Connected Post: Richard (Dick) Jones & Mary (Polly) Jones | Old Age

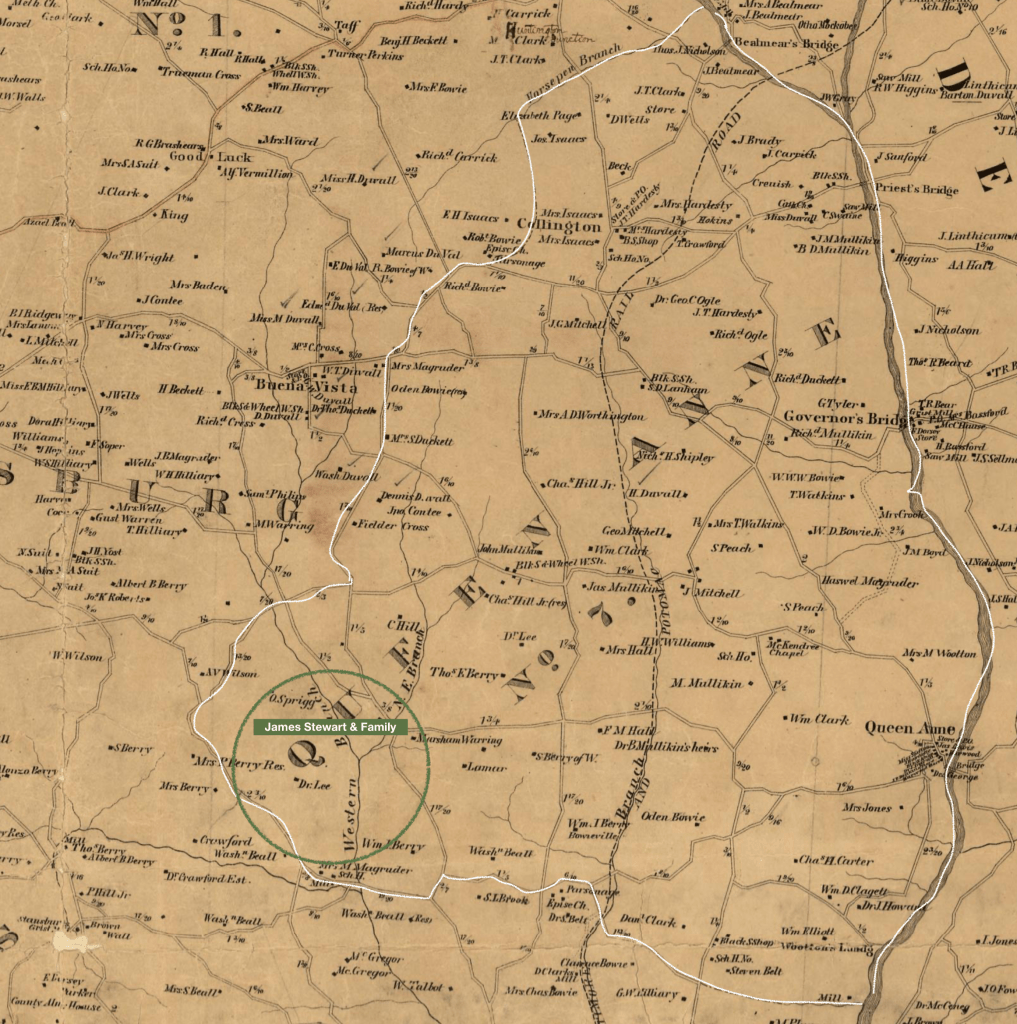

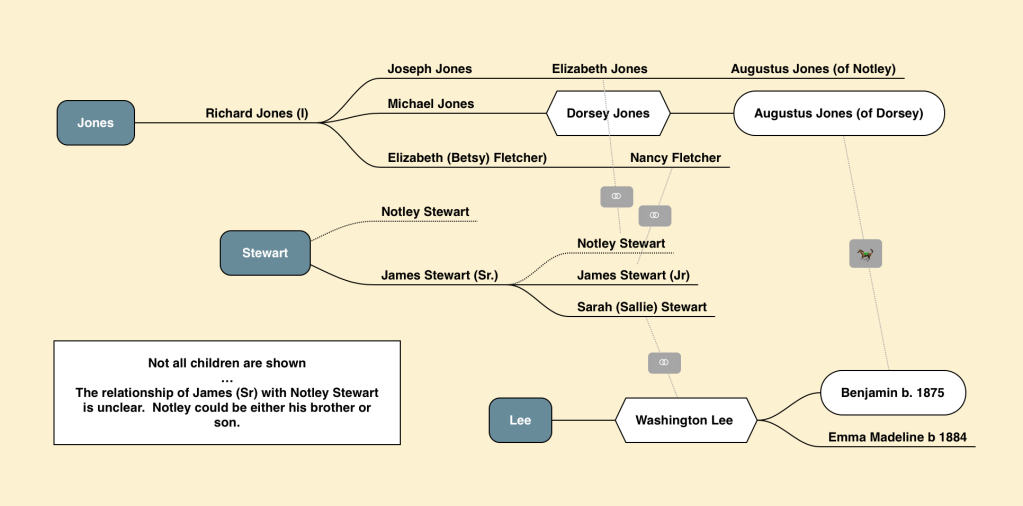

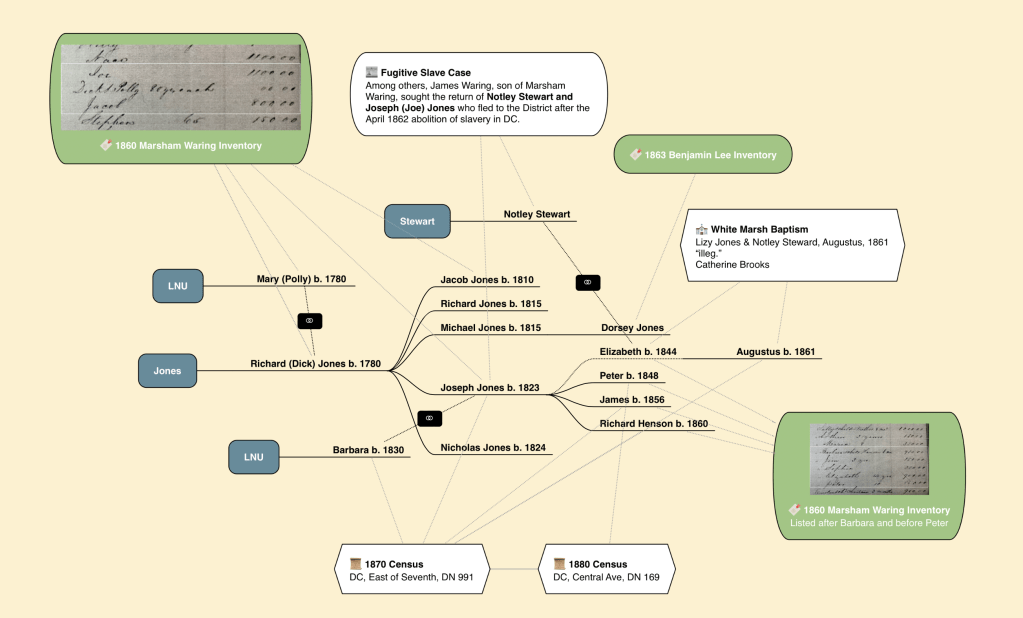

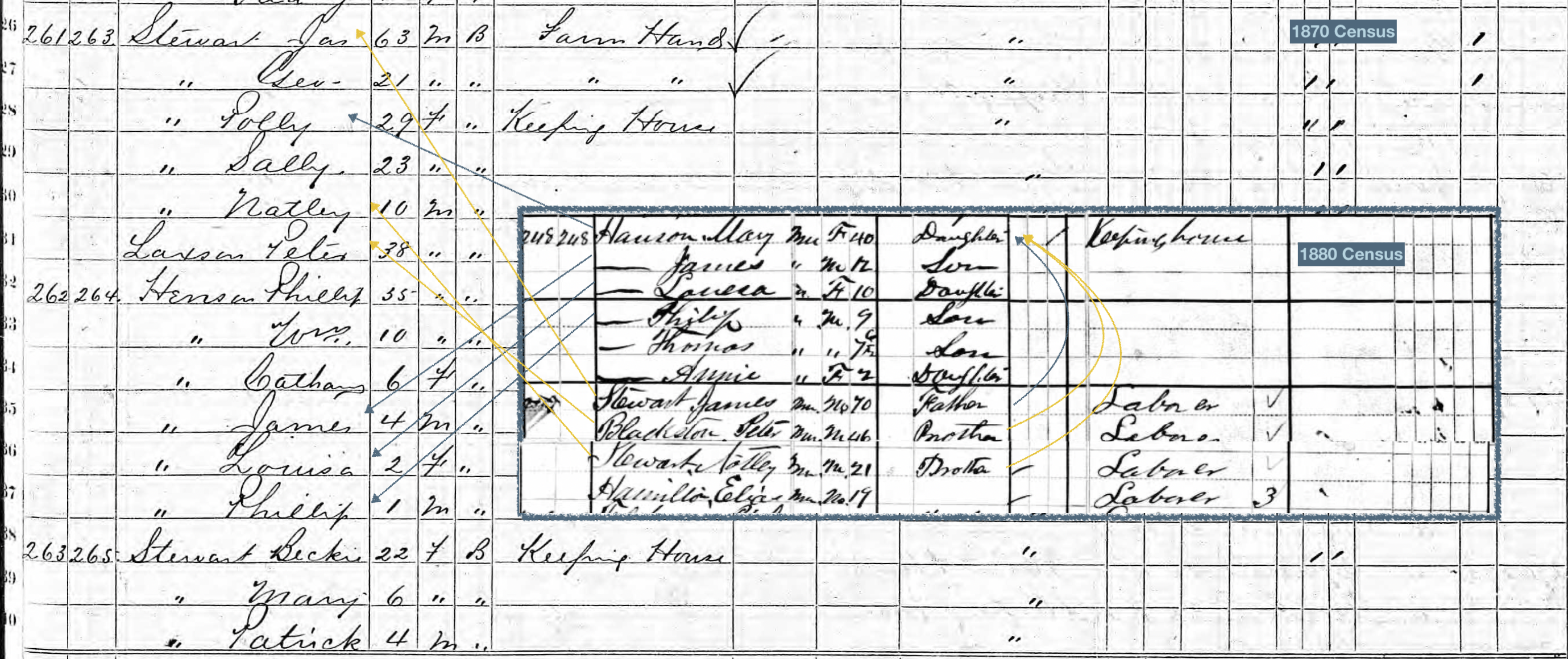

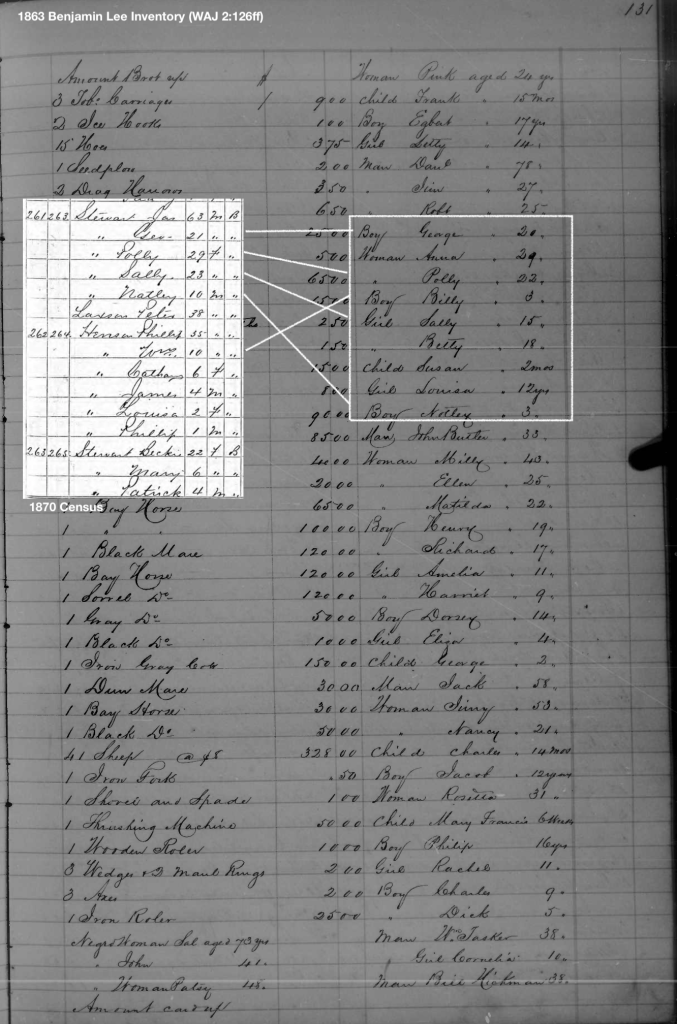

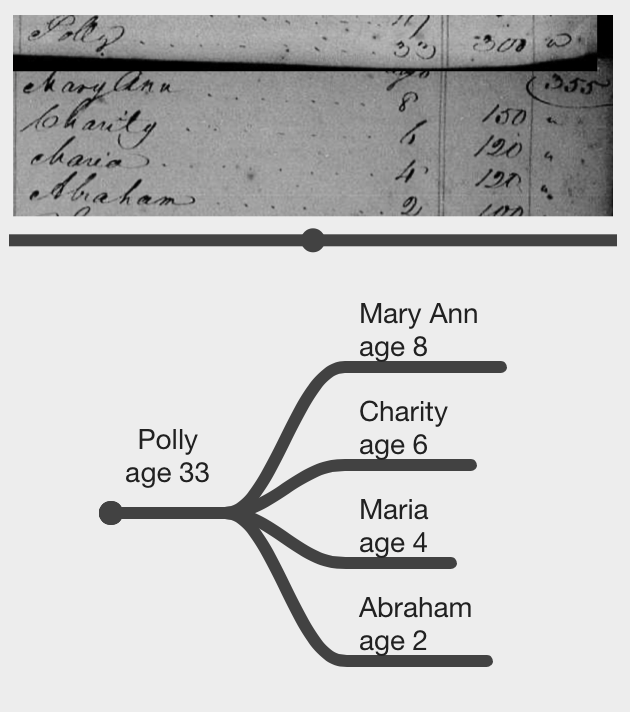

Richard (Dick) Jones and his wife, Mary (Polly) were born at the end of the Revolutionary War and lived until the start of the Civil War in Queen Anne District of Prince George’s County. The vast majority of their life was spent on the estates of Marsham Waring. They and their children labored for Waring and his three children, as well as neighboring estates. This post explores the life of one of their sons, Joseph Jones.

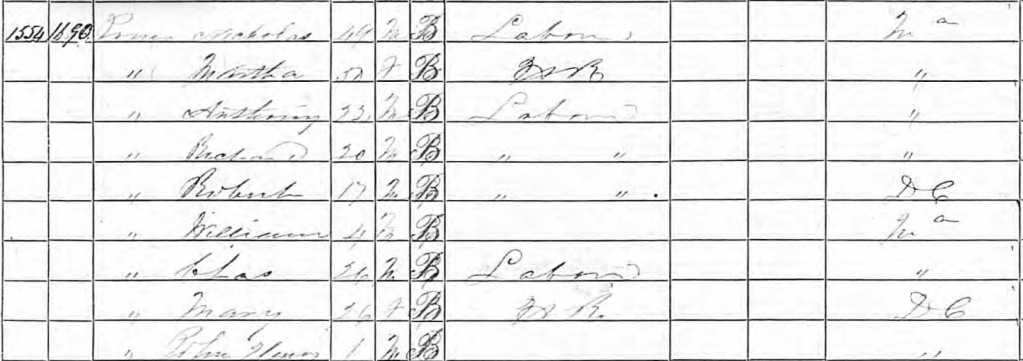

Joseph Jones was one of Mary’s younger sons. He labored on Warington, which was the main dwelling estate for the Warings, along with his parents, wife and children

Joseph and Barbara had three of their children’s baptisms recorded by the priests of White Marsh.

- “Johns, Christina, daughter of Jos. Johns & Barbara Reyder, his wife, born May 3, 1854, property of Mr. Marsh. Waring. Godmother: Susana Steward.”

- “Do: James, 2 weeks old, of Joseph & Barbara, property of M. Waring. Sp: Selley.” [1857]

- “Bapt’. Richard of Joe & Barbara Jones, col’, 10 weeks old. Spons: Bettzy Fletcher for Martha Colbert.” [1860]

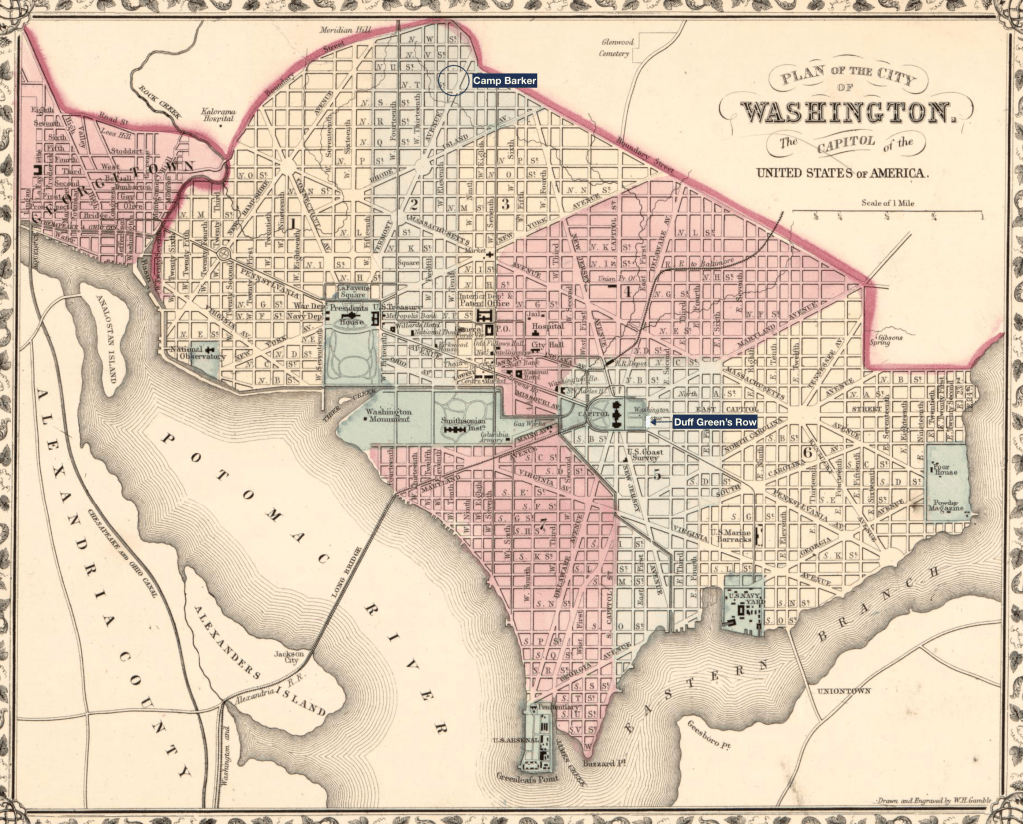

In May 1862, a group of enslaved people from Waring’s estates fled to DC with James Waring, Marsham’s son, pursuing them. He swore out an affidavit, swearing that they were enslaved in Maryland, not the District, and therefore he was lawfully able to seek their return to bondage. Joseph Jones was among those named by Waring.

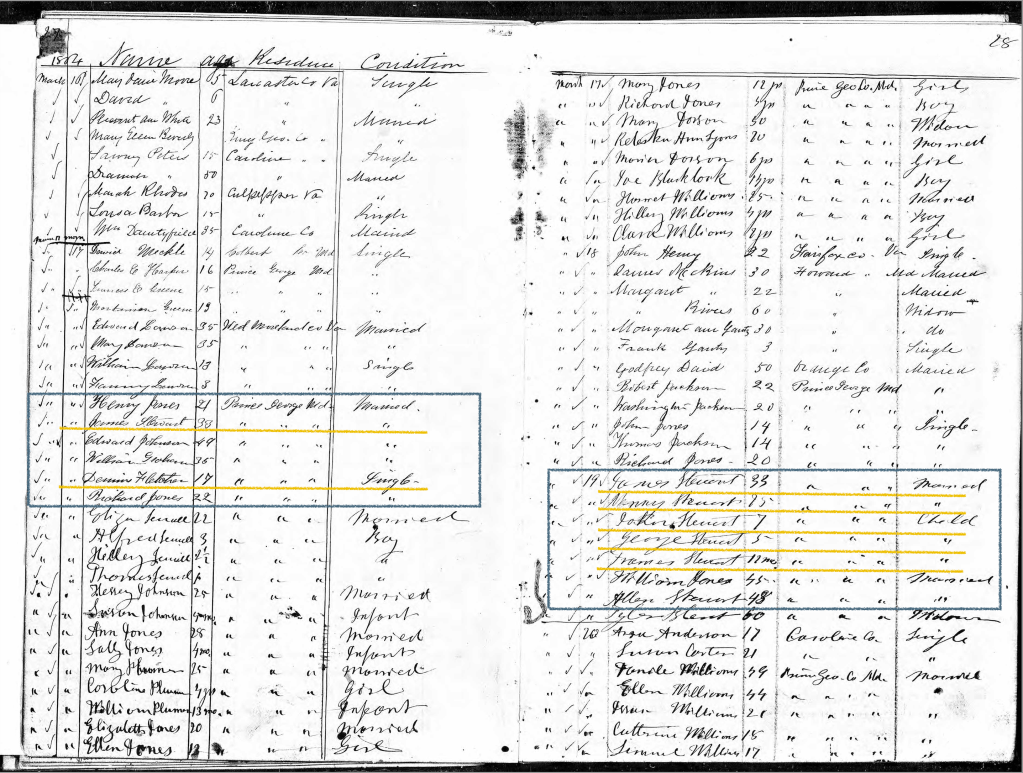

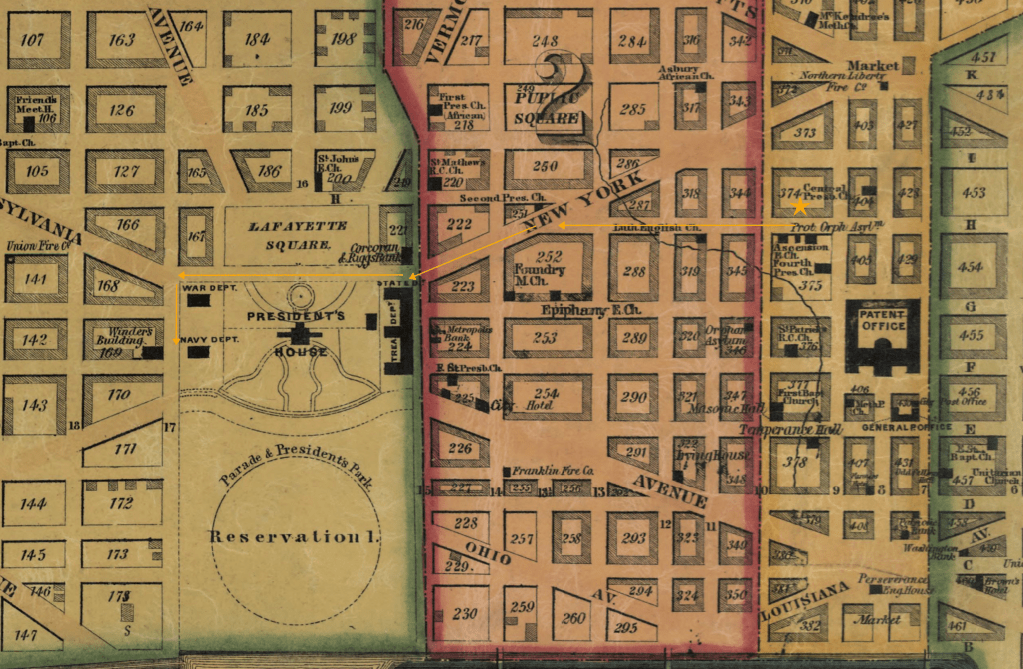

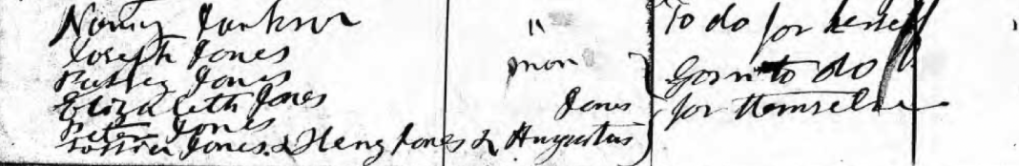

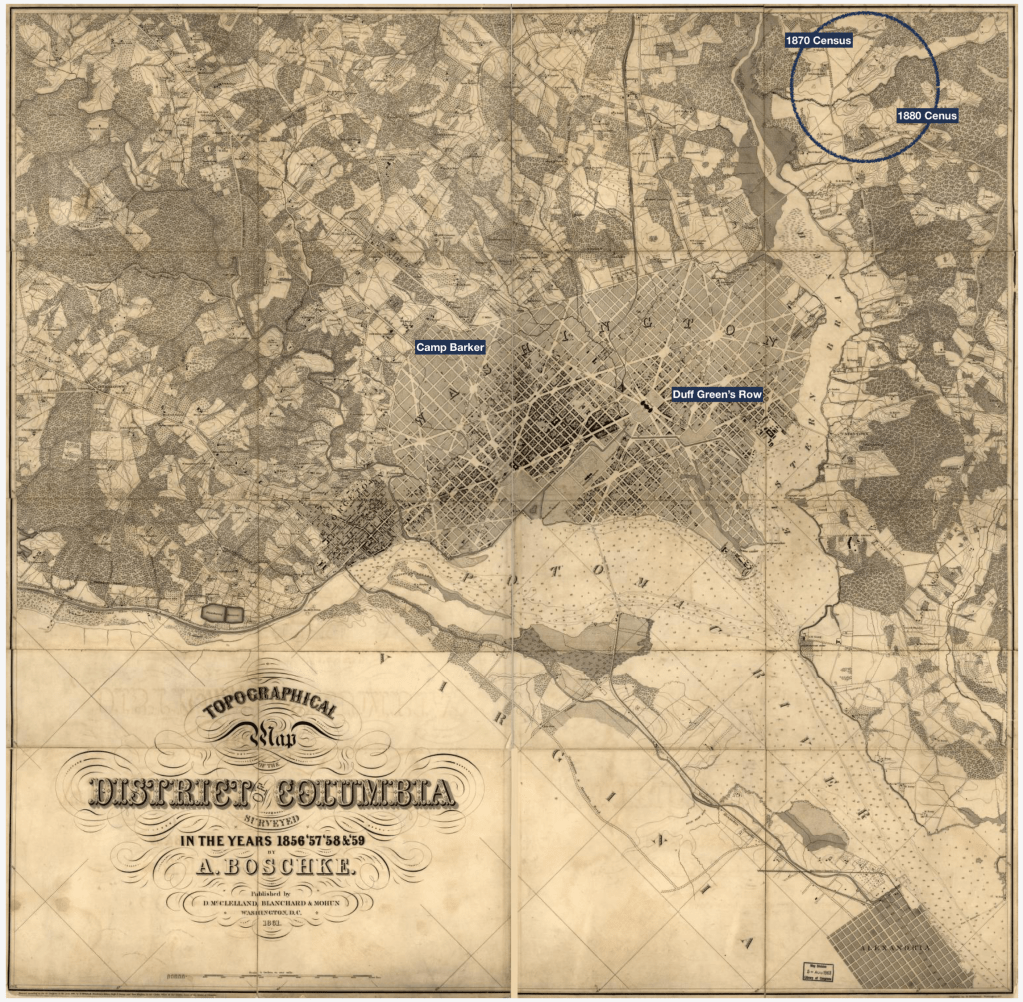

Joseph and his wife, Barbara, and their children are listed on a registration list for Camp Barker, a refugee camp set up in the northern part of the City of Washington, near U street and Vermont Avenue.

U.S., Freedmen’s Bureau Records, 1865-1878 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2021. | ancestry.com

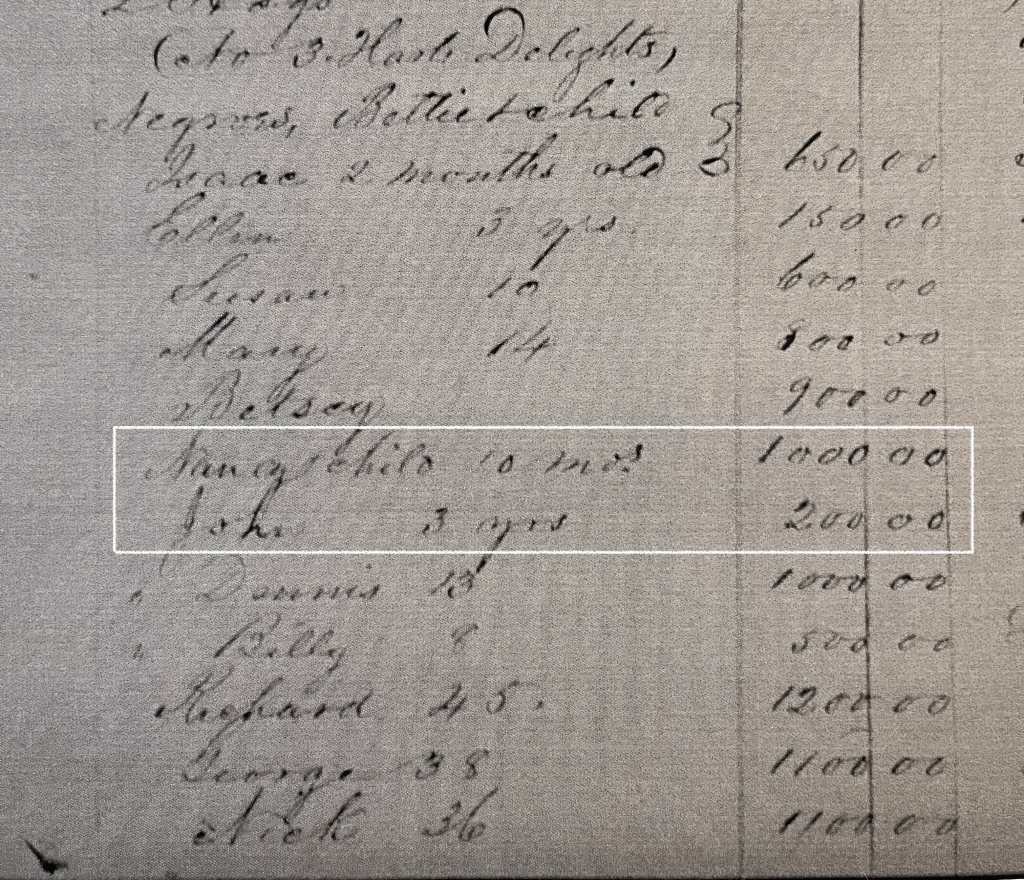

Marsham Inventory WAJ 2:321 | Maryland State Archives

“The present shelter of the refugees in Washington is called Camp Barker. We visited it on the 25th of 11th month. It consists of a large oblong square, surrounded on three sides by huts or barracks, and other buildings, all opening within the square; and by a high fence on the west side. The entrance is under a military guard. The huts, about forty-eight in number, are about twelve feet square, and each have from ten to twelve inmates. There are also several large tents, occupied by old or infirm men, and two buildings called hospitals—one for men, and one for women. The residence of the superintendent is within the enclosure.”

Report of a Committee of Representatives of New York Yearly Meeting of Friends upon the condition and wants of the colored refugees. | loc.gov

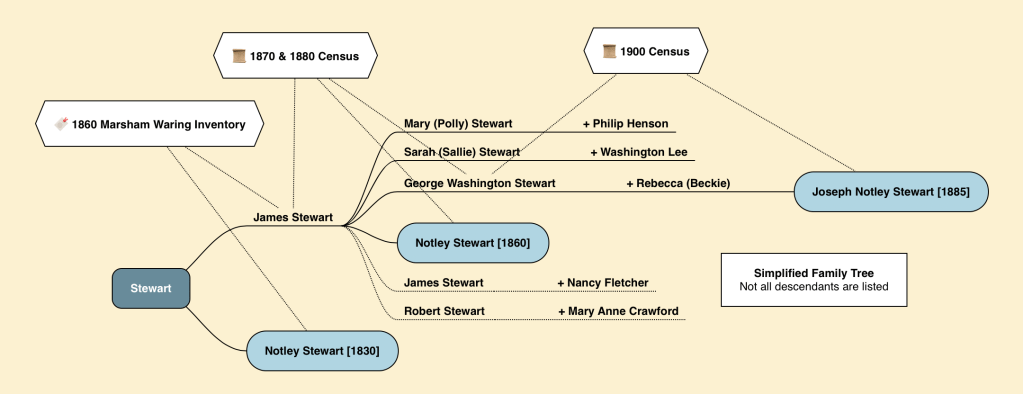

In 1861, the baptism for Augustus, the son of Lizy Jones and Notley Steward was recorded. Augustus is in the registration list for Camp Barker with Joe, Barbara [Patsy] and Elizabeth. Notley Stewart, with Joseph Jones, was listed on the affidavit by James Waring. Notley is not listed with the Jones family, though Elizabeth and Augustus are listed together.

At some point, they may have been transferred from Camp Barker to Camp Springdale, which was the precursor to Freedmen’s Village on the Arlington Estate (owned by Robert E Lee’s wife) and what would become Arlington Cemetery. They appear on a list of those who left Camp Springdale. The note indicates that they “gone to do for themselves”

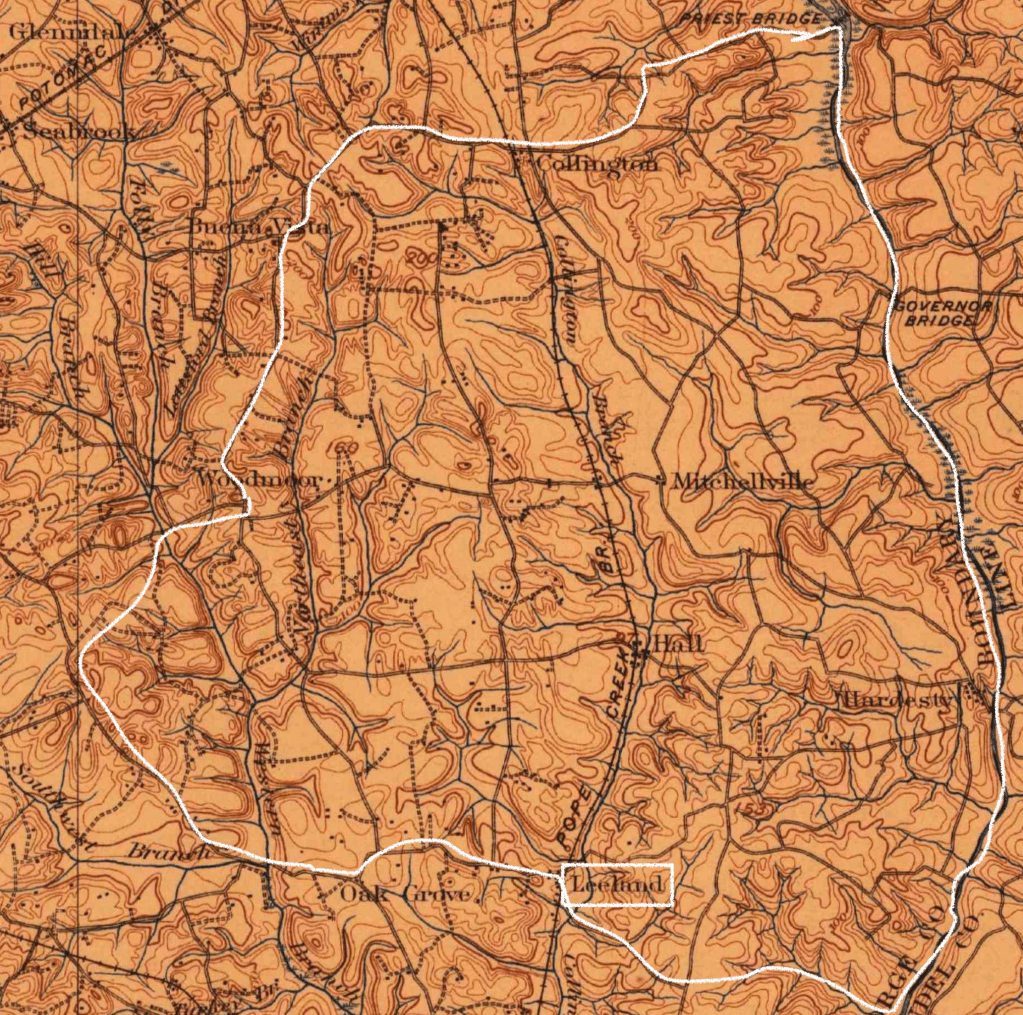

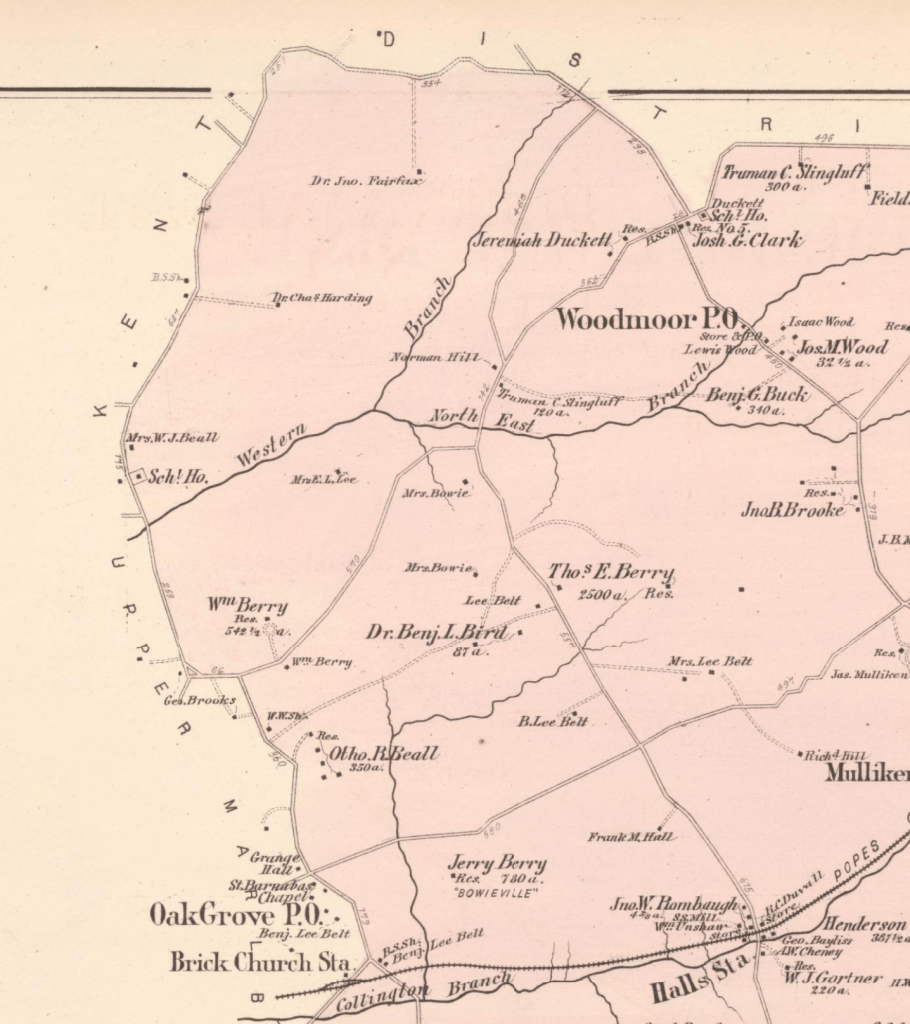

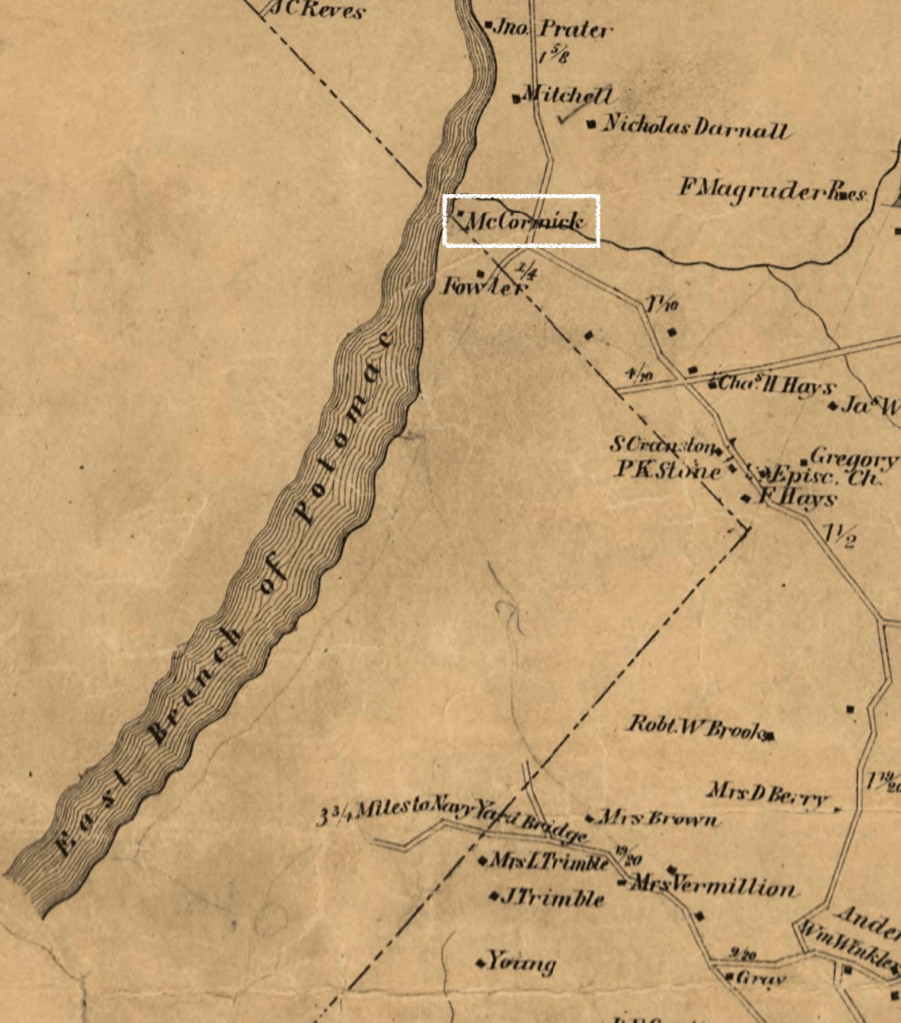

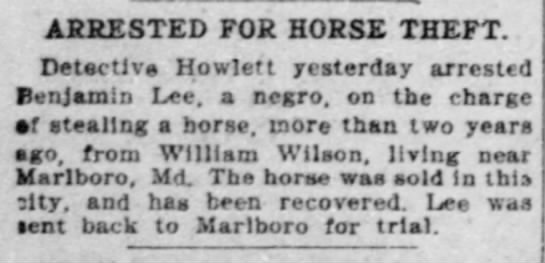

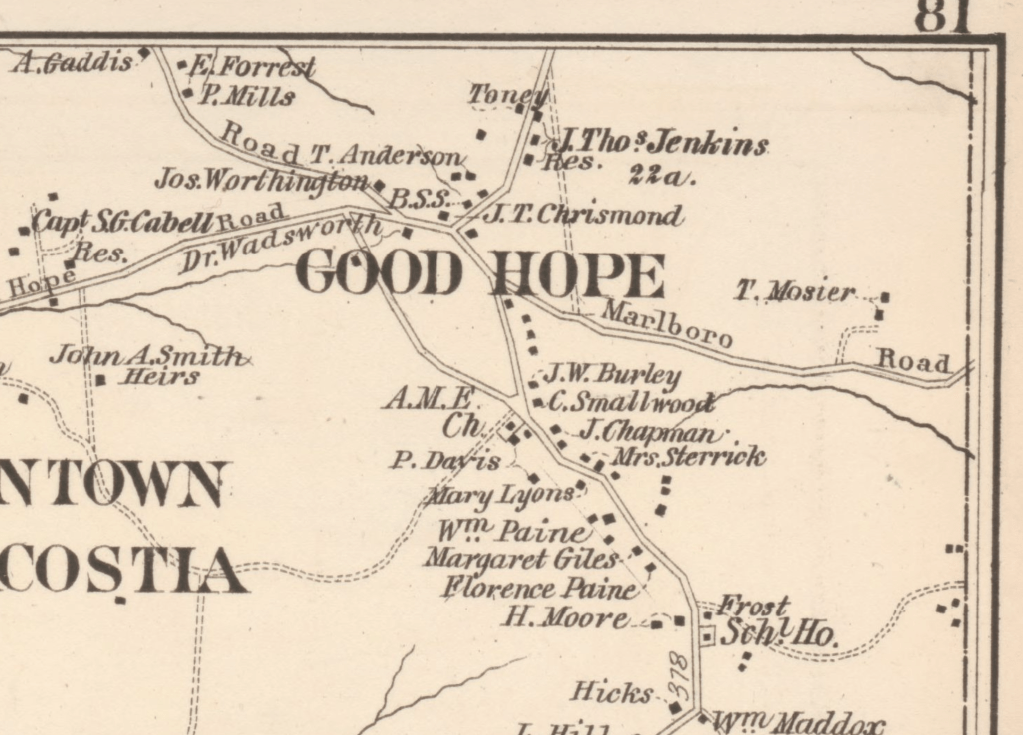

After the war, Joseph and his family settle outside the City of Washington in the District in and around Benning’s Road. In 1870, they lived near Alex McCormick along the Maryland-District Border. McCormick had used his location along the border to hide the people he enslaved in Maryland when the District abolished slavery. The family successfully petitioned for their freedom. See Civil War DC for more information about this petition. Living with McCormick in 1870 is Robert Jones, a nephew of Joseph Jones. Of their children, Sophia and Peter are not listed with them in 1870. Peter rejoins them in 1880, but not Sophia. This suggests the likelihood she died, though it is possible she married.

It’s likely that Barbara died in 1896; a death record for a Barbara Jones, born around 1824 in Maryland can be found. She was buried in Mt. Olivet, a Catholic cemetery. No family members are listed.

Her son, Peter Jones, is still living in the vicinity of Benning’s Road in the 1900 Census. He is working in a stock yard, and his son, Peter Jones, Jr. is working as a jockey.