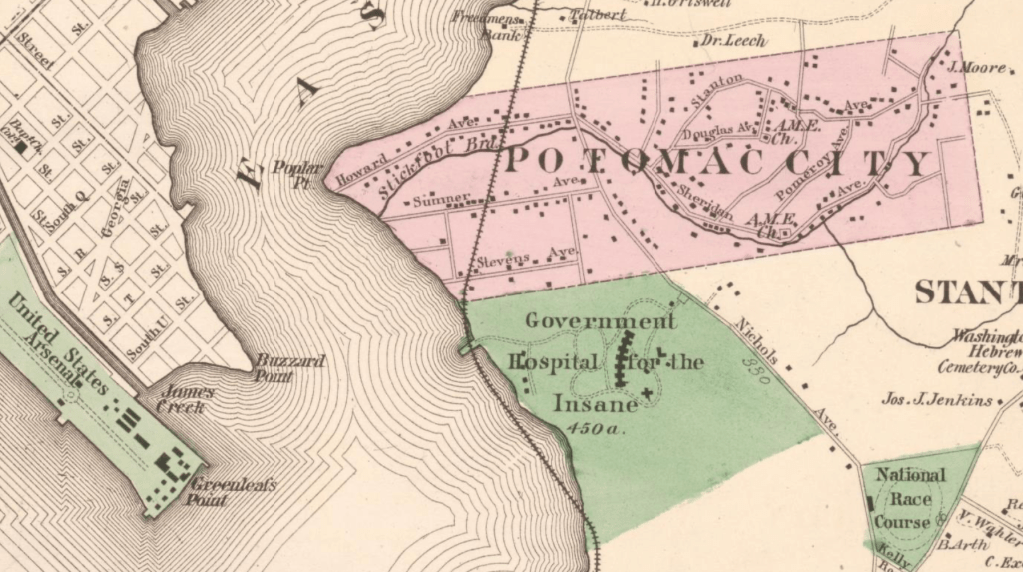

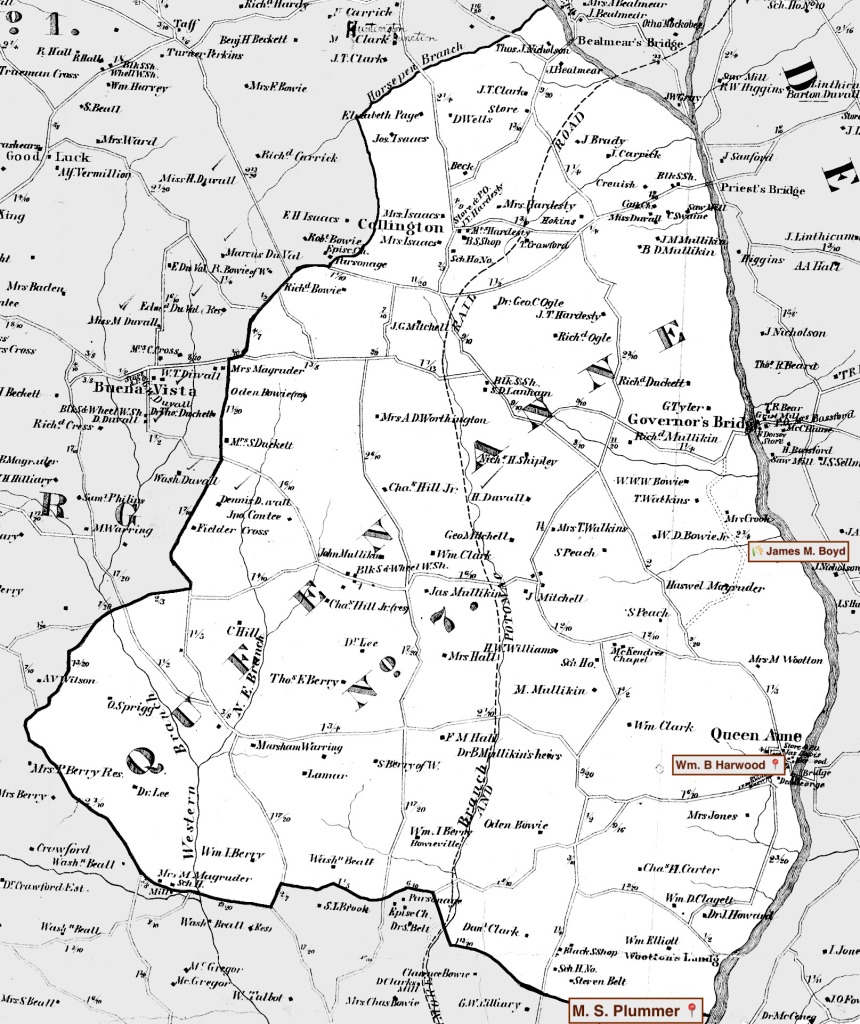

William B. Harwood operated as a merchant in Queen Anne on the Patuxent River during the 1850s. The 1850 census enumerated his household, including a wife and child, and recorded his modest real estate valued at $1,200, likely a town lot and store. An 1852 Bill of Sale documents his role as a purveyor to the local planter class, detailing a substantial sale to Haswell Magruder of dry goods, spirits, groceries, and 1,000 cigars. Yet, by 1857, Harwood was insolvent, unable to pay his creditors.

Transcription of Insolvent Notice

INSOLVENT NOTICE.

PRINCE GEORGE’S COUNTY, TO WIT:

ON application to the subscriber, Judge of the Circuit Court for Prince George’s County by petition in writing of WILLIAM B. HARWOOD, of said county, stating that he is in insolvent circumstances and unable to pay his debts, and praying for the benefit of the act of the General Assembly of Maryland, entitled “An act for the relief of insolvent debtors,” passed at January session, eighteen hundred and fifty-four, on the terms therein mentioned, a schedule of his property and a list of his creditors on oath, as far as he can ascertain the same, being annexed to his petition; and the said WILLIAM B. HARWOOD, having taken the oath by the said act prescribed, for the delivering up of his property, and given sufficient security for his personal appearance at the Circuit Court for Prince George’s County to answer such interrogatories and allegations as may be made against him; and the said WILLIAM B. HARWOOD, having further made oath, that he has not, at any time, sold, lessened, transferred or disposed of any part of his property, for the use and benefit of any person or entrusted any part of his money or other property, debts, rights or claims, thereby to delay or defraud his creditors or any of them, or to secure the same, so as to receive or expect to receive any profit, benefit or advantage himself therefrom; and having appointed JAMES M. BOYD his Trustee, who has given bond as such, and received from the said WILLIAM B. HARWOOD a conveyance and possession of all his property, real, personal and mixed—I do hereby order and adjudge that the said WILLIAM B. HARWOOD be discharged; and that he give notice to his creditors by causing a copy of this order to be inserted in some newspaper published in Prince George’s County, once a week for three consecutive months, before the next November Term of said Circuit Court, to appear before the said Circuit Court, at the Court House of said County at the said Term, to show cause if any they have, why the said William B. Harwood should not have the benefit of said act as prayed.

Given under my hand this eighth day of June, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and fifty-seven.

PETER W. CRAIN.

True copy—Test: CHARLES S. MIDDLETON, Clerk.

June 10, 1857—3t [Planters’ Advocate]

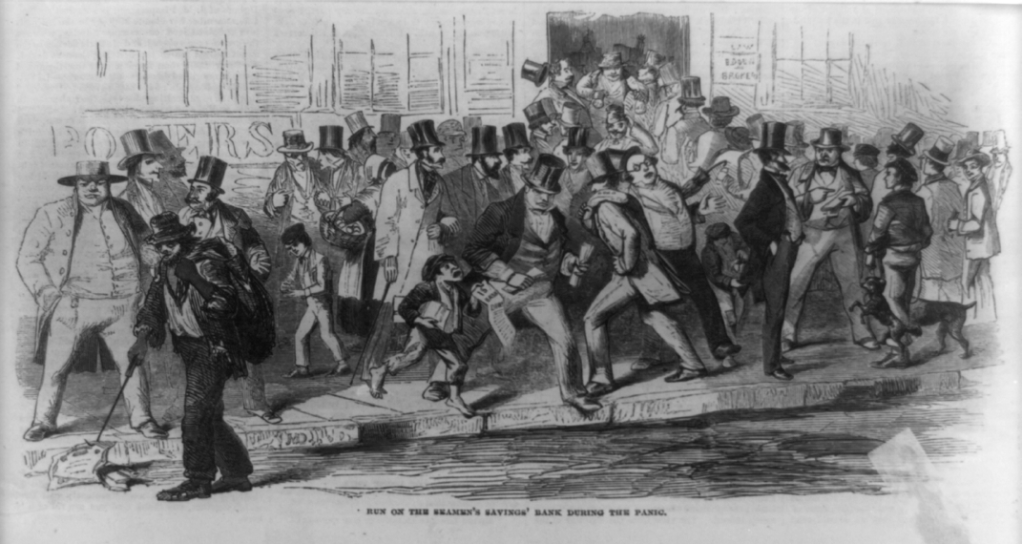

Despite his established business, the economic pressures that precipitated the Panic of 1857 proved insurmountable. The panic was fanned by overspeculation, falling grain prices after the Crimean War, and tightening credit. Harwood, a merchant in Queen Anne, would have been reliant on credit and the local farmers ability to pay their bills. Falling crop prices and credit crisis would have crushed his ability to navigate the market, leading to his unpaid debts. By June 1857, Harwood petitioned the Circuit Court, declaring himself insolvent and unable to pay his creditors.

a trustee’s ledger: seizing a merchant’s accounts

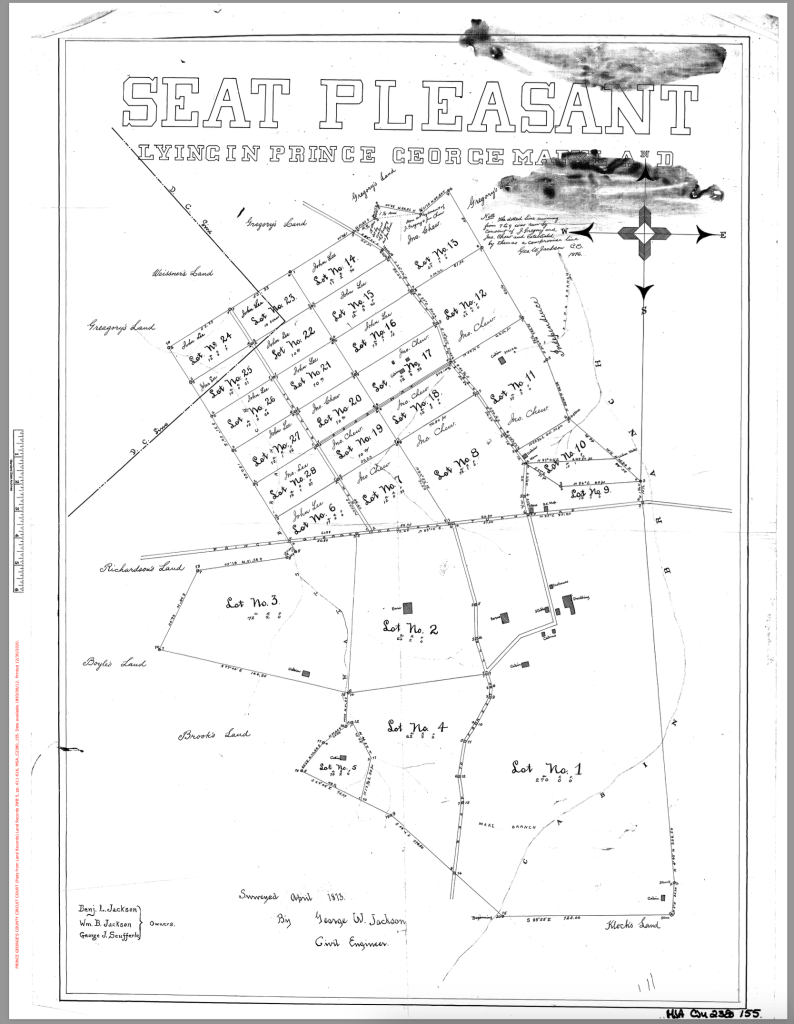

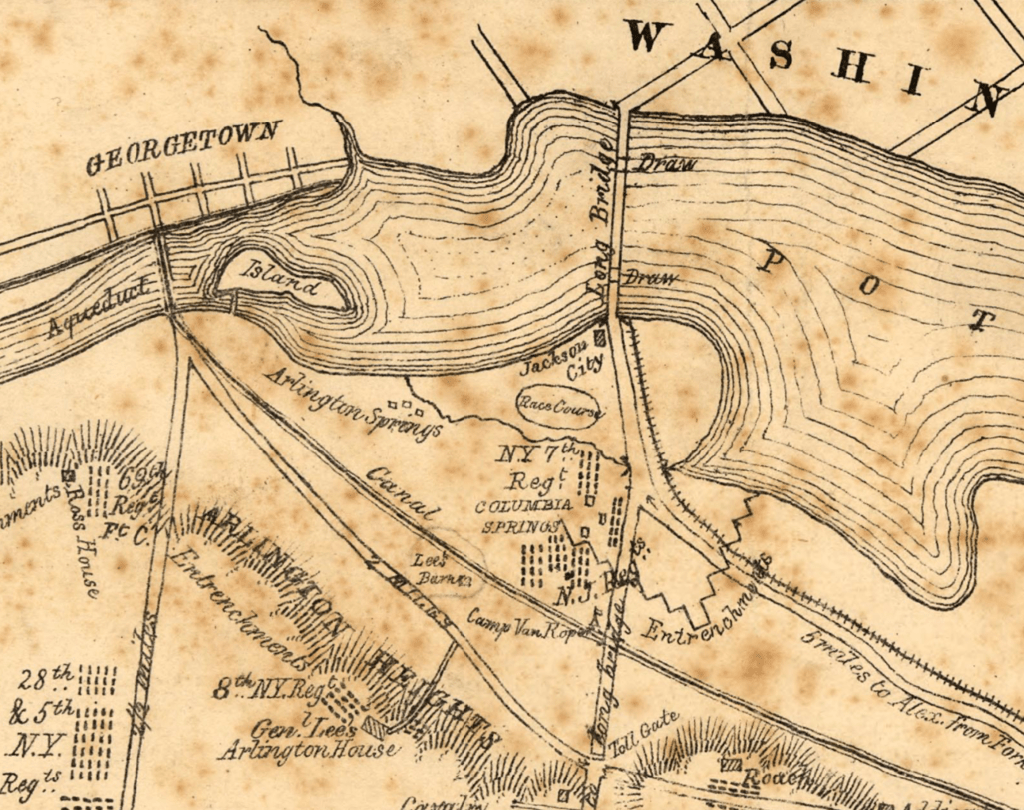

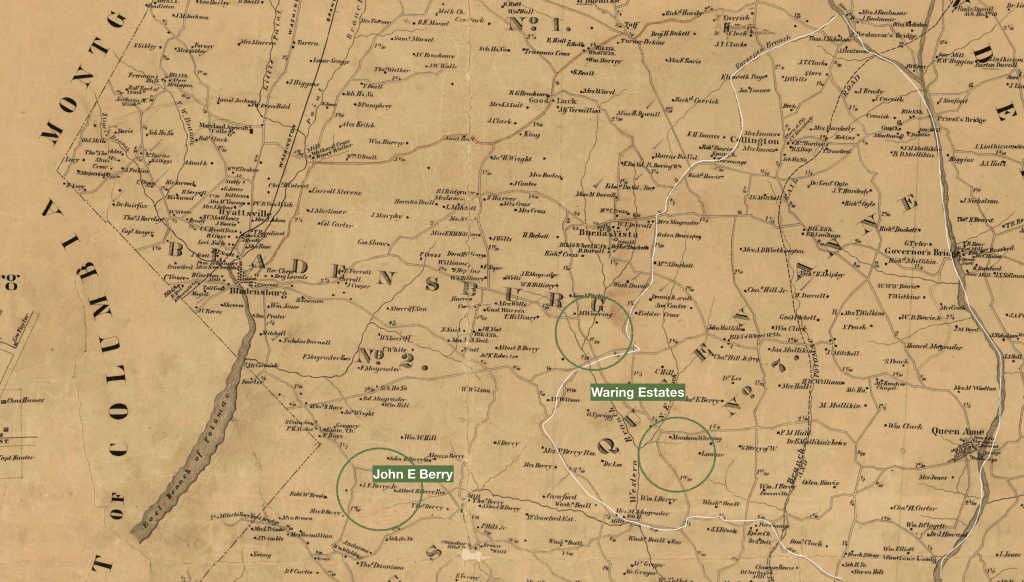

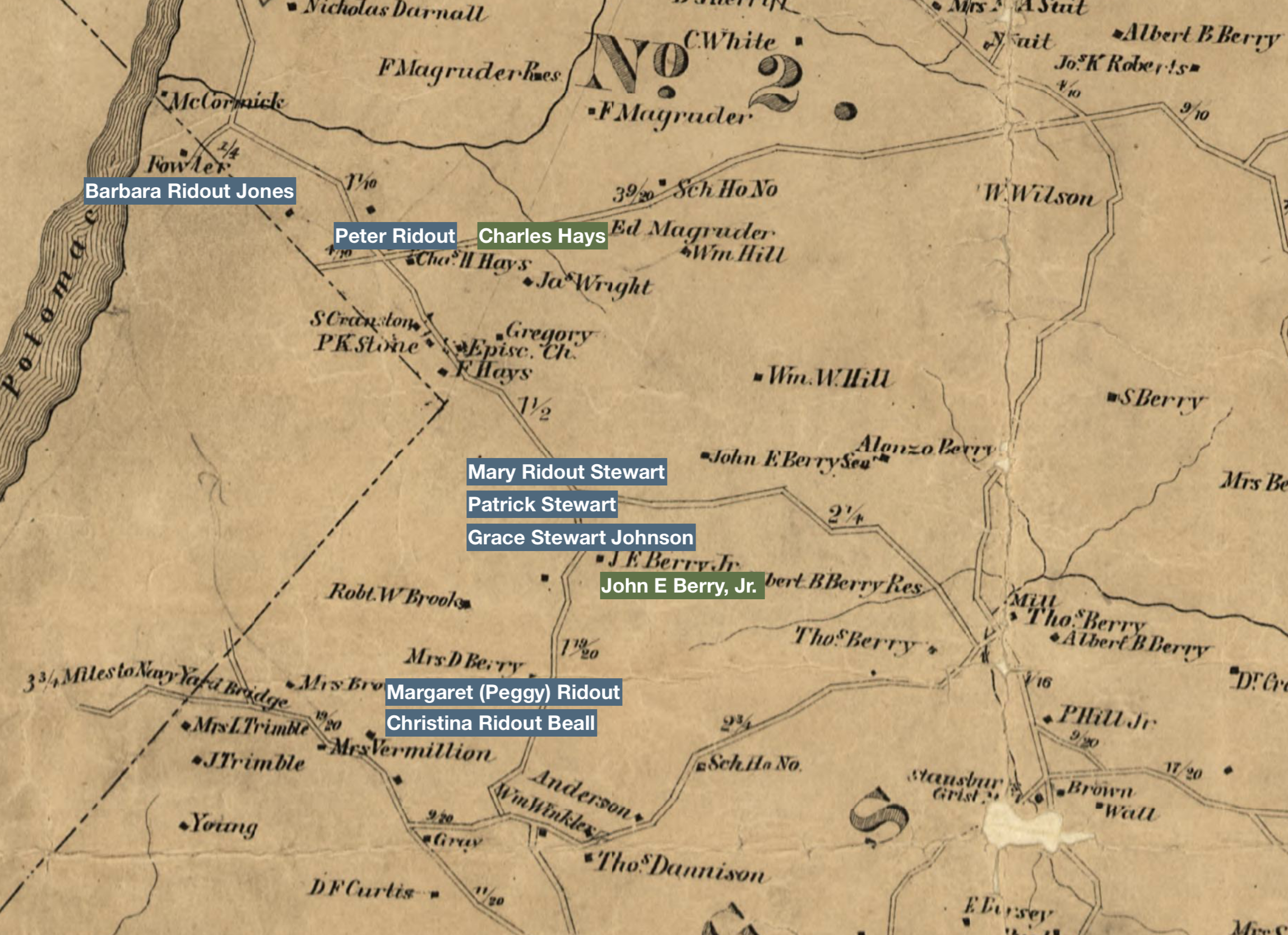

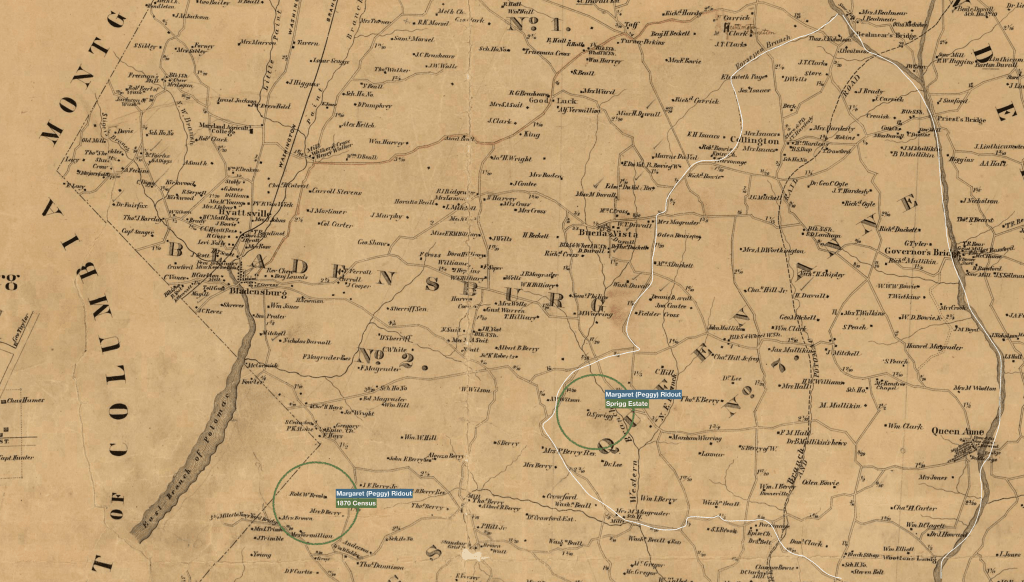

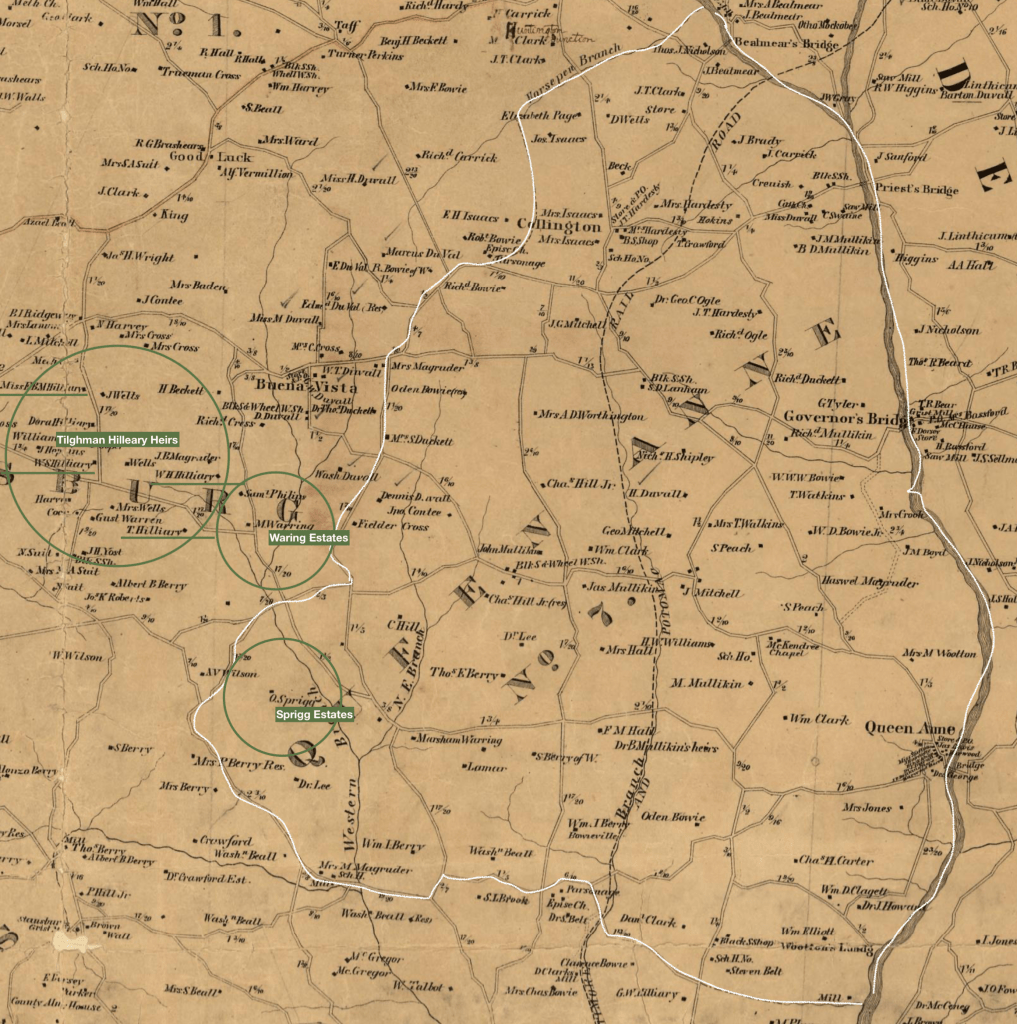

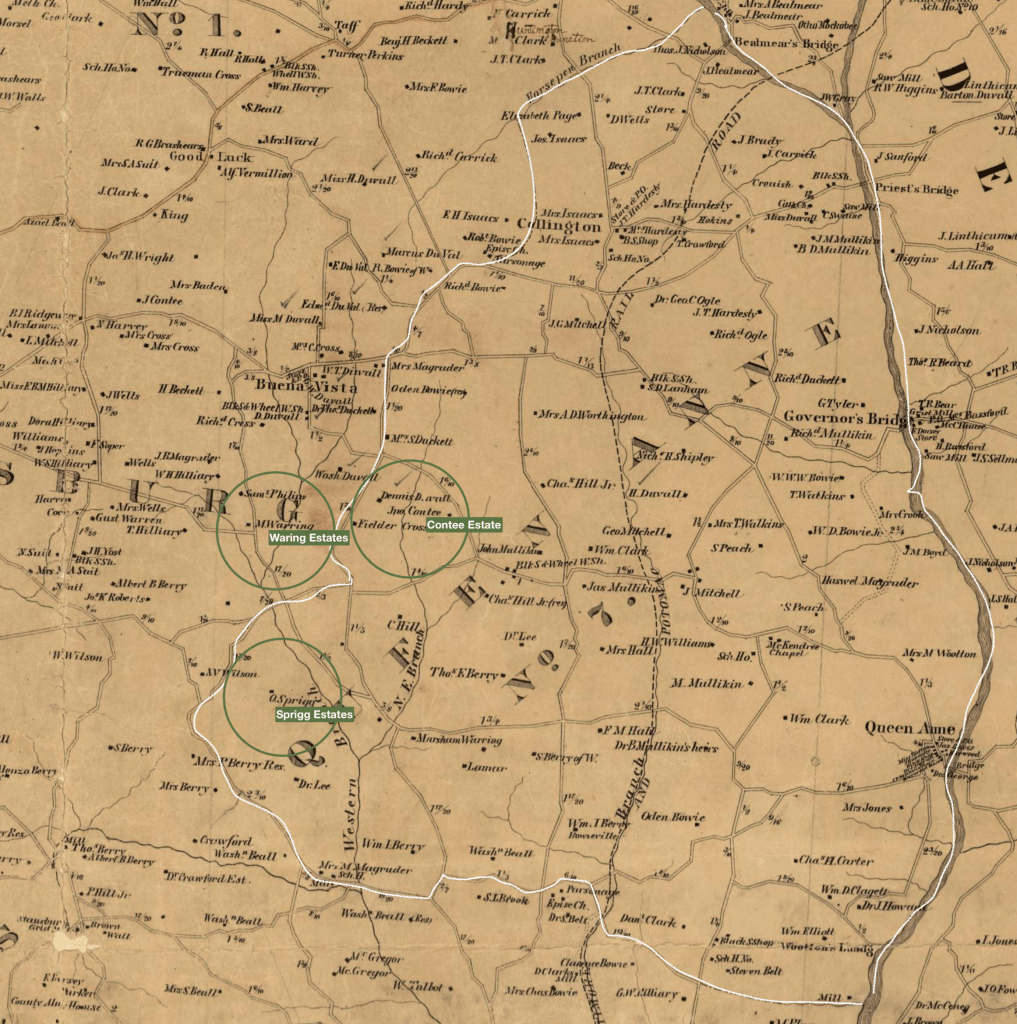

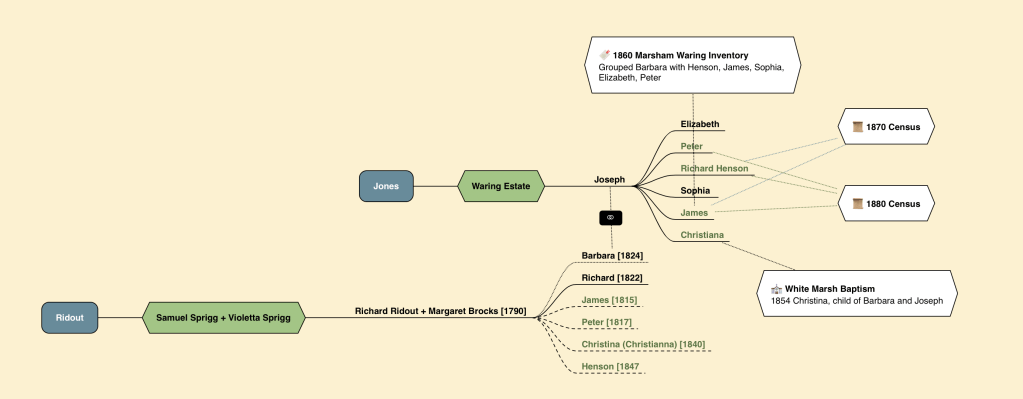

The court appointed James M. Boyd to act as trustee for Harwood’s accounts. Boyd was a landholder whose 160-acre farm, part of the tract “Ample Grange,” was situated about two miles north of Queen Anne Town. His property holdings, which included a tobacco house, corn house, granary, and “quarters for servants,” marked him as a successful small yeoman, a class of farmer holding between 40 and 280 acres. The scale of his diversified operation placed him at the upper end of this group, a man of sufficient standing and perceived stability to be entrusted by the court with the assets of a failed peer.

The legal process of insolvency, while offering relief from creditors, stripped Harwood of his economic autonomy and subjected his actions to the scrutiny of both the court and his community. The oath he swore—that he had not hidden assets to “delay or defraud his creditors”—would soon become a focal point of conflict. Within months, accusations would surface that directly challenged this sworn statement, moving the conflict from the formal setting of the courthouse to the arena of public opinion and vigilante action, where the planter network sought to enforce its own economic and social order.

the underground economy

an Economy within an economy: the m.s. plummer notice

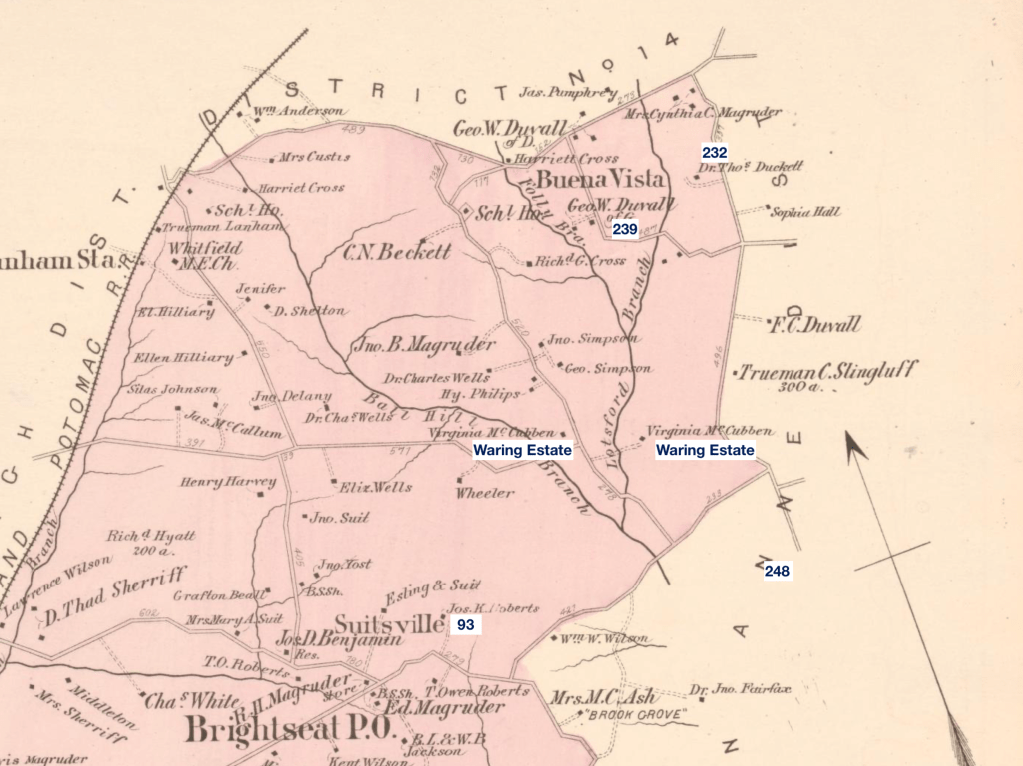

M. S. Plummer was a large planter whose estate on the border of Queen Anne and Marlboro District was home to the hundreds of people he enslaved. His real estate was valued at $120,000 and his personal property $500,000 in the 1860 census, speaking to his wealth acquired from the labor of the people enslaved on his estates. The heir of William Wells of George and married into the Waring family of Mt. Pleasant, M. S. Plummer was established among the large planter class.

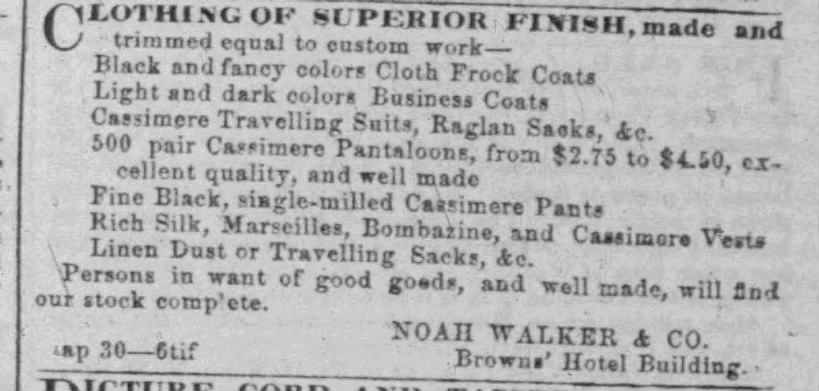

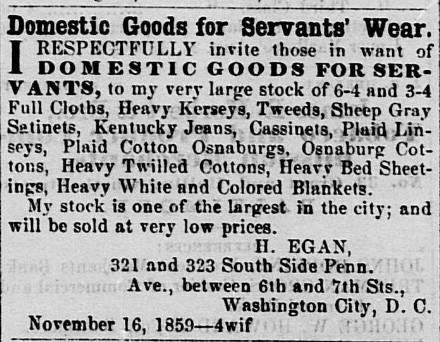

In July 1857, just months before the official start of a national financial panic, an unknown thief entered a cabin within the quarters on Plummer’s estate and stole clothing belonging to the enslaved occupants. The stolen items—including cassimere pants, a flowered vest, and lawn dresses—were not the rough, utilitarian workwear of tweed or osnaburg issued to field hands. Instead, they were fashionable, ready-made garments that, along with the five dollars also taken, point to the owners’ participation in the internal economy of the enslaved.

This underground economy was essential for survival and for carving out a space for self-expression. Through activities outside their forced labor, enslaved people generated income that allowed them to supplement the meager provisions provided by enslavers. They completed “overwork” tasks, sold produce from their garden plots, marketed handmade goods like baskets, and sometimes hired out their own time on Sundays or holidays. The resulting income enabled them to purchase goods from merchants or peddlers, trade for different foods, and acquire clothing that reflected their own tastes and style.

Transcription of Advertisement and Notice

$50 Reward.

I WILL give a reward of FIFTY DOLLARS for the apprehension and conviction of the rogue or rogues who entered one of my quarters on Thursday morning, the 9th instant, between ten and eleven o’clock, and took therefrom the following articles:

1 pair blue cassimere Pants, 1 black summer cloth Coat, 1 white Skirt, 1 white Vest with blue flower, 1 pair Shoes, with brass tacks, 1 blue lawn Dress, 1 pink lawn Dress. Also—Five Dollars in money.

And I also forewarn all free negroes, mulattos or slaves from Anne Arundel or Prince George’s Counties from crossing over or through my farm, either day or night, Sunday or any other time, without permission of myself or my overseers; and I will give TEN DOLLARS reward for the apprehension of every free negro or mulatto caught so trespassing.

I will give TWENTY DOLLARS reward for the conviction of any person or persons who deal with or purchase hogs, shoats, pigs, lambs, meal, fish or bacon from any of my servants, or who purchase such articles from others, stolen from my farm. And I will also give a liberal reward for any information that will lead to such conviction.

M. S. PLUMMER.

July 15, 1857—tf

Clothing Advertisements and Sketch of Enslaved People

Plummer’s notice sought more than the return of the stolen articles; it was a comprehensive effort to sever the networks that sustained the enslaved community. He issued a strict prohibition against Black people—enslaved or free—traversing his extensive estates, not only during the day but specifically at night and on Sundays, the very periods that allowed for a greater freedom of movement and social interaction. This clampdown on physical movement was directly linked to a more critical prohibition against economic exchange. By offering a reward for the conviction of anyone who purchased goods from his “servants,” Plummer attempted to dismantle the underground economy itself, denying the enslaved community the ability to profit from their own production and to exercise consumer choice.

opportunity knocks at the Quarters’ door

By publishing his notice in the Planters’ Advocate—a newspaper that served the interests of Prince George’s County’s white society with its advertisements for runaway enslaved people, trustee sales, and plantation managers—M.S. Plummer did more than just report a theft. He publicly drew a line against the local underground economy, threatening conviction for “any person or persons” who dared to purchase goods from the people he enslaved. This public ultimatum raises a critical question: who in the community would risk social condemnation and legal trouble by engaging in this forbidden trade? The circumstances of William B. Harwood, a merchant residing just a few miles away in Queen Anne Town, present a compelling answer. Declared insolvent just one month prior, his legitimate business shuttered and his assets seized by a trustee, Harwood possessed both the motive of financial desperation and the commercial skills of a merchant, making him an ideal candidate to operate within this illicit, cash-based market.

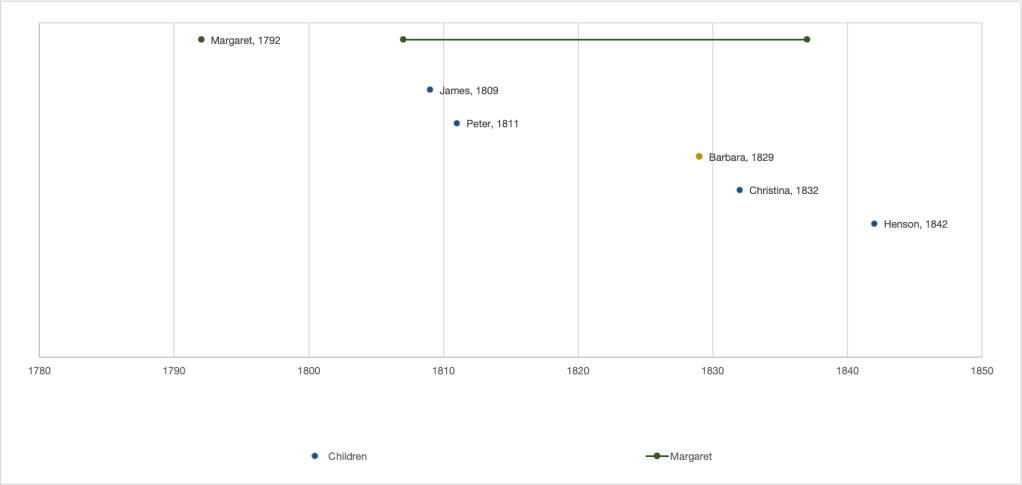

Although no single document provides direct evidence of William B. Harwood’s participation in the underground economy, a powerful case can be built from the convergence of his financial ruin and his social position. The 1850 census is a critical source, recording him not only as a merchant in Queen Anne but also as the head of a household that included the Coursey family, a free Black family. This long-standing association could have provided Harwood with a level of access and familiarity within the broader Black community—both free and enslaved. When his formal business collapsed in 1857, this pre-existing social network, combined with his skills as a merchant, would have made him an accessible and logical, if illicit, trading partner.

panic ignited

While Plummer was attempting to control the economic activities of the Black community, local enslavers were fearing the escape of their “valuable servants” through the Underground Railroad, often blaming “outside agitators.” Two attempts at self-emancipation from the summer of 1857 highlight this conflict between the enslavers’ public narrative and the reality of enslaved resistance.

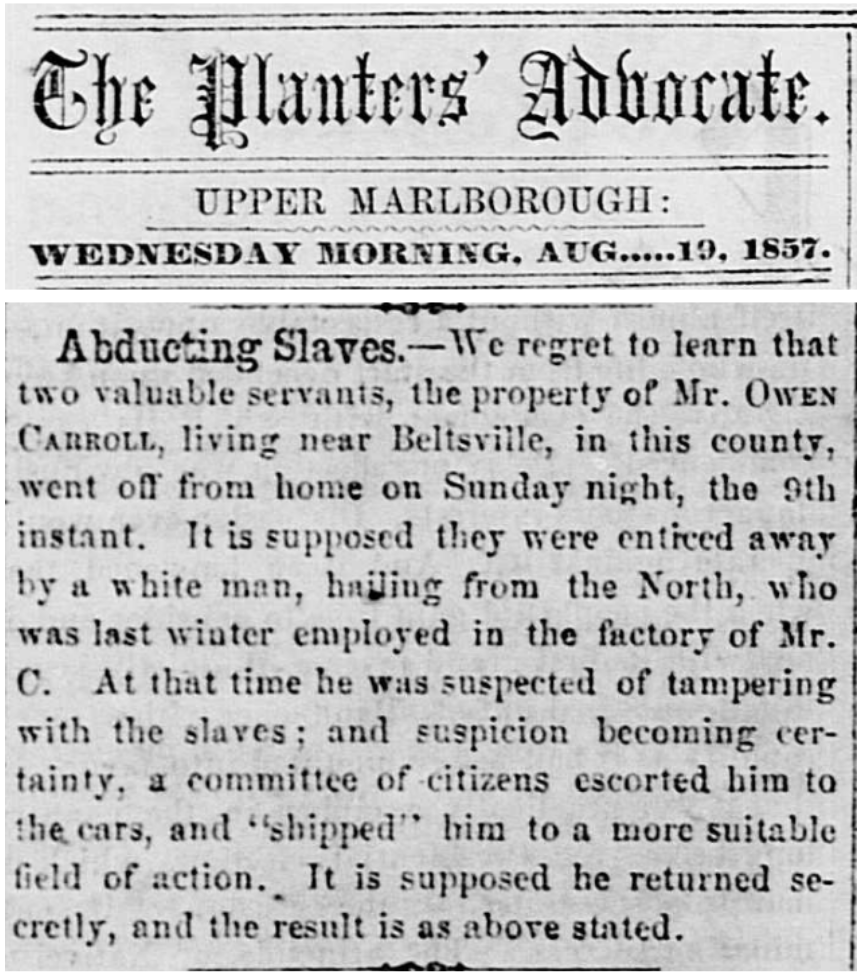

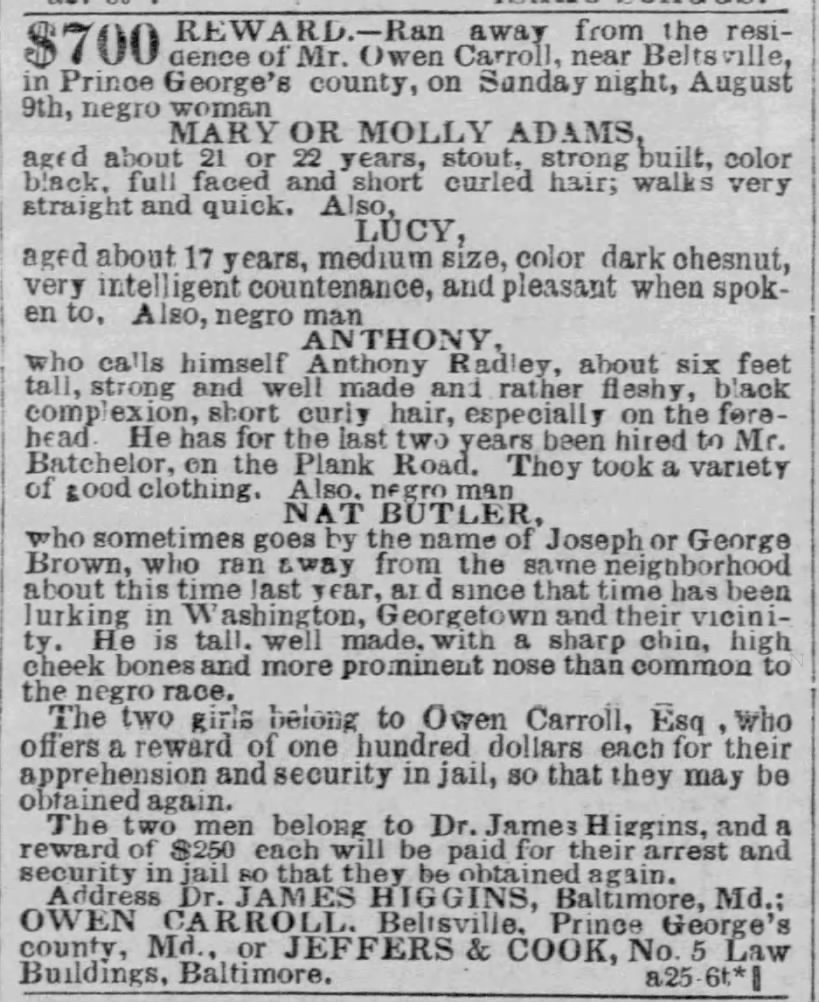

The first event was the coordinated escape of two enslaved women, Mary (Molly) Adams and Lucy, from Owen Carroll’s property, and two enslaved men, Anthony and Nat Butler, from a neighboring enslaver. The two news artifacts detailing this escape present conflicting stories. An article in the Planters’ Advocate frames the event as an abduction by a white Northerner, portraying the actions of a vigilante “committee of citizens” not as extra-legal intimidation but as a decorous civic procedure. This sanitized version stands in stark contrast to the reward notice placed by the enslavers. The bounty ad’s detailed descriptions of Lucy’s “intelligent countenance” and the men’s worldliness—Anthony having been hired out for years and Nat Butler being a prior runaway familiar with Washington and Georgetown—point to a group of capable, knowledgeable individuals. The joint escape of Mary, Lucy, Anthony, and Nat Butler suggests a carefully planned operation, undermining the paternalistic propaganda of the Planters’ Advocate, which sought to erase the agency of the self-liberating individuals by portraying them as guileless “servants.”

Transcription of “Abducting Slaves”

Abducting Slaves.—We regret to learn that two valuable servants, the property of Mr. OWEN CARROLL, living near Beltsville, in this county, went off from home on Sunday night, the 9th instant. It is supposed they were enticed away by a white man, hailing from the North, who was last winter employed in the factory of Mr. C. At that time he was suspected of tampering with the slaves; and suspicion becoming certainty, a committee of citizens escorted him to the cars, and “shipped” him to a more suitable field of action. It is supposed he returned secretly, and the result is as above stated.

Transcription of Bounty for Freedom Seekers

$700 REWARD.—Ran away from the residence of Mr. Owen Carroll, near Beltsville, in Prince George’s county, on Sunday night, August 9th, negro woman

MARY OR MOLLY ADAMS,

aged about 21 or 22 years, stout, strong built, color black, full faced and short curled hair; walks very straight and quick. Also,

LUCY,

aged about 17 years, medium size, color dark chesnut, very intelligent countenance, and pleasant when spoken to. Also, negro man

ANTHONY,

who calls himself Anthony Radley, about six feet tall, strong and well made and rather fleshy, black complexion, short curly hair, especially on the forehead. He has for the last two years been hired to Mr. Batchelor, on the Plank Road. They took a variety of good clothing. Also, negro man

NAT BUTLER,

who sometimes goes by the name of Joseph or George Brown, who ran away from the same neighborhood about this time last year, and since that time has been lurking in Washington, Georgetown and their vicinity. He is tall, well made, with a sharp chin, high cheek bones and more prominent nose than common to the negro race.

The two girls belong to Owen Carroll, Esq., who offers a reward of one hundred dollars each for their apprehension and security in jail, so that they may be obtained again.

The two men belong to Dr. James Higgins, and a reward of $250 each will be paid for their arrest and security in jail so that they be obtained again.

Address DR. JAMES HIGGINS, Baltimore, Md.; OWEN CARROLL, Beltsville, Prince George’s county, Md., or JEFFERS & COOK, No. 5 Law Buildings, Baltimore.

a25-6t*

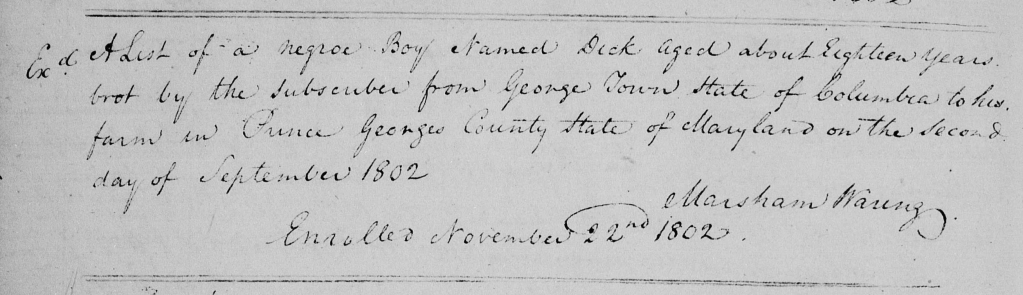

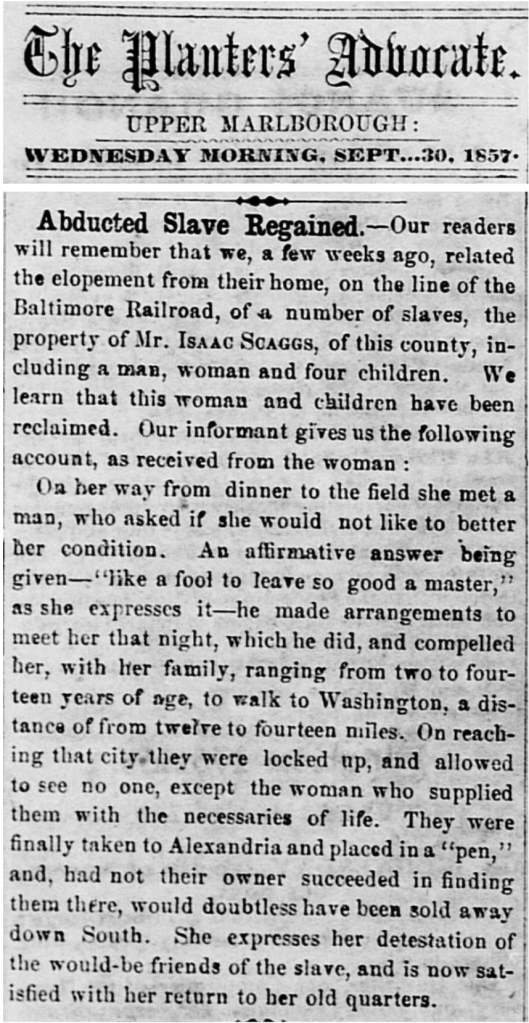

The second escape occurred in the same relative vicinity, involving a family from the farm of Isaac Scaggs. A series of articles and runaway ads describe the flight and subsequent recapture of Maria and her four children: Dall, Lem, Bill, and Ben. An initial report describes their escape as part of a larger “Stampede of Slaves,” noting the clear evidence of coordination as they acquired a wagon under the pretense of attending a camp meeting. Another article speculated they were seen on a canal boat near Cumberland, Maryland, suggesting they were using the C&O Canal to make their way north.

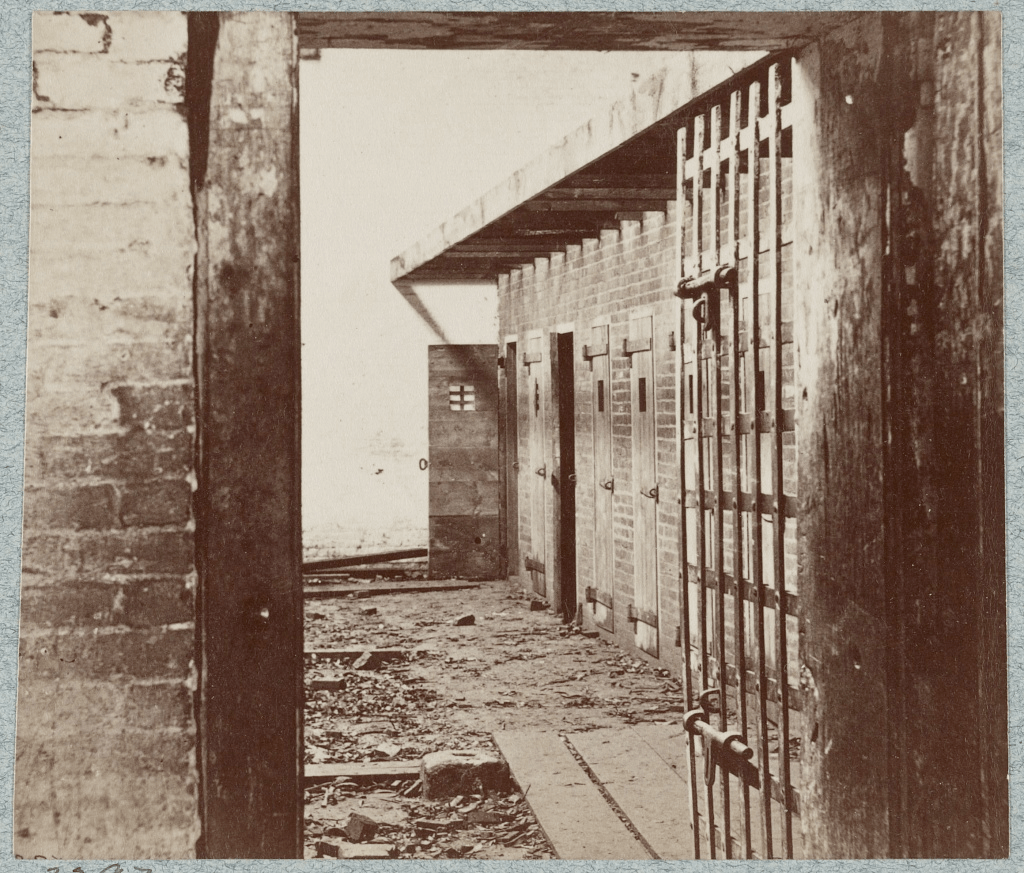

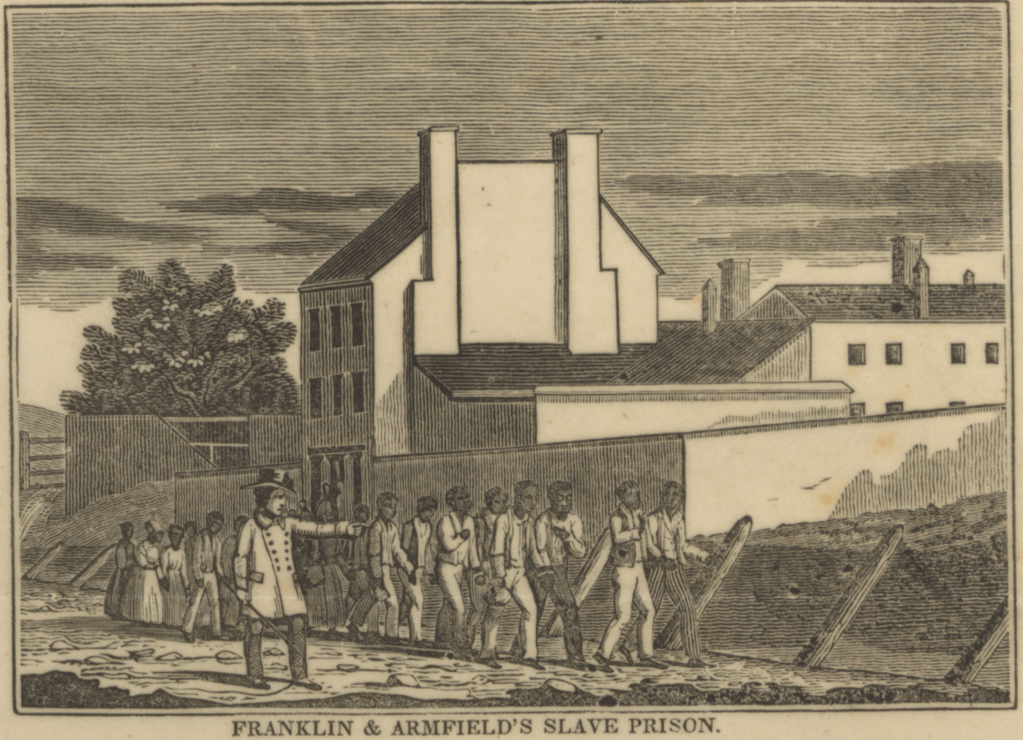

The bounty ads Scaggs placed, however, reveal a more intimate and courageous story. Adam Smith first self-liberated with the larger group, then risked his newfound freedom by returning to Scaggs’s farm to help his partner, Maria, and their four children escape with him. After the family was recaptured, Scaggs’s narrative shifted. He claimed in the press that a “would-be friend” had actually abducted them, intending to sell them into the domestic slave trade through a slave “pen” in Alexandria. This story, which contradicted earlier reports of an Underground Railroad escape, served to delegitimize abolitionist aid. As a final act of control, Scaggs had the newspapers publish Maria’s coerced “script of penitence.” Her forced expression of gratitude towards her enslaver was a calculated mode of survival, likely performed to ensure she and her children would not be sold South as punishment for their bid for freedom.

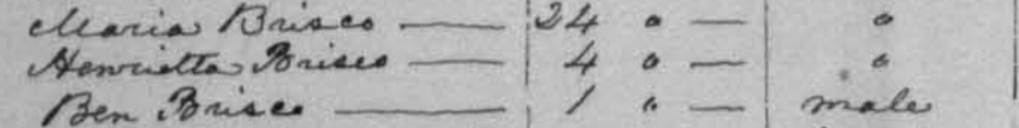

A post-emancipation record offers a final, telling chapter to the family’s story. In the Slave Statistics submitted by enslavers for potential compensation, Isaac Scaggs listed the people he held in bondage as of November 1, 1864, the date of Maryland’s emancipation. On that list were the four children: Dal (spelled Dall in the 1857 notice), Lem, Bill, and Ben.

Maria, their mother, was absent.

Her absence from the record points to one of two likely, and equally tragic, outcomes. It is possible that between 1857 and 1864, Maria made another, successful bid for freedom, a choice that would have required the devastating sacrifice of leaving her children behind. Alternatively, Scaggs may have made good on the implicit threat in the recapture notice, selling Maria to the domestic slave trade as a final act of retribution for her agency in the 1857 escape. Regardless of the specific path, the official record confirms the family unit was violently and permanently broken before emancipation arrived.

newspapers.com

Transcription of Stampede of Slaves

STAMPEDE OF SLAVES.—On Saturday, a number of slaves, belonging to various citizens of the District, obtained a covered wagon, under pretence of going to the camp meeting in the adjoining county. They departed, but have not returned, and their owners have reason to believe that they have emigrated by the underground railroad. Some fifteen slaves are missing, most of them belonging in this city and county. Among the losers are Messrs. Linton, Randolph, Harbaugh, and Isaac Scaggs. Officers have been in search of the fugitives, but up to this time none have been recovered.

Transcription of Abducted Slave Regained

Abducted Slave Regained.—Our readers will remember that we, a few weeks ago, related the elopement from their home, on the line of the Baltimore Railroad, of a number of slaves, the property of Mr. ISAAC SCAGGS, of this county, including a man, woman and four children. We learn that this woman and children have been reclaimed. Our informant gives us the following account, as received from the woman:

On her way from dinner to the field she met a man, who asked if she would not like to better her condition. An affirmative answer being given—“like a fool to leave so good a master,” as she expresses it—he made arrangements to meet her that night, which he did, and compelled her, with her family, ranging from two to fourteen years of age, to walk to Washington, a distance of from twelve to fourteen miles. On reaching that city they were locked up, and allowed to see no one, except the woman who supplied them with the necessaries of life. They were finally taken to Alexandria and placed in a “pen,” and, had not their owner succeeded in finding them there, would doubtless have been sold away down South. She expresses her detestation of the would-be friends of the slave, and is now satisfied with her return to her old quarters.

exorcism

illusion of Justice and Mercy

These events shook the established sense of security in Queen Anne District, creating a panic to rival the Panic of 1857. Not only was the global market in crisis, imperiling the sale of the planters’ cash crops, but Harwood’s insolvency was a stark reminder of the crisis that beheld the perilous role of credit in the lives of American capitalists. Moreover, agitators, decoys and the Underground Railroad was stealing the planters’ most valuable assets: the people they enslaved. This double threat to the financial security of planters required them to convene and establish a response to the threats to their security.

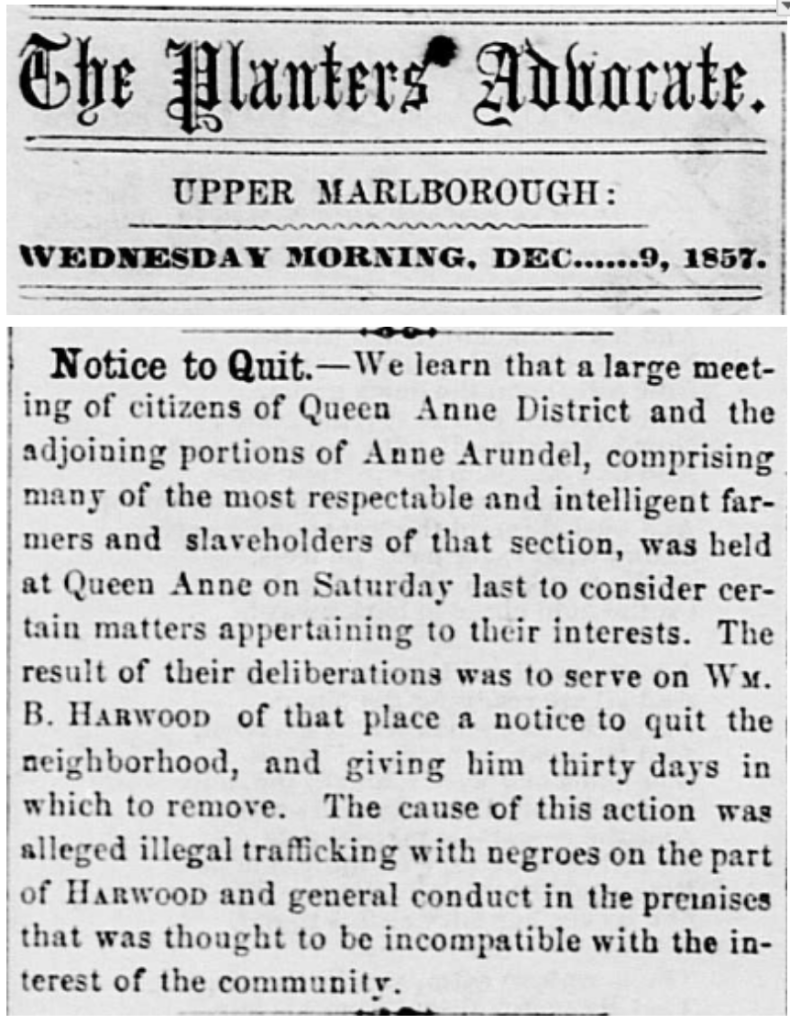

The planters of Queen Anne District, roiled by the recent events, met as a committee of citizens and as such, resolved that William B. Harwood, disgraced merchant, be expelled from Queen Anne for his “illegal trafficking with negroes” — the phrase “trafficking with negroes” could refer to the trafficking of stolen goods, warned about by M. S. Plummer, or could refer to the trafficking of stolen people, warned about by Isaac Scaggs. In either situation, the “most respectable and intelligent farmers and slaveholders of that section” acted outside of a legal court proceeding and as a self-appointed vigilance committee. By framing their meeting as a consideration of “matters appertaining to their interests,” they were asserting their collective power to define and enforce the social and economic rules of the community.

Occurring in the midst of a national financial panic and after a summer of high-profile escapes, the expulsion of William B. Harwood was the culmination of multiple crises. He was the perfect scapegoat: a failed merchant with a history of violating social norms. The “Notice to Quit” was the planter community’s definitive response, an act of vigilantism that purged a man they saw as a threat to their economic interests, their social order, and the institution of slavery itself.

Transcription of “Notice to Quit”

**Notice to Quit.—**We learn that a large meeting of citizens of Queen Anne District and the adjoining portions of Anne Arundel, comprising many of the most respectable and intelligent farmers and slaveholders of that section, was held at Queen Anne on Saturday last to consider certain matters appertaining to their interests. The result of their resolutions was to serve on WM. B. HARWOOD of that place a notice to quit the neighborhood, and giving him thirty days in which to remove. The cause of this action was alleged illegal trafficking with negroes on the part of HARWOOD and general conduct in the premises that was thought to be incompatible with the interest of the community.