Connected Post: Richard (Dick) Jones & Mary (Polly) Jones | Old Age

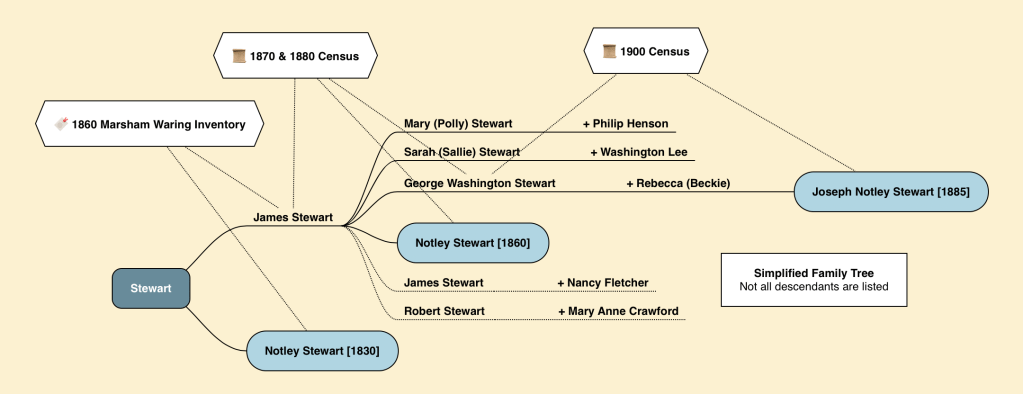

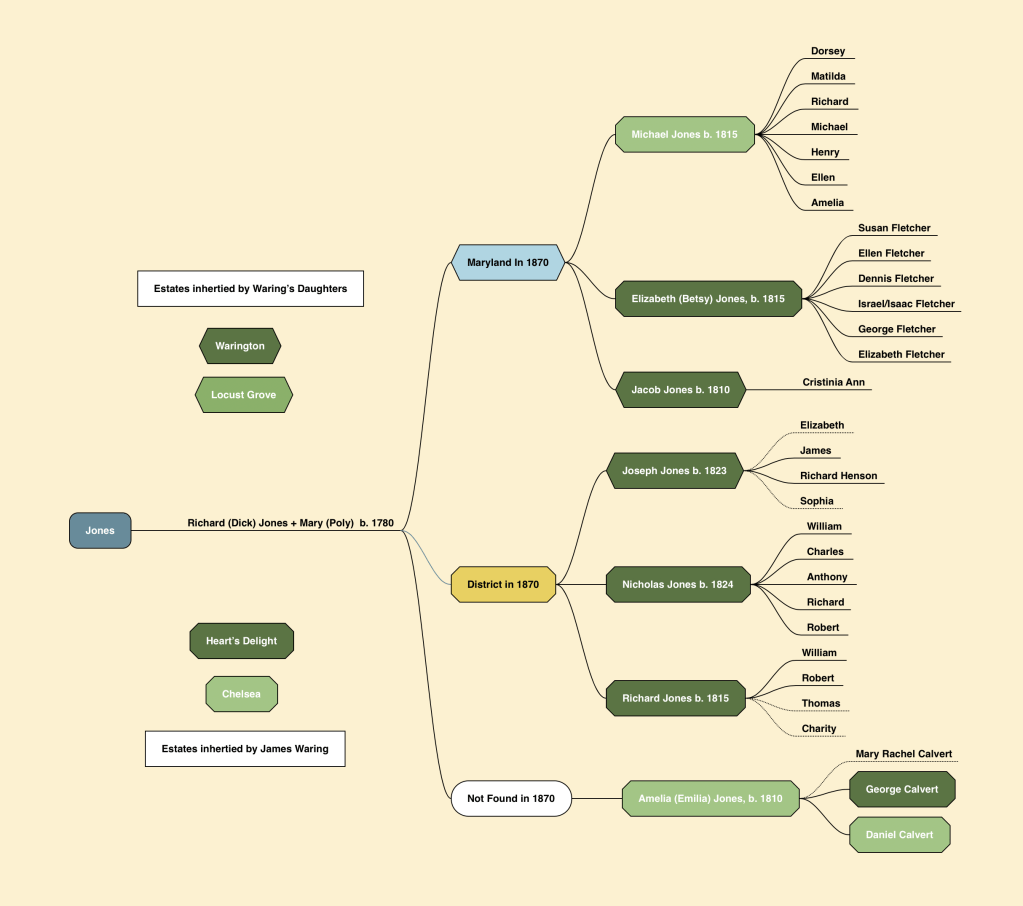

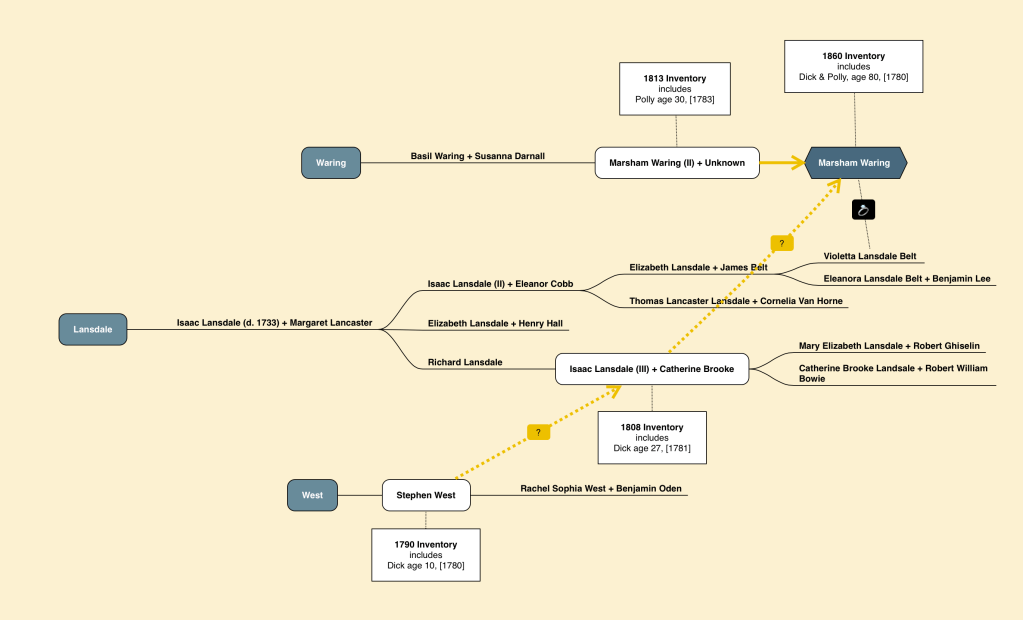

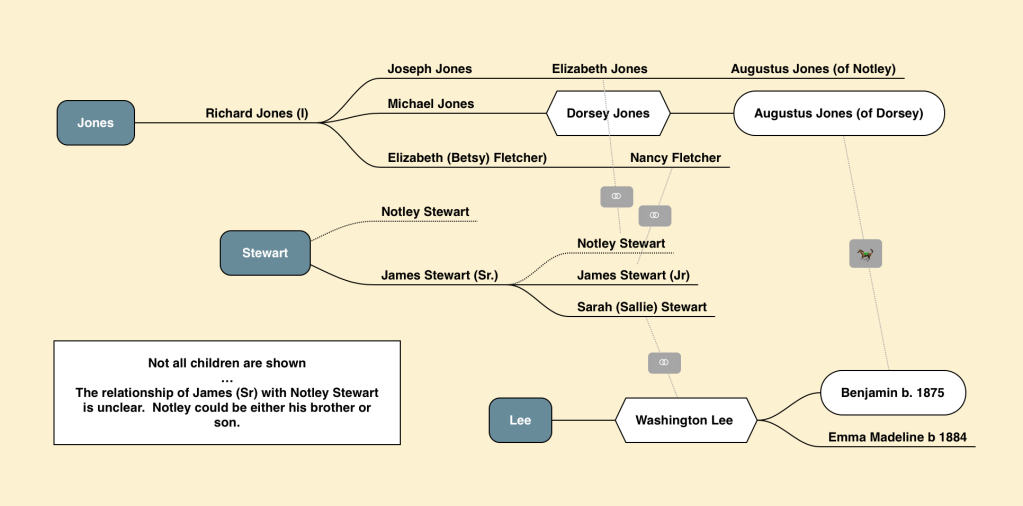

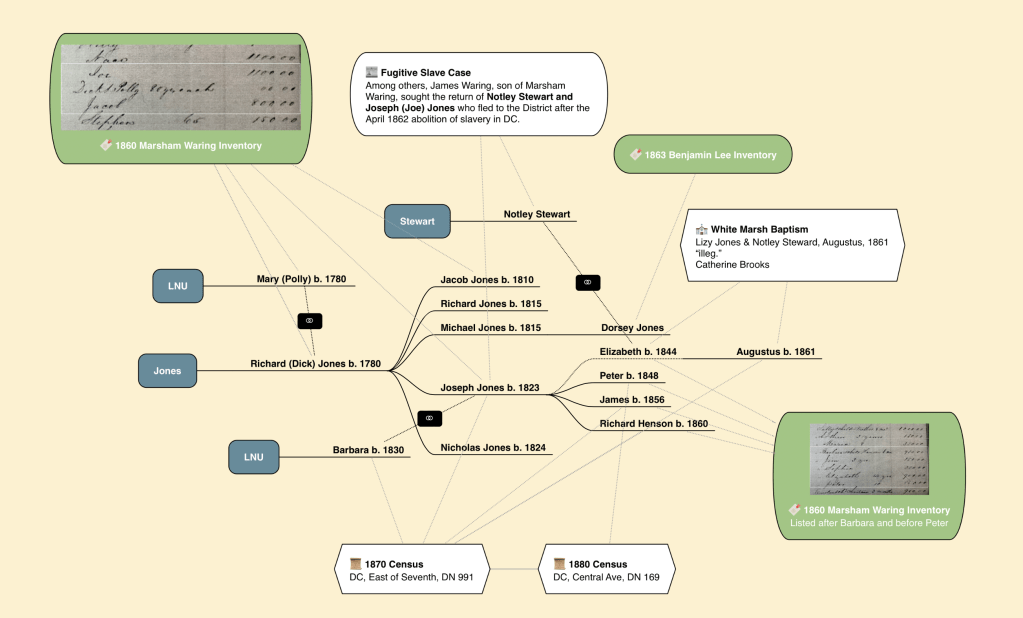

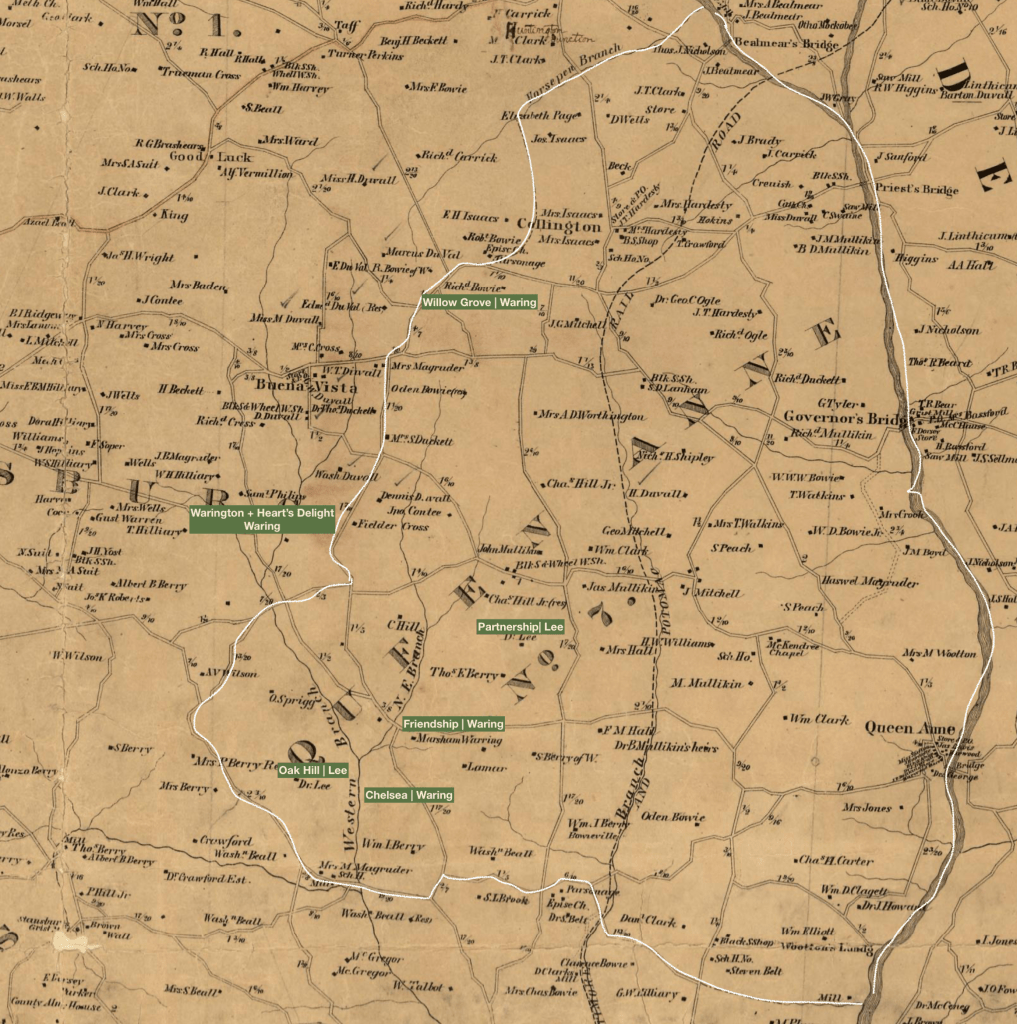

Richard (Dick) Jones and his wife, Mary (Polly) were born at the end of the Revolutionary War and lived until the start of the Civil War in Queen Anne District of Prince George’s County. The vast majority of their life was spent on the estates of Marsham Waring. They and their children labored for Waring and his three children, as well as neighboring estates. This post explores the life of one of their sons, Nicholas Jones.

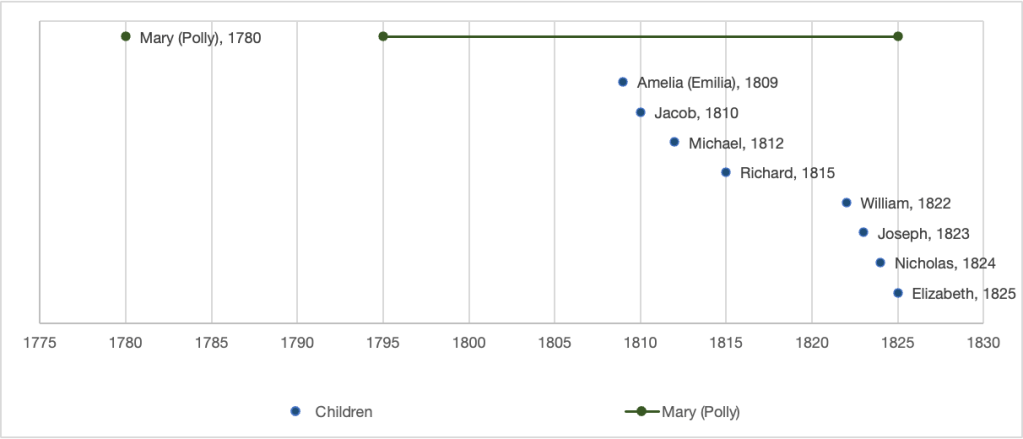

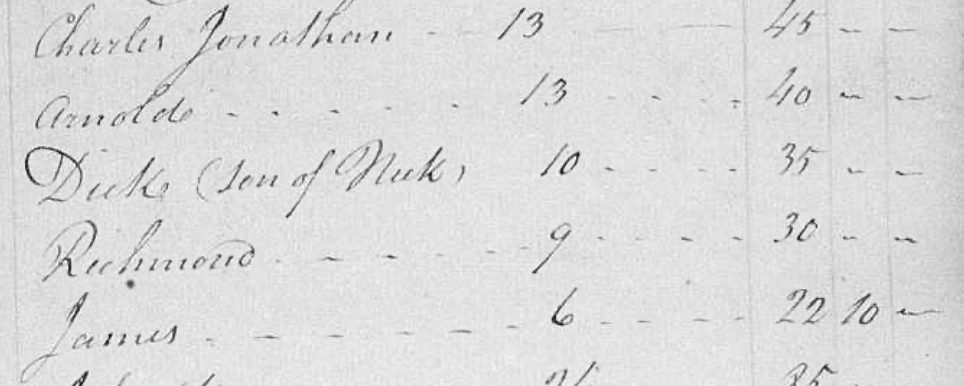

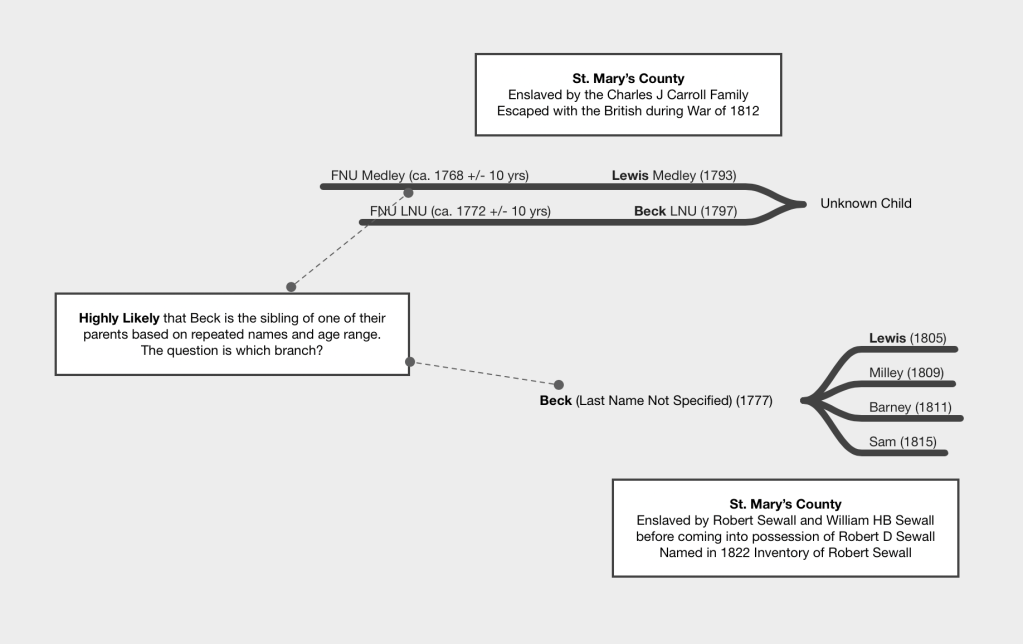

Nicholas Jones was one of the younger sons of Richard and Mary born toward the end of Mary’s estimated child-bearing years (1795-1825), when she was 15 to 45 years old. If my theory is correct about Richard’s forced migration from Stephen West to Marsham Waring (see connected post), then Nicholas was named after his grandfather, Nick.

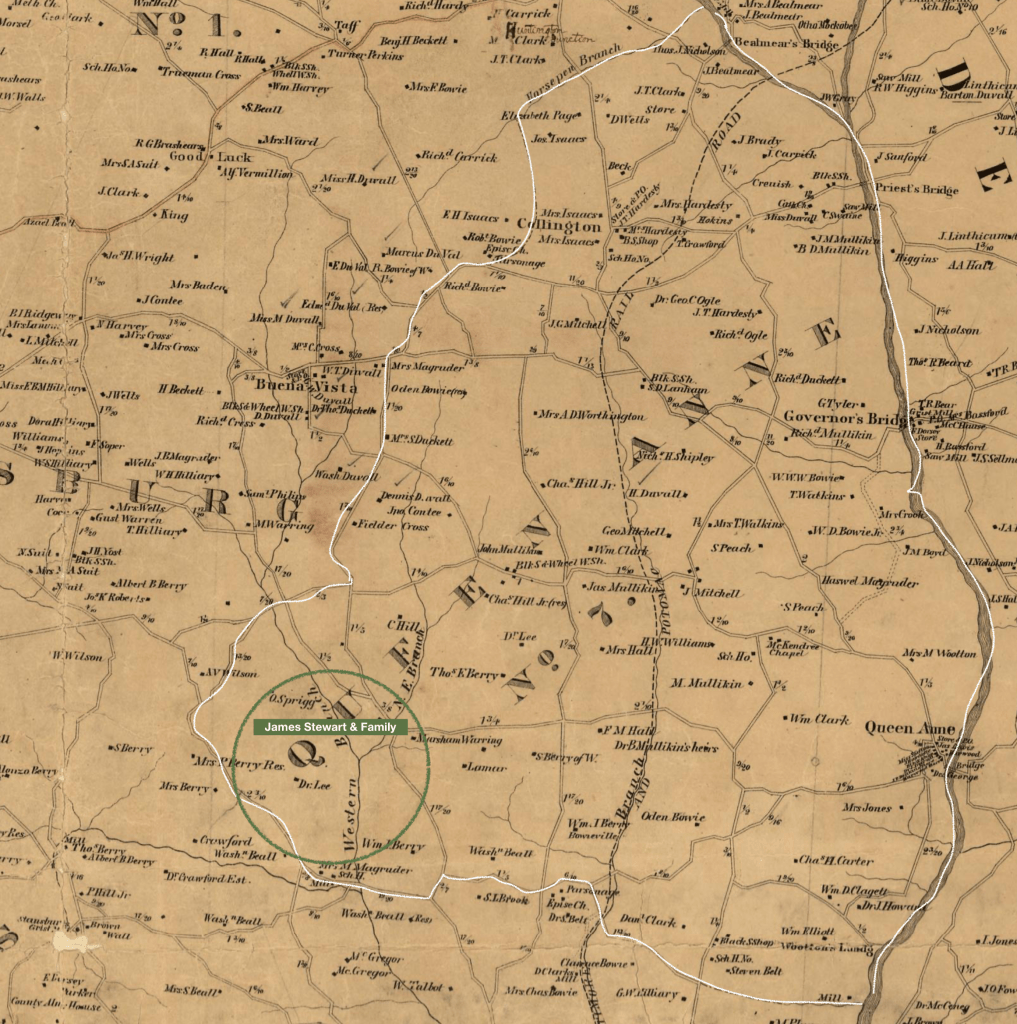

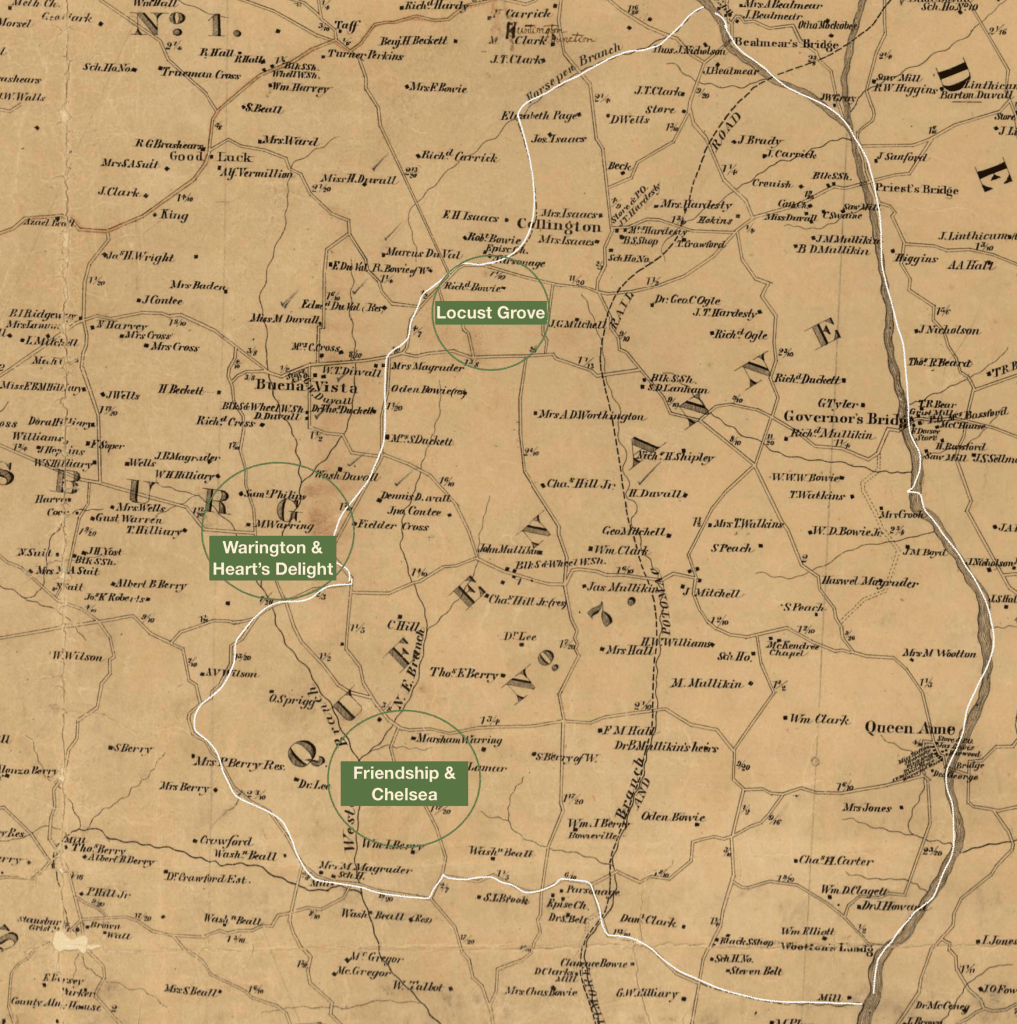

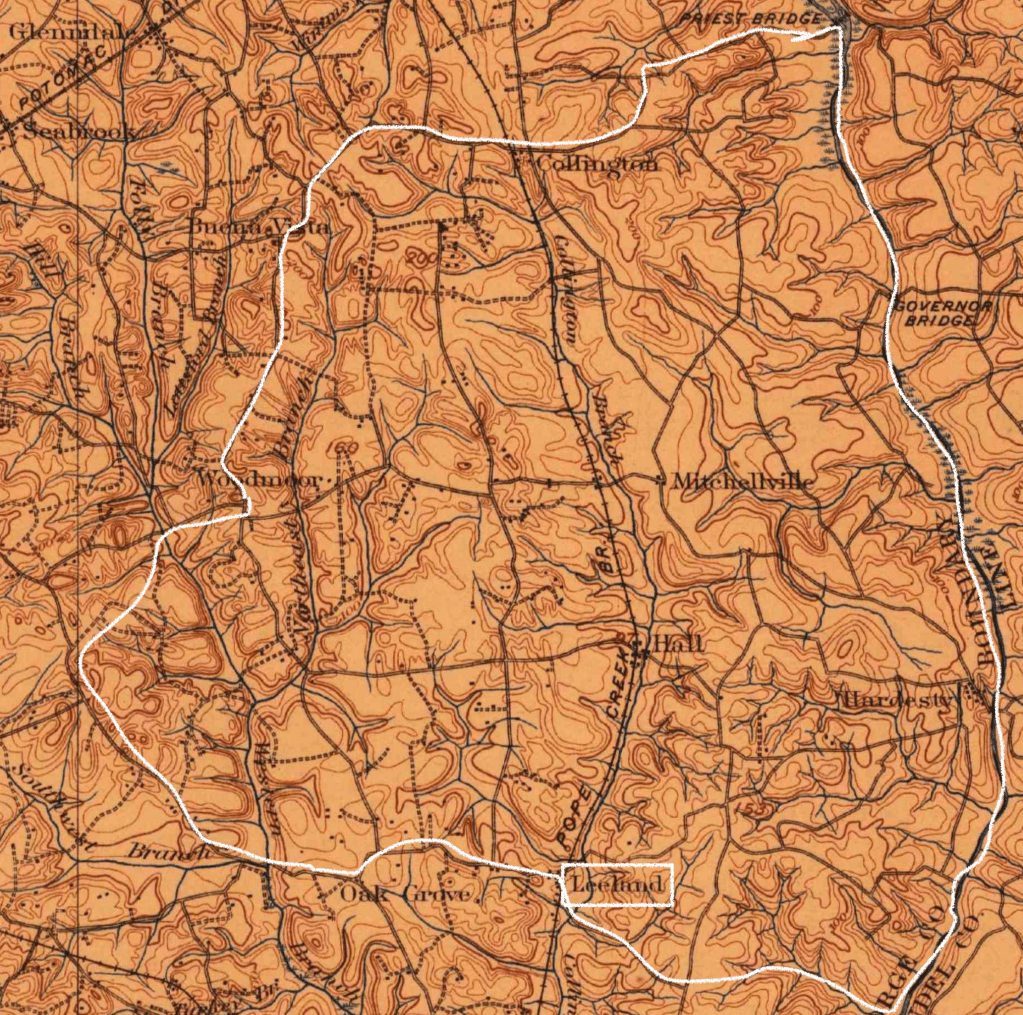

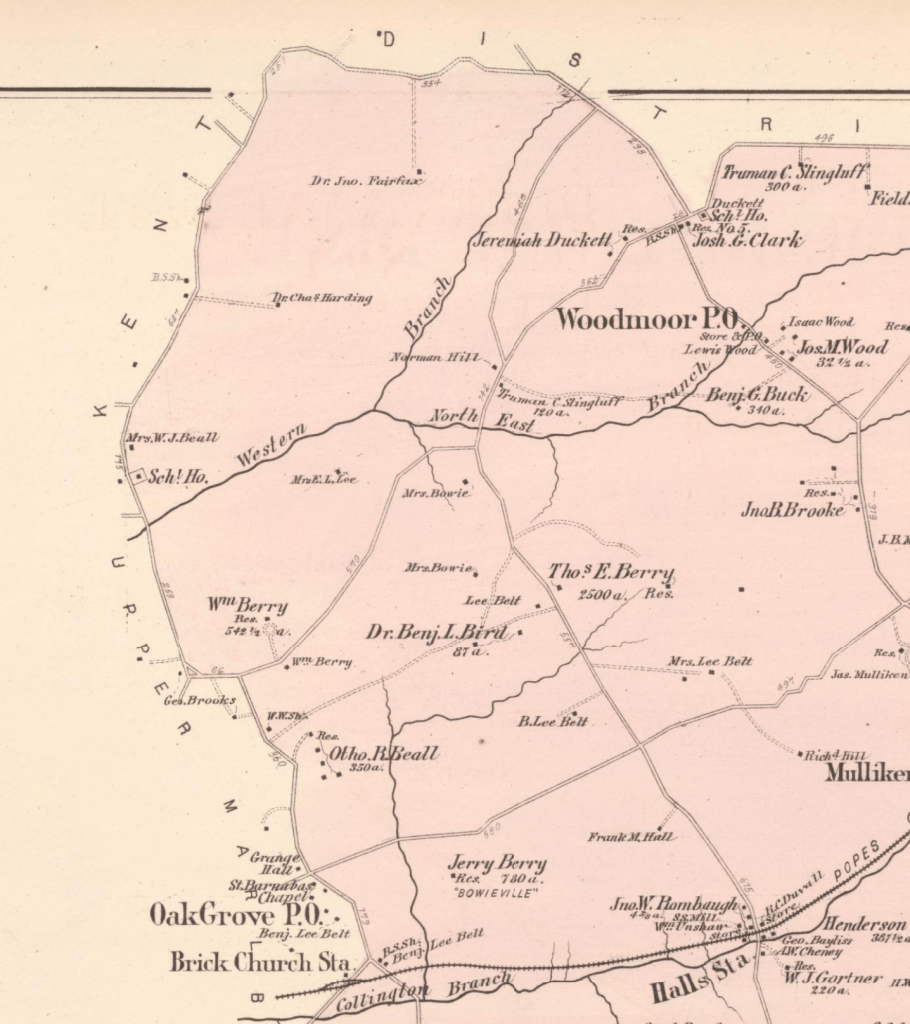

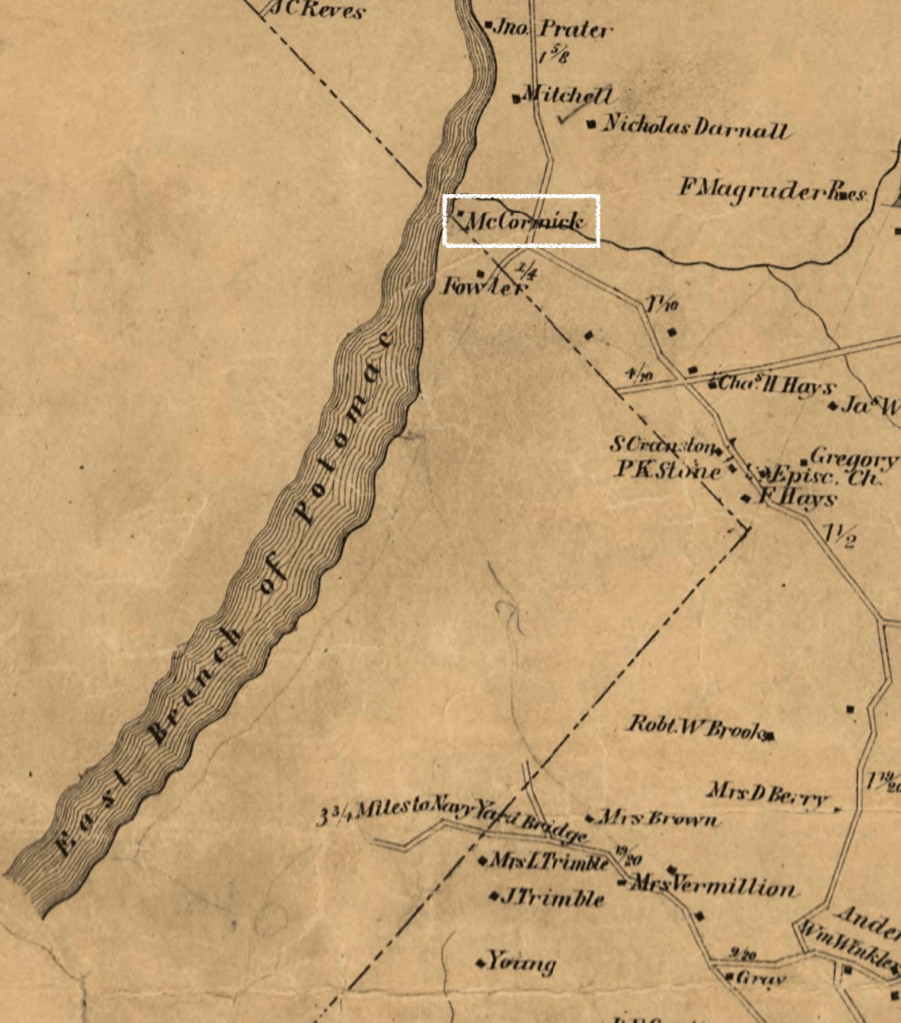

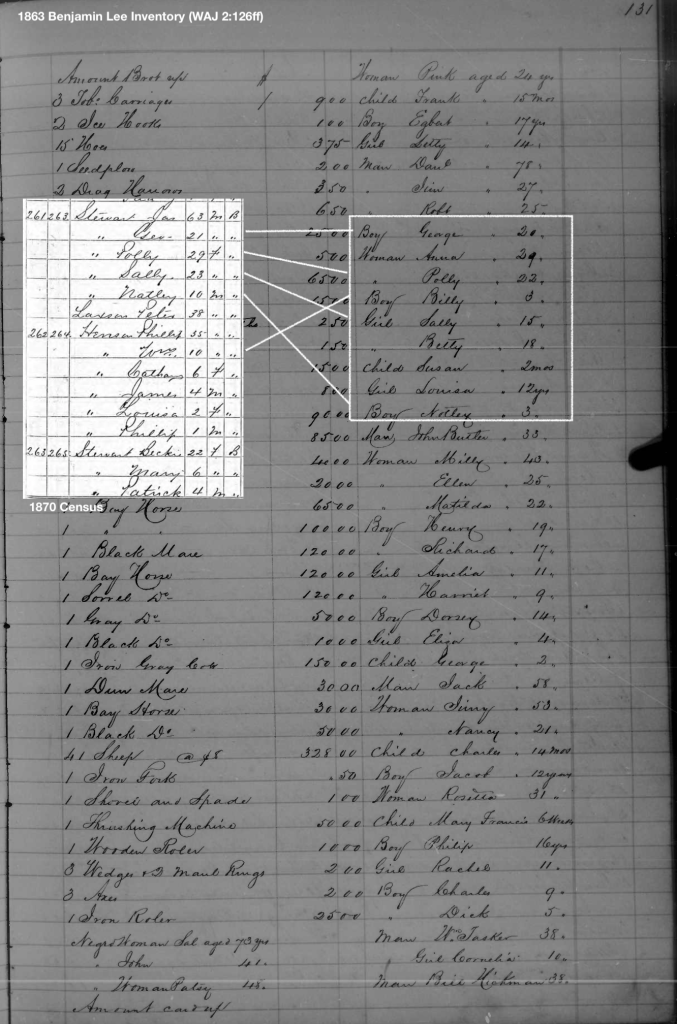

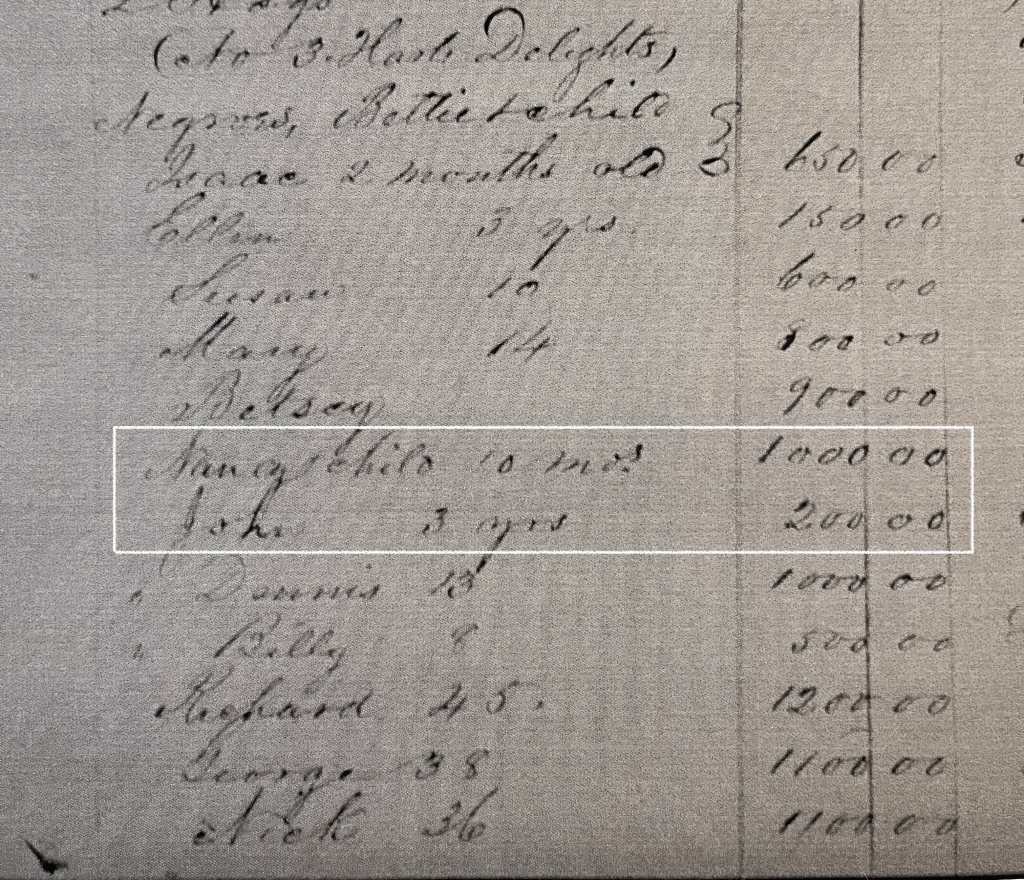

He labored on the Waring estate “Heart’s Delight”, which was in Bladensburg District near Buena Vista, near the Warington estate where his parents lived and labored. His wife and children labored on a neighboring estate owned by John B Magruder.

Nicholas and Martha had several of their children baptized by the priests of White Marsh.

- 1853: Richard Euseb., son of Nichol. [Johns] & [?] Williams, property of J. Magruder; Sponsor: Chas. Gasebeth

- 1856: Robert, son of Nichol [John] + Martha Williams, property of John Magruder; Sponsor: Thomas Allen

- 1858: Lucy, of Nic Jones & Martha Anne, property of J. Magruder; Sponsor: Susan

- 1862: Nicholas, of Martha & Nich Jones, col.; Sponsor: Carolina Green

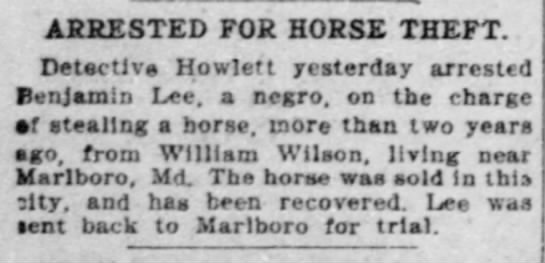

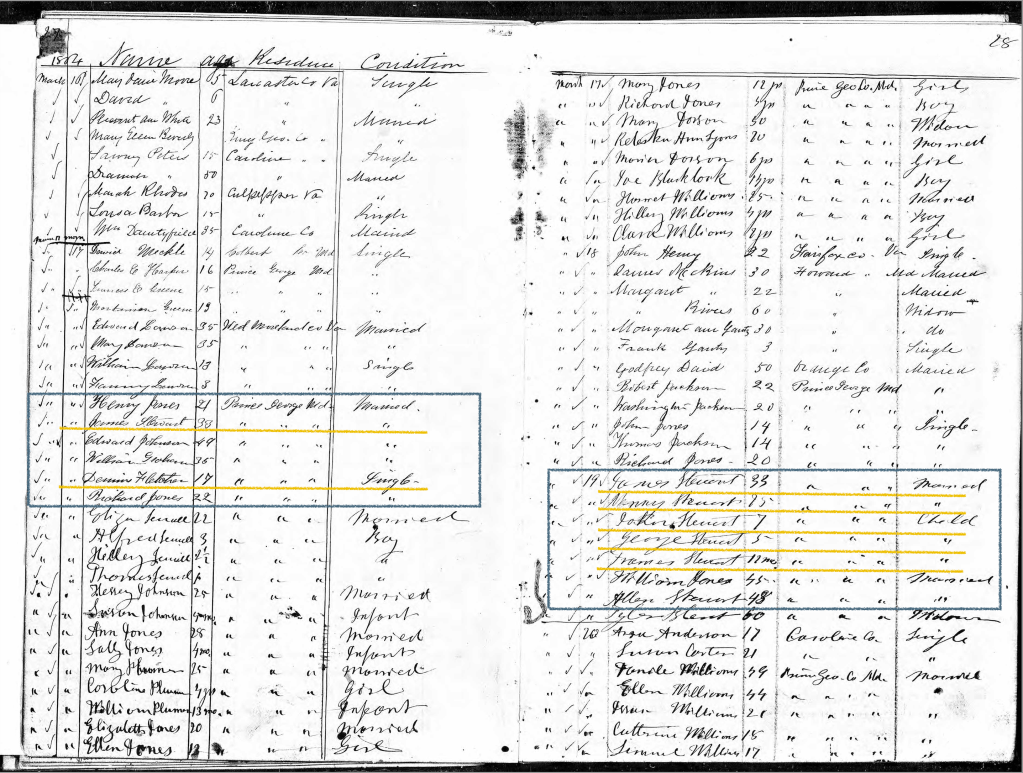

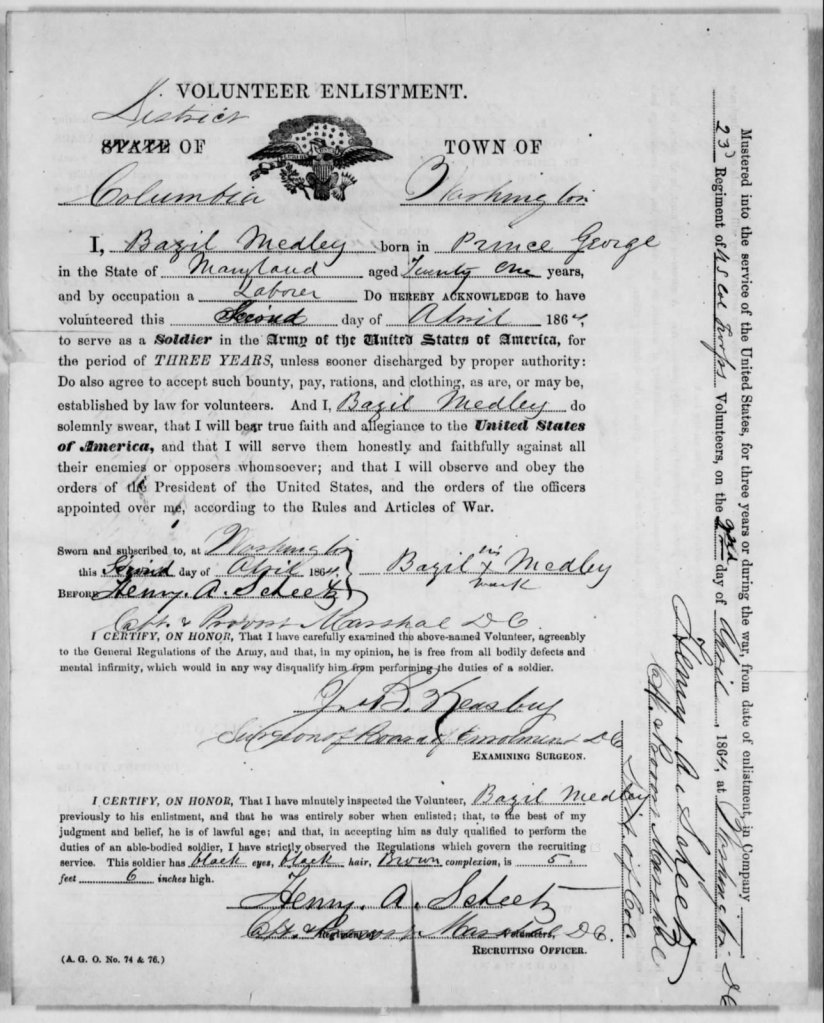

In May 1862, a group of enslaved people from Waring’s estates fled to DC with James Waring, Marsham’s son, pursuing them. He swore out an affidavit, swearing that they were enslaved in Maryland, not the District, and therefore he was lawfully able to seek their return to bondage. Some of those named in the affidavit were Nicholas’s siblings, Joseph and Richard. Nicholas was not named, however, he is living in the District in the 1870 Census, suggesting he joined them later.

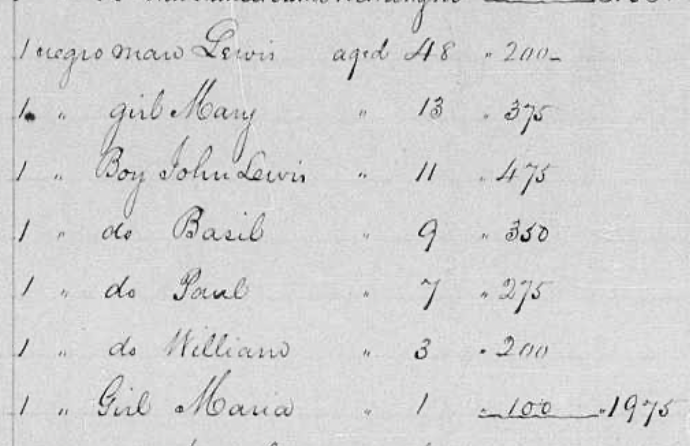

In 1864, Martha and her children are listed in the Freedmen Bureau’s Registration list for Camp Springdale, without Nicholas, her husband. She was recorded as Jones, and some of her children were recorded as Johnson. A comparison of the lists of names in the Freedmen’s Bureau Record with that of John B Magruder’s list of enslaved people he submitted to the Prince George’s Commission on Slave Statistics for compensation however show similar given names and ages and is similar to the list of names found in the White Marsh baptismal records. Again, Martha’s husband, Nicholas Jones is not listed with them.

—

Prince George’s County Slave Statistics Original Scans | Maryland State Archives

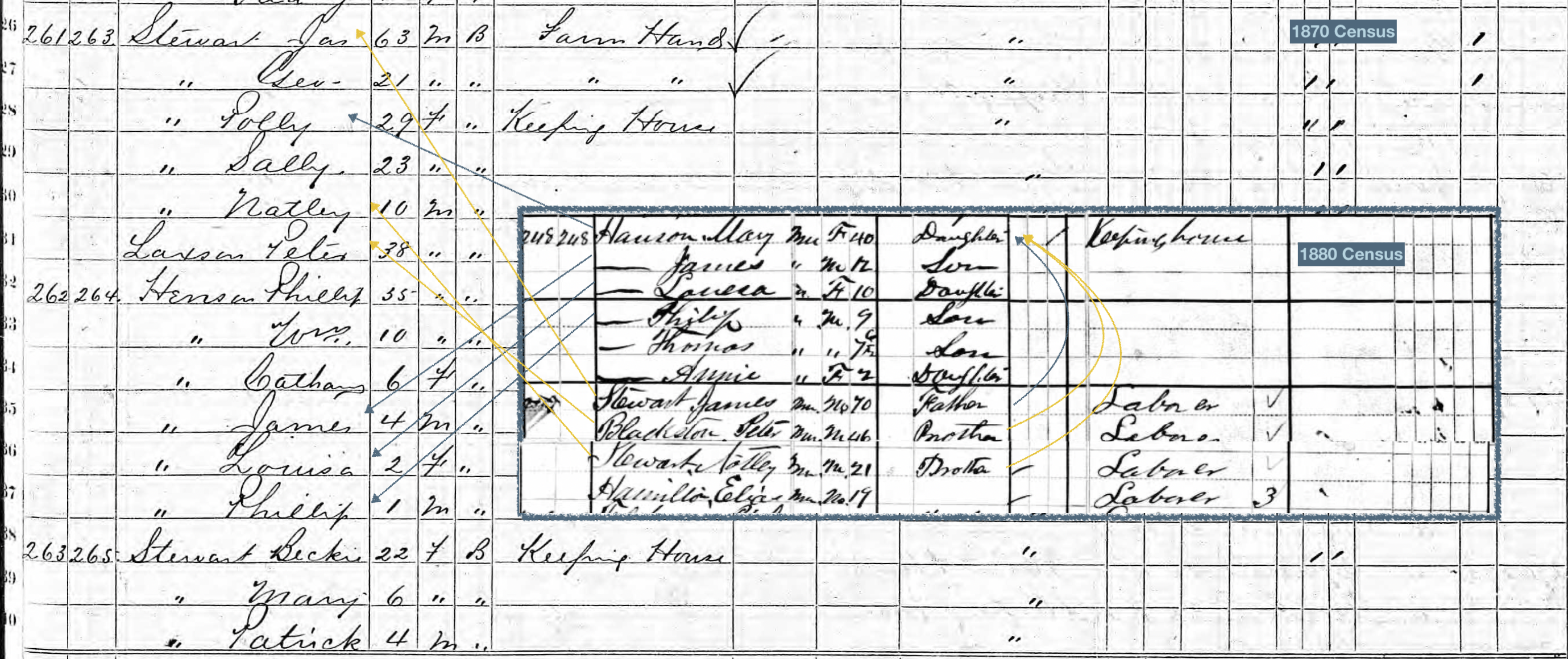

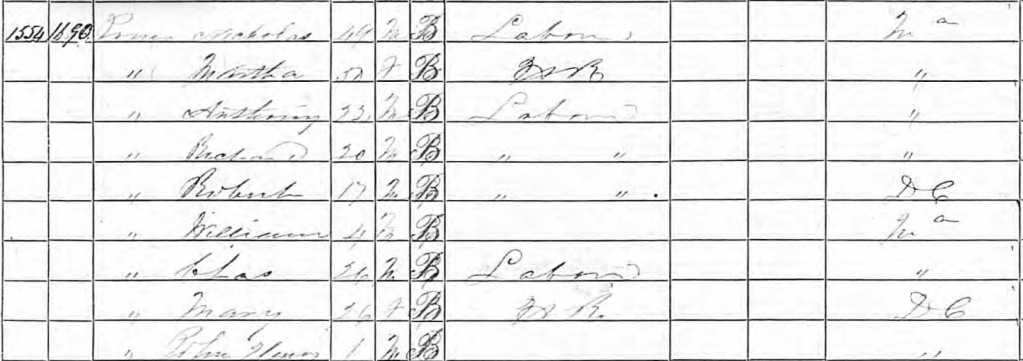

They are reunited by the 1870 Census. Nicholas and his wife lived with four of their sons; one of their sons, Charles, had married and his wife and children lived with them in the District. They worked as laborers. How and where they labored is unclear.

They lived near D & 13th NE on the far edge of town, near the boundary with the county and along the road to Benning’s Bridge. Other siblings were found in the County near Benning’s Bridge in the 1870 and 1880 census records.

By October 1870, Martha, Nicholas’ wife had died of consumption, now more commonly called tuberculosis.

After 1870, the lives of Nicholas and his children become obscured. Other than Nicholas consistently living in Ward 6, the family and its members are not reliably identified in the 1880 census records. A widowed Nicholas Jones is identified in the census, living on B Street SE, which would suggest it is the same Nicholas Jones. He is recorded as born in Virginia, though this could have been an error made by the census enumerator, as other senior members of the household are also listed as born in Virginia.

He is in the household of Frances Williams and her grown children; this suggests he moved in with one of his wife’s relatives, if this is the same Nicholas Jones.

A death record for 1899 lists Nicholas Jones, widowed, who was born around 1815. He was buried at Potter’s Field, part of the Washington Asylum, the “poor house”. It was located near where Nicholas Jones was recorded living in the City Directories.