In a previous post, we explored the children of Susan Wood, who married Charles Brown, both of whom were listed in the 1853 Inventory of Robert Darnall Sewall. One of Susan’s children was named Dinah. She was likely named after Susan Wood’s grandmother, Dina.

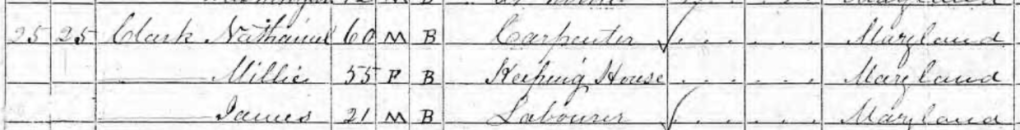

Dina in 1821

Dina, age 66, is listed in the 1821 inventory of Robert Sewall. She would have been born in 1755. She is listed with two adult males, Abraham, 38, and Jack, 19. Their relationship to Dina is unclear.

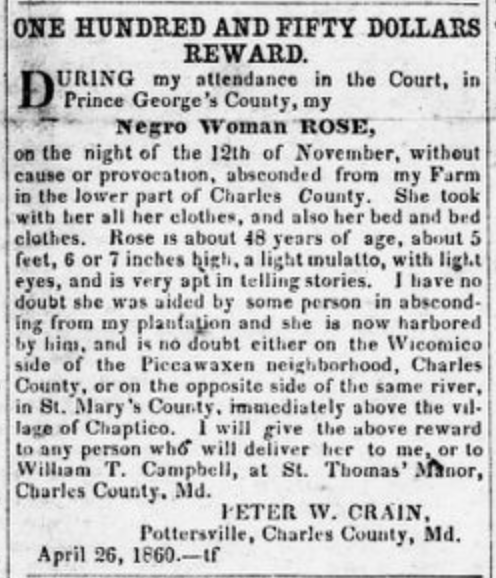

Dina before the Sewalls

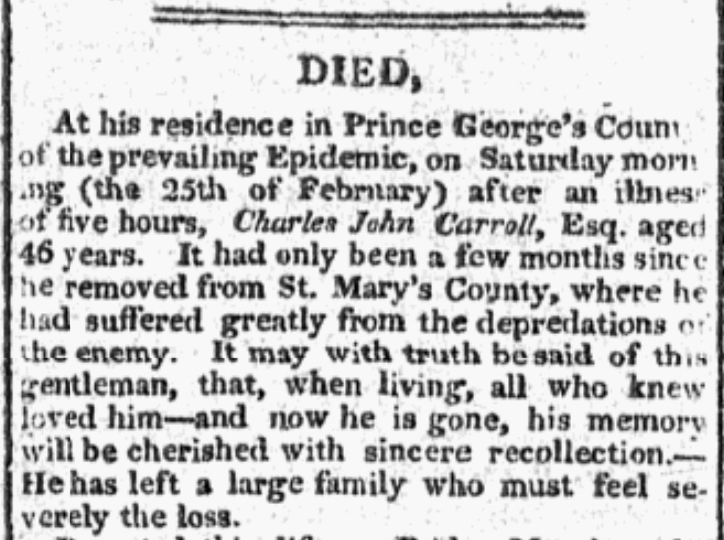

Robert Sewall inherited the legal authority to enslave Dina and her offspring when Robert Darnall died in 1803. Prior to that Dina had been in the possession of Robert Darnall and his step-daughter, Jane Fishwick.

Prior to reacquiring “Poplar Hill” in 1773, Robert Darnall had lived in Dorchester County across the Chesapeake Bay, with his wife, the wealthy widow, Sarah Fishwick. When he was able to buy back “Poplar Hill”, Darnall brought his wife and his step-daughter from Dorchester County to Prince George’s County.

When the Darnalls moved, Jane Fishwick brought her personal “servant” with her, separating Dina from kin in Dorchester and bringing her to work in the Darnall household.

While in Prince George’s County, Jane fell ill and died in 1775. Her illness required medical care, which Darnall was not prepared to pay without being recompensed out of Fishwick’s estate. As a result, he claimed Dinah and her children as his chattel property.

Decades after Fishwick’s death, other kin laid claim to Dina and her children, saying that Darnall had illegally taking possession of her and her subsequent children.

The ensuing legal case, “Fenwick v Sewall” [1818], named Dinah and her children and grandchildren, which when compared against the 1821 Sewall Inventory [TT 4:352], provides additional connections between family members. Those named include: Fanny, Phillis, John, Paul, Moses, Susannah, Pat, Isaac, Charles, Nelly, Sally, John, Sampson, Tom, Nancy, Kit, Anna, Harriott. [p. 397]

“Dinah had seven children, to wit, Fanny, Patt, &c named in the declaration all of whom were living, and were born after the death of the plaintiff’s intestate:

- John &c are the children of Fanny

- Isaac, Nancy &c are the children of Patt and

- Harriott is the daughter of Nancy who is deceased and who is the daughter of Dinah.”

[Bulleting mine]

In the dispositions, Dinah was said to have been the mother of seven children and ten grandchildren. In a later case, an additional claim was made as Sal, Pat, and Phyllis [1821] had a child in the interim.

Many of these names correspond to the names included in the 1821 Inventory of Robert Sewall [TT 4:352], the heir of Robert Darnall who is alleged to have taken unlawful possession of Dinah and her offspring after Fishwick’s death.

Dina

| Inventory Line Number | Name | Age | Est BY | Notes |

| 81 | Dina | 66 | 1755 | There are two women named Dinah enumerated (age 66 and 37) in the inventory. If Dinah was old enough to be a mother and grandmother of 17 people in 1818, as well as seen by Dr. Digges in 1775 with a nursing child, then this excludes the younger Dina whose estimated birth year of 1784 makes her too young. And assumes the older Dina who would have an estimated birth year of 1755. Dina is listed with Abraham, age 38, and Jack, age 19; neither are listed in the court case. |

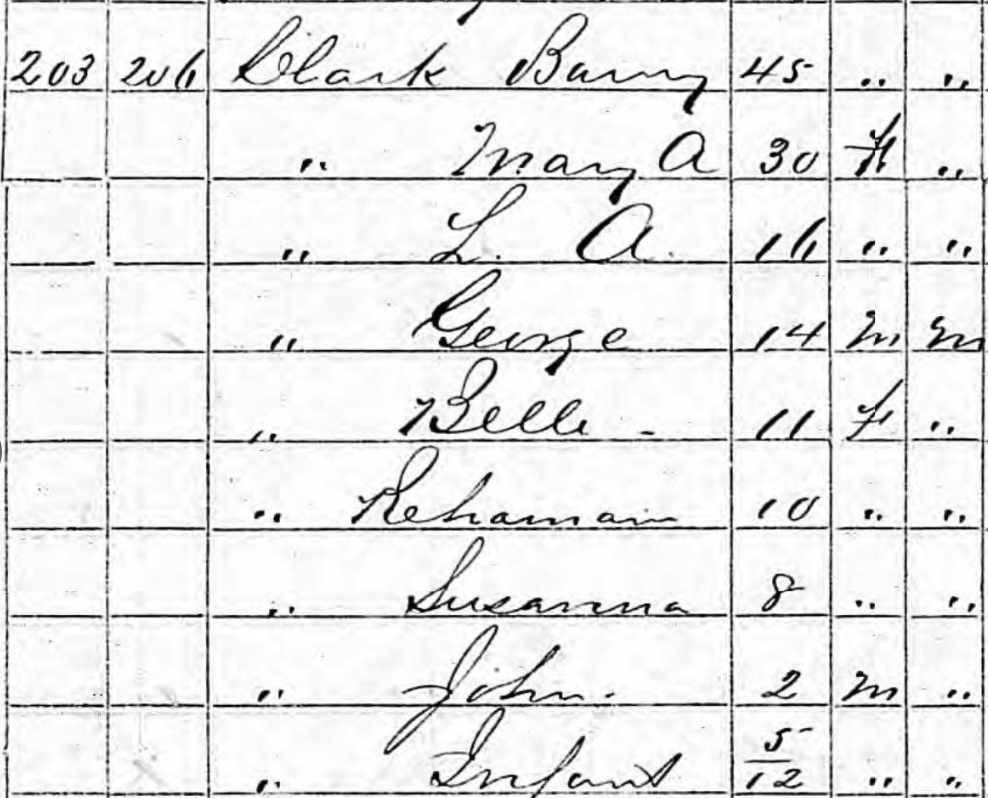

Fan & children (1 child + 4 grandchildren) [Wood]

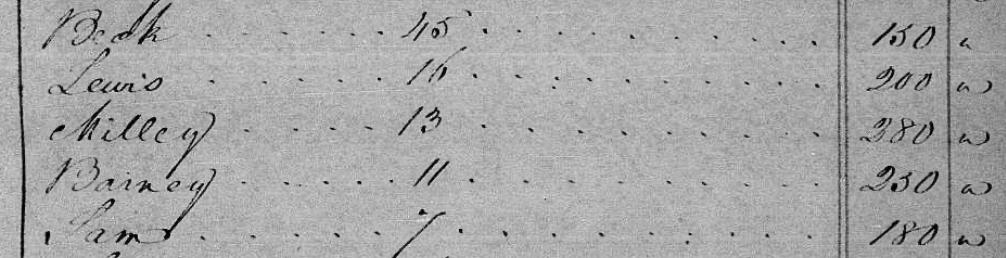

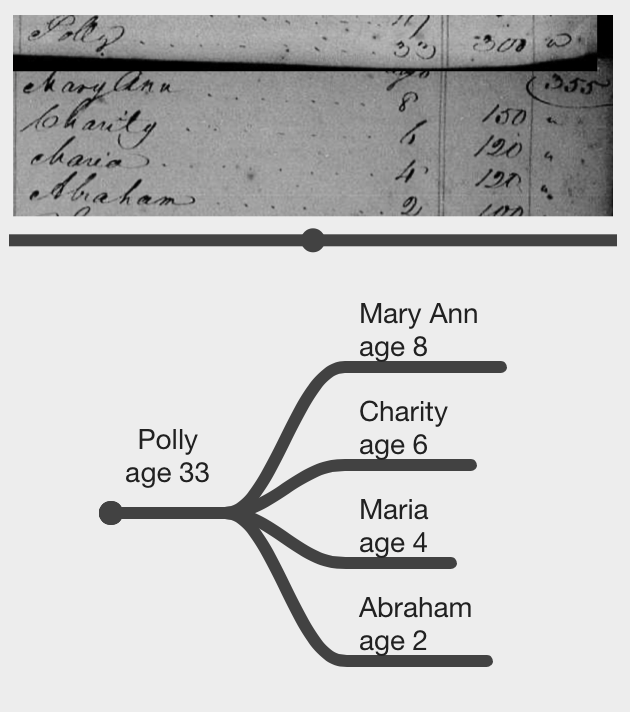

In the 1821 Inventory of Robert Sewall, the following family group is recorded:

Fan is listed with her four children, John, Paul, Suck, and Moses, and her daughter-in-law Phillis and her two grandchildren, Eliza and Kitty.

Previous posts have talked about the children as individuals, and their children as identified in the 1870 census. [John Wood, Eliza Wood, William Hannibal Brown Gantt].

| Inventory Line Number | Name | Age | Est BY | Notes |

| 50 | Fan | 46 | 1775 | Fan is likely Fanny. She is listed with her children, one of who has children of their own. Based on her age, she is inferred to be the daughter of Dinah. |

| 52 | Phillis* | 24 | 1797 | She is listed with two children: Eliza, 6, Kitty, 2. Neither of these children would have been born when the suit was brought forth in 1812, and are not likely to be listed in the original list of seventeen. Phyllis is named in the 1821 appeal for having a child in the interim and this could refer to Kitty born around 1819. In the case summary, Richard Burgess testified that all Dinah was mother or grandmother of all, except one which the witness believed was a female but her name he did not recollect” As Eliza was listed in the 1853 as a Wood, and John &c is named as a child of Fan and Phillis is listed prior to John in the list, it suggests that Phillis is John’s partner and not his sibling. [see below] |

| 51 | John | 23 | 1798 | John is likely the John Wood, age 55, named in the 1853 Robert D Sewall inventory [JH 2:699] who is listed between the family groups of Eliza and Kitta in the inventory. It is unclear from the 1821 inventory if John and Phyllis are siblings or partners. However, based on Burgess’s recollection it is likely they are partners. Since he is listed as a descendant of Dinah in the court case, therefore the grandson of Dinah. |

| 56 | Paul | 19 | 1802 | Based on his age and the fact he is listed below Fan, he is inferred to be the grandson of Dinah. Three Pauls appear in the 1853 Inventory, all born after the 1821 Inventory was compiled. One of the Pauls is the son of Charles and Suck. See more about this relationship in the row about “Suck”/Susannah. |

| 57 | Moses | 13 | 1808 | Based on his age and the fact he is listed below Fan, he is inferred to be the grandson of Dinah. He is likely the Moses named in the will of William H B Sewall, the son of Richard Sewall and the brother of Robert D. Sewall. William had inherited the St. Mary’s County properties from his father Robert Sewall upon his death in 1820 and the legal authority to enslave a portion of the people enslaved by the Sewalls. In his will dated 1824, he requested that Robert D Sewall “give my servant Moses his freedom when he arrives at the age of 23.” [St. Mary’s EJM 1:225] A Moses, 22, was included in Wm HB Sewall’s St. Mary’s County 1831 Tax Assessment. This is consistent with the age of Moses in the 1821 Inventory. In 1832, Robert D. Sewall fulfilled the request and registered Moses’ certificate of freedom in St. Mary’s County. As he was freed in 1832, it is not expected to find him in the 1853 inventory. |

| 56 | Suck | 17 | 1804 | Based on her age and the fact she is listed below Fan, she is inferred to be the granddaughter of Dinah. She is in the 1853 inventory as “Luck” and is grouped with Charles, her inferred partner, and their children. Among her children’s names are Paul, Susannah, Phillis, Dinah, John, Charles. All of these names occur in the list compiled for the court case. Death certificates for Susan’s children (who lived in Rosaryville after the Civil War and emancipation) name their parents as Charles Brown and Susan Wood. |

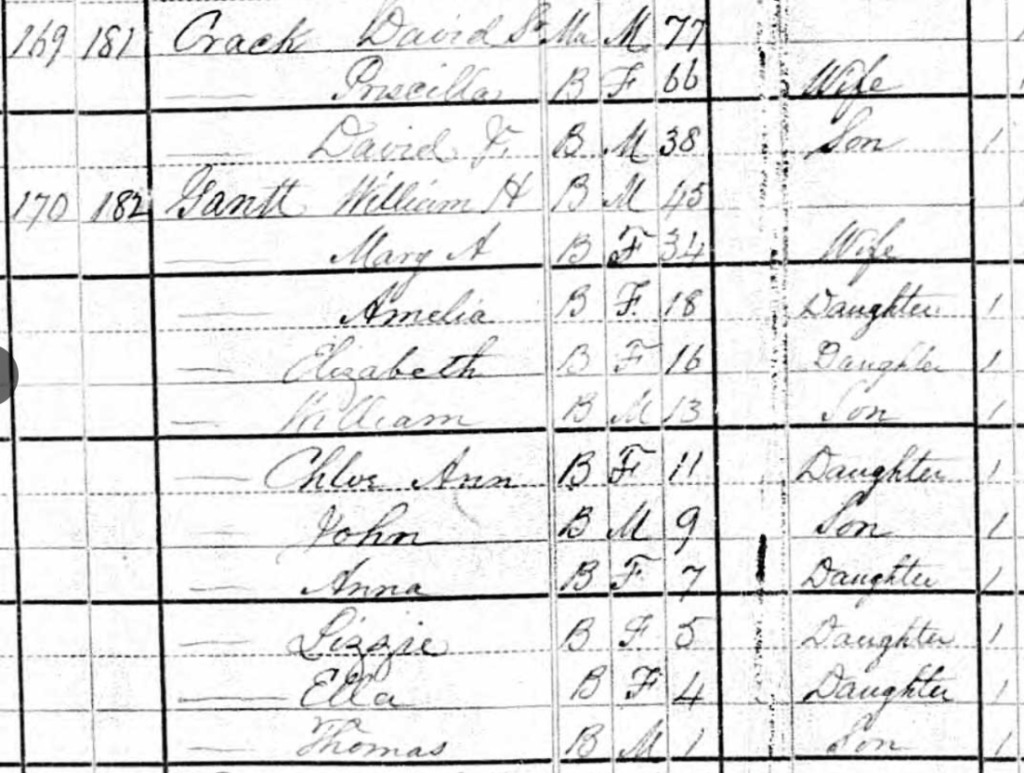

Pat & children (1 child + 3 grandchildren) [Brown]

| Inventory Line Number | Name | Age | Est BY | Notes |

| 59 | Pat | 42 | 1779 | Based on her age, she is inferred to be the daughter of Dinah. She is listed with Andrew, age 47, and who is not named in the list, suggesting that Andrew is Pat’s partner and not her sibling. In the 1821 inventory she is listed with children ranging from ages 1 to 18 [eight children total]. Of the children: Isaac, Kitty and Charles were born prior to 1812 and the start of the court case. Pat is named in the 1821 appeal for having a child in the interim and this could refer to her other children: Tom, Nancy, Milly, William and Nelly. Of these children, the names Tom, Nancy, and Nelly appear in the list, suggesting the familial relationship. She appears in the 1853 Inventory with her son, William. |

| 60 | Isaac | 18 | 1803 | Based on his age and the fact he is listed below Pat, he is inferred to be the grandson of Dinah. Isaac is likely the Isaac Brown, age 50, listed in the 1853 Robert D Sewall inventory. He is listed with an inferred partner, Sally Ann, and his children, among whom are Patsey, 20, Isaac, 19, Kitty, 11, Charles, 8, and Sam 6. These names correspond with the original list. |

| 62 | Charles | 11 | 1810 | Based on his age and the fact he is listed below Pat, he is inferred to be the grandson of Dinah. Charles does not appear to be listed in the 1853 inventory. Susannah “Suck” Wood, daughter of Pat, partnered with a Charles Brown and fathered many children. It is possible that she partnered with her first-cousin Charles, son of Pat. This has been ruled out due to the estimated birth years of both Charles. In 1821, Charles Brown, son of Pat, has an estimated birth year of 1810. In 1853, Charles, partner of Susannah, is listed as 54 years old, giving him an estimated birth years of 1799, a full decade earlier. His age in the 1853 inventory is consistent with the 1870 census which lists him as 75 and gives him an estimated birth year of 1795, ruling this Charles out as her partner. |

| 61 | Kitty | 15 | 1805 | Based on her age and the fact she is listed below Pat, she is inferred to be the granddaughter of Dinah. The five inferred children of Fan were listed immediately after Fan in the list provided by Berry and assumed to be copied in the same order as the primary source. However, Kit in the list, is not immediately after Charles, which suggests that it may be a different Kit/Kitty. |

Nelly (1 child)

| Inventory Line Number | Name | Age | Est BY | Notes |

| St Mary’s Inventory[TT 5:25] | Nelly | 30 | 1791 | Based on her age, she is inferred to be the daughter of Dinah. Like Moses, son of Fan, she appears to have been separated from her family and kept at the St. Mary’s County properties. She was listed with a child, Eliza, who would have been born after 1812 and prior to the 1818 judgment. She appears in Wm HB Sewall’s St. Mary’s County 1831 Tax Assessment; she is listed as 40, giving her the same estimated birth year of 1791. The assessment is sorted by age and so it is difficult to infer if she had additional children. |

Sally (1 child + 1 grandchild)

There are three Sal/Sal/Sale listed in the Inventory, all roughly the same age: 26, 29, 24.

| Inventory Line Number | Name | Age | Est BY | Notes |

| 19 | Sale | 24 | 1797 | She is listed as “Sale”, which makes her name the most phonetically similar to Sally, listed in the court case. However, where she is positioned in the 1821 inventory places her far away from the other children and grandchildren of Dinah. This suggests that is not the daughter of Dinah. |

| 68 | Sal | 29 | 1792 | She is listed amidst the other children and grandchildren of Dinah, heading a household that immediately follows Pat’s. This would lend circumstantial support that this is the correct “Sally” Additionally, she has two children: Hariot, age 9 and William, age 5. Sal is also named in the 1821 court case which suggests that William was born after the 1818 judgment, although his age of 5 suggests he was born before 1818. |

| St Mary’s Inventory[TT 5:25] | Sal | 26 | 1795 | Like Nelly and Moses, if this is the correct Sal, she would have been in St. Marys County. She is listed with her children immediately prior to Nelly, which suggests the relationship between the two as inferred sisters. Likewise, she is listed with three children: Tom, born 1811 and possibly named in the list, and two children born after 1818 (17 months and 3 weeks). The ages of the children align better with the details from the court case. Based on her age and the ages of her children, she is inferred to be the daughter of Dinah. |

The Brothers Clarke (3 children)

| Inventory Line Number | Name | Age | Est BY | Notes |

| 73 | John | 41 | 1780 | John Clarke “old” is listed in the 1853 Inventory after the Kitty (Wood) family group. He is listed without an age. Pat, his inferred sister, at 74 is listed as the oldest person in the inventory with a listed age. If “old” John Clarke is Pat’s brother, and the Capt John identified in the 1821 inventory, then he would have been born one year after Pat. The designation of Capt would indicate that he was trained as a carpenter. |

| 72 | Sampson | 37 | 1784 | After Sal, the inventory lists 4 adult males: Tom, Sampson, Capt John, and Capt George. These names [John, Sampson, Tom] occur in the same sequence and what we have seen is that the list of people mostly mirrors the list in the 1821 inventory. |

| 71 | Tom | 32 | 1789 | Thomas Clarke is listed in the 1853 Inventory near the start, between other identified Clarke children. He is listed as 70 (which may be an estimation of his old age). In the 1821 Inventory he is listed with his brothers away from his partner and children, as was typical of plantations. The 1853 inventory lists him with partner Charity, allowing us to infer that his partner and children are listed in the 1821 inventory, albeit in a different section [Line Number 90-93]. This places them as the second family group after Dinah the matriarch. |

Nancy [deceased] ( + grandchildren)

[Nancy], Kit, Anna, Harriott “Harriott is the daughter of Nancy, who is deceased”

Nancy does not appear in the 1821 inventory and it is unclear if Anna or Harriot are listed. A Harriot is listed as 9 years old who is the daughter of Sal, who was previously discussed and set aside as the Sal mentioned in the courtcase. However, she is listed between Fan and Pat (and their offspring) before the Brothers Clarke and their inferred wives and offspring. This suggests that Ann and Sal may be the same, as Sally Ann is a common combination.

If “Isaac, Nancy &c are the children of Patt”, this would suggest Sal/Ann took in Harriott after Nancy died. Without further documentation it is speculation.